![]() In the Realms of the Unreal: The Mysterious Life and Art of Henry Darger

In the Realms of the Unreal: The Mysterious Life and Art of Henry Darger

Opens Fri., March 4, at Harvard Exit

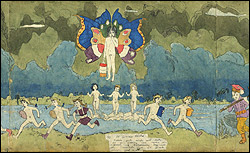

Henry Darger’s landlords made a stunning discovery when the 81-year-old former janitor moved out of his Chicago apartment shortly before his 1973 death: a 15,000-page novel, illustrated with hundreds of astonishing watercolors, some of them on scrolls of paper 10 feet long. Titled The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, the novel tells the story of, well, it’s actually hard to say, but it involves an epic war between some evil Civil War types and a bunch of little girls with penises. An unschooled artist with little confidence in his abilities, Darger incorporated figures traced from magazines, comics, and textbooks into his bright, posterlike compositions of vast battlefields, billowing clouds, and enormous flowers. Working for decades in complete isolation, Darger developed a unique, lush, almost Art Deco graphic language, combining the commercial art of his sources and the visions of his own mythological imagination.

This intoxicating, claustrophobic documentary by Jessica Yu plunges with headlong abandon into Darger’s world. There are no talking-head psychologists or art critics to provide a comfortable distance between us and the choking dust of Darger’s apartment, where Yu was allowed to film his dried-up paints, collections of twine and rubber bands, and towering stacks of manuscript. Using period newsreels and Darger’s own artwork to interpolate the sad facts of the artist’s biography and his rich inner life, Yu evokes the beautiful, sinister, obsessive mind of the man who is often called the greatest outsider artist of the 20th century. She is a master of Ken Burns–style tricks for bringing still images to life—the slow pan or zoom accompanied by music and ambient sounds—but goes further, actually animating Darger’s paintings to magical effect.

Those who expect a kind of Alice in Wonderland Goes to War, however, should be warned that not only are the little girls in Darger’s pictures often naked, they are also shown being stabbed, strangled, shot, and crucified. Yu glosses over none of this but makes it clear that Darger’s girls were as much subjects as objects, embodiments of his own childhood suffering and tormented relationship with God. Darger was—surprise!—a Catholic, and his art is here seen to be that of an ecstatic, if unbalanced, religious visionary. (NR) DAVID STOESZ

The Jacket

Opens Fri., March 4, at Metro and others

In John Maybury’s scruffy little time-trip flick, Adrien Brody goes through so many changes, it’s as if he’s tripping through not time but film history. At first, his character, Jack Starks, is a Marine in the first Gulf War, in 1991, which looks a bit like a darker version of Three Kings. (Unsurprising, since the producers include Steven Soderbergh and George Clooney.) He gets a head wound that, back home in white-trash Vermont, gives him memory problems reminiscent of Memento.

While hitchhiking, Jack restarts a stalled truck that has stranded a little girl and her stoned mama (Kelly Lynch, resembling her Drugstore Cowboy character 20 years later, apparently with no sleep in between). Then he gets involved in a Thin Blue Line–like cop shooting for which he’s erroneously blamed, à la Hitchcock. At a One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest authoritarian madhouse, pill-popping mad scientist Kris Kristofferson straps him into the titular straitjacket, injects him with psychedelics, and sticks him in a dark drawer in the morgue. His hallucinations are like Altered States, except they foretell the future, as in Slaughterhouse-5, Minority Report, or The Butterfly Effect.

He time-trips to the future, where the little girl he’d helped in 1991 has grown up to be Keira Knightley attempting to ape Courtney Love. She picks him up in her grungemobile and improbably takes him home. He commutes between the nuthouse and the grungy future via the morgue-drawer hallucinations, bringing back information that convinces everyone—including fellow inmate Daniel Craig—he’s even crazier than they thought.

I won’t spoil the very modest surprises in the plot, except to say that they involve an alternate future for Knightley involving a fancier car (kind of like the ending of Back to the Future) and, for some reason I can’t figure out at all, a gratuitous subplot starring Jennifer Jason Leigh (who apparently hasn’t slept since Fast Times at Ridgemont High) as a kindly nuthouse nurse who’s also caring for a seemingly autistic child.

Unfortunately, the plot is ultimately a muddle that resolves itself with a big, dumb gimmick recalling D.O.A.— Jack discovers he’s got four days to prevent his own death!—which deprives the ending of all but formulaic payoffs. Too bad; all that talent, all those cool movie allusions, but The Jacket never figures out how to be a real movie in its own right. (R) TIM APPELO

Travellers & Magicians

Runs Fri., March 4–Thurs., March 10, at Varsity

The path to wisdom winds uneventfully through some beautiful terrain in this Buddhist fable from Bhutan, although those on the road seem mostly oblivious to the scenery. Mainly they’re intent on thumbing a ride to the city, then passing the time when cars and trucks fail to stop for them. You could compare the movie to The Canterbury Tales, since one of the hitchhikers is a talkative monk, only he’s got just one tale to tell. His captive audience includes a villager freighting apples to market, an old paper merchant and his cute 19-year-old daughter, and a citified, educated, and rather crassly Westernized government official, Dondup (Tshewang Dendup), who’s impatiently trying to make his connection to America—where, he understands, the streets are paved with gold.

Constantly checking his watch, playing air guitar to god-awful ’80s pop, preening his long hair, and generally talking down to all the peasants he meets, Dondup is rendered like the very caricature of a wanna-be Westerner, right down to his “I ♥ NY” T-shirt. Like Dondup, viewers may roll their eyes when the monk begins lecturing him on the evils of smoking, haste, and ambition (“Hope causes pain”). Also like Dondup, however, since there’s not a whole helluva lot else going on in Travellers, viewers will have no choice but to listen to the monk’s parable, which is interspersed with the hitchhikers’ progress toward the city.

In the story-within-the-story, an ambitious lad washes out at magic school, then takes to the road on an enchanted horse. Bucked off in the forest, he falls for the young wife of a reclusive old woodsman. Eventually she lures him into bed, and murder, which introduces an element of James M. Cain into the Buddhist text. If that sounds exciting, it isn’t; Zhang Yimou does that noirish kind of peasant-adultery-murder thing much better, as in Ju Dou, while the director here, Khyentse Norbu, is stronger with the peasant-platitude-whimsy stuff, as in The Cup.

So the path to wisdom is ultimately rather dull. Dondup patiently listens to the monk; he makes nice with the girl; he even learns to be a bit less selfish. Will the monk’s cautionary story have any effect on him? Will he woo the girl, return to his village, and care for his aged parents? Travellers is sophisticated enough to avoid an obvious ending or moral. Dondup says of his ticket to America, “This is the chance of a lifetime.” The monk is kind enough to avoid an obvious rebuke: “Yes, but only of this lifetime.” (NR) BRIAN MILLER