James Whale was a debonair, openly gay British director who went to Hollywood from the London stage in the ’40s to make “art”; instead, his greatest successes were his monster movies, Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein. Adapted from Christopher Bram’s novel Father of Frankenstein, Gods and Monsters is a speculation on James Whale’s final days, a work of fiction grounded in fact.

The setting is Santa Barbara in 1957, more than a decade after Whale’s retirement. Ian McKellan’s Whale is a silver-haired effete who speaks in an upper-class lilt both seductive and sarcastic. A stroke has left him with a degenerative disease of the mind; shards of memory stab through his consciousness like flashes of monster-movie lightning. Between his failing health and the “electrical storms in his head,” as he describes it, Whale is more terrified of losing control than of dying.

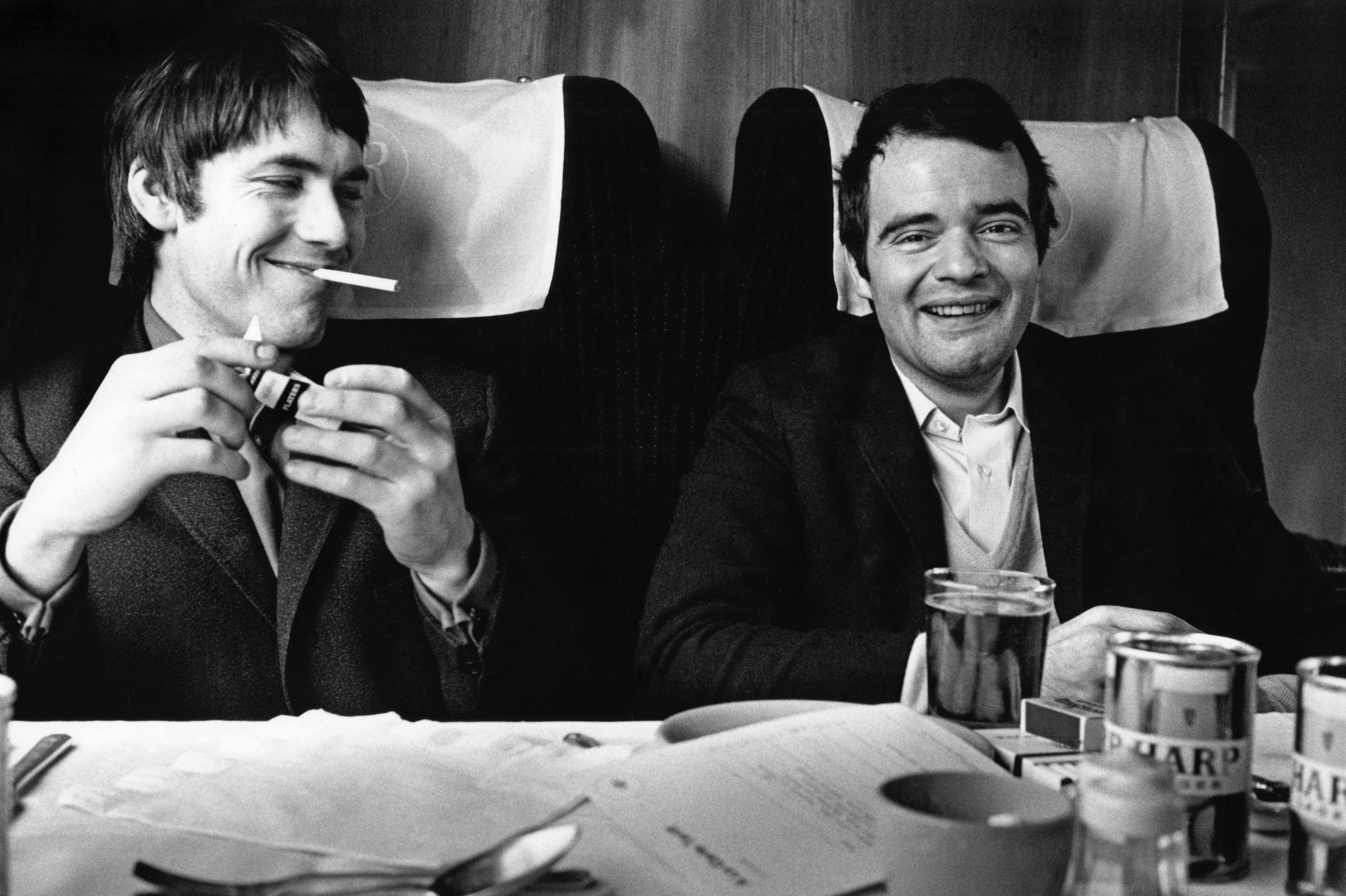

Rattling around his villa and cared for by his Hungarian maid, Hannah (Lynn Redgrave clucking and growling through a severe accent), Whale perks up at the sight of his shirtless young gardener, Clay (Brendan Fraser). After inviting the ing鮵e into his studio for a drink, Whale cajoles him into posing for him. “I have no interest in your body, Mr. Boone, I assure you,” he pleads with mock sincerity. Despite their differences, the British sophisticate and the guileless working-class American kid become friends.

