Last weekend, as Jerry Bruckheimer’s pirates were once again storming the international box office, the Cannes Film Festival (May 16–27) bestowed its two top prizes on a gut-wrenching Romanian movie about backroom abortion and a plaintive Japanese drama about a sad old man who wants to dig his own grave. In addition, there were awards for a two-and-a-half-hour study of marital infidelity in a Mexican Mennonite community, and for a zigzagging, border-crossing Turkish-German production that begins as the story of an old man’s lust for a middle-aged prostitute and ends up charting the lesbian affair between a Hamburg college student and an Istanbul revolutionary.

What all of those films have in common—aside from the fact that none seems in danger of an imminent Hollywood remake—is that they will soon open commercially in French cinemas. On this side of the Atlantic, they may be coming sooner to a living room near you.

Miraculously, the best of the lot, Romanian director Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, was bought by the adventurous American distributor IFC Films even before it received Cannes’ prestigious Palme d’Or from a jury headed by The Queen director Stephen Frears. A release date hasn’t been determined yet, but 4 Months will roll out as part of IFC’s ongoing “First Take” program, which opens movies in a handful of theaters on the same day it makes them available for purchase via on-demand cable television. Last year’s Palme d’Or winner, Ken Loach’s excellent The Wind That Shakes the Barley, was released in the same manner and even became a modest hit. Still, I’d wager that Mungiu didn’t come to Cannes hoping for his film—with its stunning, handheld widescreen camera work—to make a beeline from the Grand Théâtre Lumière straight to America’s TiVos.

These days, though, any foreign picture that doesn’t star some gamine French ingenue or an Asian martial-arts hero is lucky to get a U.S. release at all. So, as the world’s most important film festival celebrated its 60th birthday, it was tough to shake the feeling that Cannes—or maybe France in general—has become an illusory oasis in an industry where the voice of art too rarely rises above the din of commerce.

Take, for example, this year’s winner of the Grand Jury Prize (commonly considered Cannes’ runner-up award, after the Palme): The Mourning Forest. Set in a rural retirement home where an elderly widower yearns to be reunited with his late wife, this reserved, haiku-like movie, composed of a few terse dramatic scenes and many others of wind blowing against trees and grass, is the latest feature by Japanese director Naomi Kawase, who, at age 38, is already a Cannes veteran. In 1997, her debut feature, Suzaku, won the Camera d’Or prize for best first film, and in 2003 she returned to the festival with her third feature, Shara.

Thanks to Cannes’ support, Kawase’s work has been distributed in France and is now even produced with the aid of French funding. In the rest of the world, including North America, she is virtually unknown, which may partly explain why The Mourning Forest received a considerably more enthusiastic reception from French critics than from their international colleagues, many of whom filed out of the late-evening press screening before the end of the film’s brief (97 minutes) running time. (Among those who stayed, several—including one critic assigned to review the film for a prominent Hollywood trade publication—were reportedly lulled into a deep slumber.) After catching up with The Mourning Forest the next day at the more reasonable lunchtime hour, I found myself of two minds about it. It is a film marked by lovely moments that falls short of the lyrical heights to which it aspires.

Hollywood was hardly absent from Cannes in 2007, though it sometimes spoke with a foreign accent. Five American films (including Zodiac and Quentin Tarantino’s Grindhouse-liberated Death Proof) were featured in the festival’s official competition, in addition to which there was My Blueberry Nights, a wan Jude Law–Natalie Portman romance shot in New York, Memphis, and Las Vegas by the Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai, and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, a flamboyant, French-language biopic directed by the American painter Julian Schnabel. Meanwhile, the iconoclastic New York indie filmmaker Abel Ferrara went to Italy to make Go Go Tales and came back with one of his best films, its story of a ne’er-do-well club owner (Willem Dafoe) on the verge of bankruptcy serving as an endearing metaphor for Ferrara’s own long career working outside of the studio system.

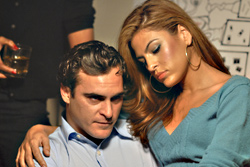

When Diving Bell opens in the U.S., it will have subtitles. But the Cannes competition film most in need of translation may be We Own the Night, a turgid and overwrought cop thriller from American writer-director James Gray, whose first two features (Little Odessa and The Yards) did little to impress U.S. critics or audiences but have inexplicably turned Gray into a Gallic fetish object. Last year, when We Own the Night (which stars and was produced by Yards alumni Mark Wahlberg and Joaquin Phoenix) was still in the editing room, one French critic I know made a special pilgrimage to L.A. to interview Gray and see a rough cut of the film. This year in Cannes, another French critic whose opinion I generally respect raved to me about Gray’s “classicism” while reminding me that, ever since the 1950s, the French have played an important role in championing great American directors whose work is insufficiently appreciated in America. “Why would we start to be wrong now?” he asked rhetorically. Well, there’s always a first time for everything.

One thing everyone (more or less) could agree on was that the Coen brothers, after floundering with Intolerable Cruelty and The Ladykillers, made a striking return to form with No Country for Old Men, a stark modern-day Western based on the Cormac McCarthy novel and featuring Javier Bardem as the creepiest movie psycho this side of Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs.

Also scoring high marks (and a special 60th anniversary prize from the jury, “for his career and because he made a lovely film”) was Gus Van Sant, whose Paranoid Park continues his recent string of low-budget films made with mostly unknown actors in and around his native Portland. Here, though, working from a source novel by Blake Nelson about a high-school skateboarder trying to make sense of his involvement in an accidental murder, Van Sant carries his ongoing experiments with image and sound design to new levels of sophistication. (The cameraman is the brilliant Christopher Doyle.) The result is a fragmentary, dreamlike portrait of teen alienation—the movie Van Sant was trying to make with Elephant—in which every artistic decision seems to flow organically out of the material rather than being lacquered on top (à la Schnabel). Van Sant is now fully unrecognizable as the director who once guided a slick Hollywood package called Good Will Hunting to massive box-office returns and nine Oscar nominations. No wonder that, by the end of Cannes, Paranoid Park had yet to find a U.S. distributor. (As this article was going to press, Variety announced that IFC First Take had once again come to the rescue.) Even less surprising is the news that Van Sant’s latest was fully financed by—you guessed it—the French.