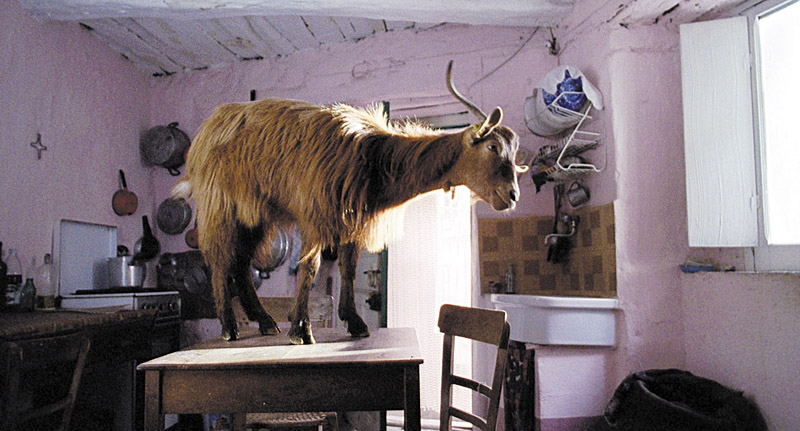

Grave, beautiful, austerely comic, and casually metempsychotic, Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte is one of the wiggiest nature documentaries—or almost-documentaries—ever made. Frammartino’s second movie is virtually without dialogue, yet filled with the sounds of the world and intensely communicative. The movie’s title translates to “The Four Times,” but, not simply seasonal, it projects four states of being: human, animal, vegetable, and mineral. Le Quattro Volte begins with a wheezing old man and his herd of goats emerging out of the smoke rising from a charcoal kiln; the movie ends with the charcoal haze of what was once a mighty fir drifting across the screen. In between, the goatherd gathers dust from the floor of the village church, which he mixes in water and drinks each night as a medicinal elixir. It evidently works—the morning after he misplaces his daily packet of church sweepings, he dies. The moment is stunningly casual. Le Quattro Volte is a movie in which animals have at least as much presence as humans. The goatherd’s persistent cough merges with the clamor of his herds’ conversational “baa”s and tinkling bells. Man has been displaced from the center of the world, but, if one follows the filmmaker’s logic, his soul migrates first into a newborn kid and then, once the kid is separated from the herd and lost in the snowy forest, into the sheltering tree that becomes the movie’s ultimate protagonist.

Le Quattro Volte: Deep Into the Soul of Italy