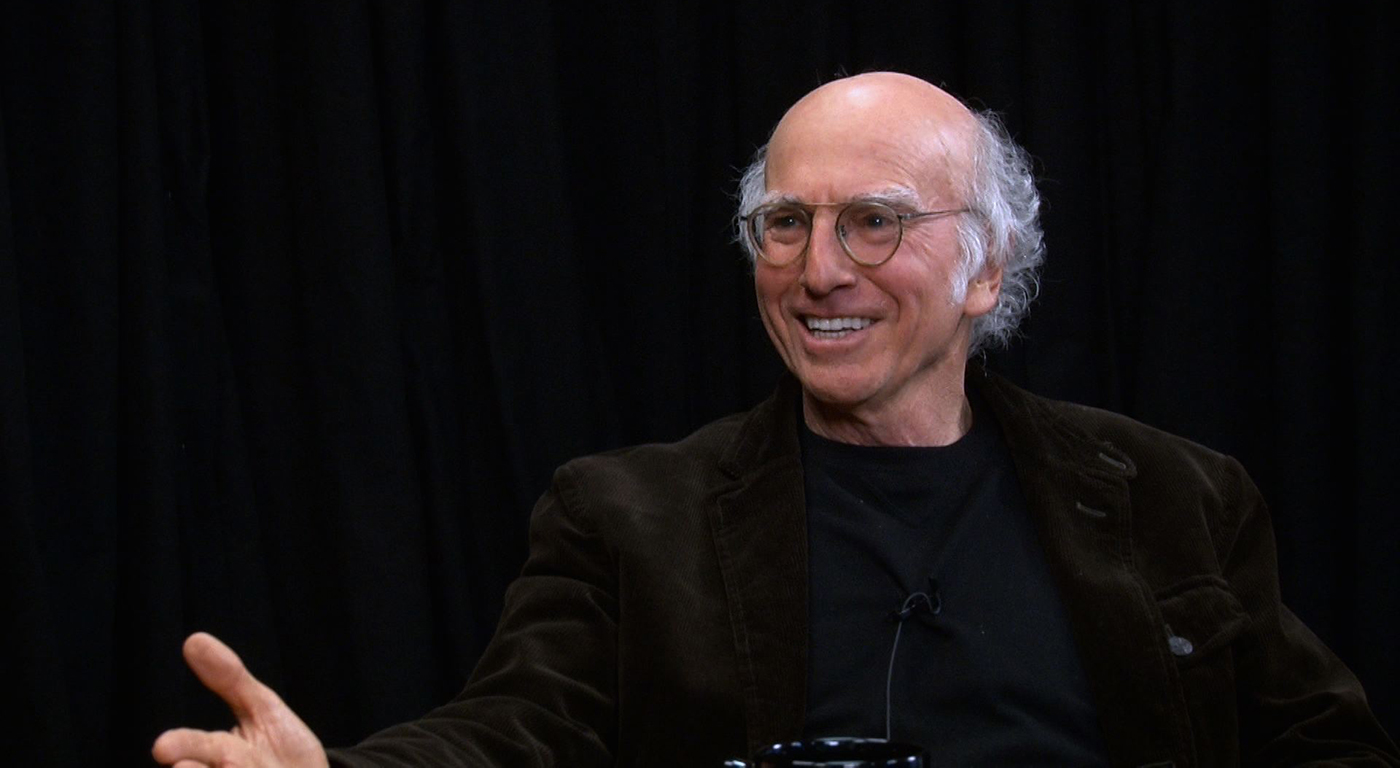

McKellan delivers an Oscar-caliber performance, allowing glimpses of Whale’s pain and fear behind his facade of easy charm and barbed wit. Fraser’s natural performance perfectly contrasts with McKellan’s theatricality. As Whale gradually comes to terms with what he remembers about the trenches of World War I, his stifling childhood, and his dubious achievements as a Hollywood director, the film turns into a richly realized evocation of a man struggling with inner demons. This is clearly a labor of love for director Bill Condon; with Gods and Monsters he remakes his otherwise unremarkable career.*

James Whale was a debonair, openly gay British director who went to Hollywood from the London stage in the ’40s to make “art”; instead, his greatest successes were his monster movies, Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein. Adapted from Christopher Bram’s novel Father of Frankenstein, Gods and Monsters is a speculation on James Whale’s final days, a work of fiction grounded in fact.

The setting is Santa Barbara in 1957, more than a decade after Whale’s retirement. Ian McKellan’s Whale is a silver-haired effete who speaks in an upper-class lilt both seductive and sarcastic. A stroke has left him with a degenerative disease of the mind; shards of memory stab through his consciousness like flashes of monster-movie lightning. Between his failing health and the “electrical storms in his head,” as he describes it, Whale is more terrified of losing control than of dying.

Rattling around his villa and cared for by his Hungarian maid, Hannah (Lynn Redgrave clucking and growling through a severe accent), Whale perks up at the sight of his shirtless young gardener, Clay (Brendan Fraser). After inviting the ing鮵e into his studio for a drink, Whale cajoles him into posing for him. “I have no interest in your body, Mr. Boone, I assure you,” he pleads with mock sincerity. Despite their differences, the British sophisticate and the guileless working-class American kid become friends.

McKellan delivers an Oscar-caliber performance, allowing glimpses of Whale’s pain and fear behind his facade of easy charm and barbed wit. Fraser’s natural performance perfectly contrasts with McKellan’s theatricality. As Whale gradually comes to terms with what he remembers about the trenches of World War I, his stifling childhood, and his dubious achievements as a Hollywood director, the film turns into a richly realized evocation of a man struggling with inner demons. This is clearly a labor of love for director Bill Condon; with Gods and Monsters he remakes his otherwise unremarkable career.