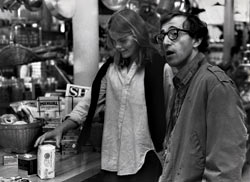

Manhattan is not just Woody Allen’s dream movie. Wistful as it is witty, it’s his dream of the movies. Forty-four when he made Manhattan (1979), Allen was never more vividly himself than as the self-absorbed, Nazi-obsessed, horny TV writer and babe magnet Isaac. Whether or not Manhattan is Allen’s most personal movie, it enshrines everything from his morality to his milieu. The opening, a Gershwin-scored skyline montage, segues naturally to a table at Elaine’s. Solipsism reigns supreme. No less than Quentin Tarantino, Allen can be the sum of his references; this is the movie where he offers his checklist of what makes life worth living, beginning with Groucho Marx. You are what you dig. Manhattan is the movie where Allen successfully projected his own self-absorption as a universal condition—and people responded with their personal identity politics. What’s most authentic about Manhattan is its fantasy. The 1977 New York City that Woody so tediously defended in Annie Hall was in crisis. And so he imagined an improved version. More than that, he cast this shining city in the form of those movies that he might have seen as a child in Coney Island—freeing the visions that he sensed to be locked up in the silver screen. In a way, Manhattan is Allen’s personal Purple Rose of Cairo—the movie in which he successfully projects himself into Hollywood make-believe.

Manhattan: Woody Allen Shags a Teenager!