For its 29th festival, Toronto went for broke with the deepest, richest, most daring lineup I can remember in roughly 20 years. Politics were on the screen in every form, especially sexual, in films that gleefully shattered every boundary: Lukas Moodysson’s blistering A Hole in My Heart (homegrown pornography); Michael Winterbottom’s 9 Songs (explicit, real, but nonpornographic sex); Ousmane Sembene’s Moolade (genital mutilation of young girls), whose off-screen depiction of these surgeries softens the act—except for his white-hot fury.

The press screenings were on a hell-bent track from the very first day, which made collegial word of mouth almost impossible—by the time you found something, its screening was past. After the first weekend, old hands, trading the inevitable “What’ve you seen?” found perfectly reliable friends claiming to have seen marvels that no one else had heard of . . . let alone seen. It was Rashomon run riot.

So, you played hunches: Would it be Alexander Payne’s Sideways, a lighter-than-light romp in the wine country, or two hours and 20 minutes of The World, a semi–love story set in a Beijing theme park, by a director whose three previous films have been relatively underground affairs? Sideways will be here soon enough; I took the long shot and never looked back.

Director Jia Zhangke’s original, absorbing drama sets the contradictions of “new China” against the backstage life of singers and dancers at a 141-acre Disneyland-style park, where scale models and a monorail bring the world’s wonders—the Taj Mahal, the Eiffel Tower, the Egyptian pyramids, Big Ben, et al.—to China’s travel-happy (emigration hungry?) middle class. The Las Vegas–style glitz exists in stark contrast to the loneliness and alienation of the performers and guards, most of them from the countryside, all desperate to get ahead or even make connections in a baffling society whose worldliness is actually as deep as the plaster walls of the park.

With The World as a high-water mark, I decided to zero in on films without distributors, ones with “difficult” subjects, or ones like the heroic, essential Henri Langlois: The Phantom of the Cinemateque, whose three-and-one-half-hour running time suggests an iffy afterlife of festivals only. The pickings were glorious. Here’s the tiniest cross section to check at SIFF time.

The Sea Inside was potentially off-putting, between the high gloss of director Alejandro Amenábar’s earlier films (Open Your Eyes and The Others) and a potentially weepy subject: the right to die. Instead, its eloquently reasoned script and the majesterial performance of Javier Bardem (Oscar nominated for Before Night Falls) gave it lingering power and poignancy. Bardem plays real-life sailor and writer Ramón Sampedro, paralyzed from the neck down after a swimming accident in his late 20s, whose case in the Spanish courts gained worldwide attention a few years back. After 30-some immobile, bedridden years, he wanted a way out of a life in which he felt he was barely a participant.

Bardem’s physical transformation to the 20-years-older Sampedro took five hours each morning; it’s close to miraculous, but no less so than his evocation of Sampedro himself. Warm, amused, engaged, and intelligent, he’s a man who draws people to him: a feisty working-class woman (Lola Dueñas from Pedro Almodóvar’s Talk to Her) who comes to persuade him that life is worth it; and an elegant lawyer (Belén Rueda) whom he has picked precisely because she has a debilitating disease—and presumably a deeper insight into his wishes. No matter your point of view, the film provides a moving spokesperson to embody it. Little wonder it won best film and best actor honors at Venice.

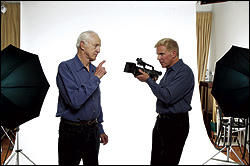

Feistiness is absolutely at the heart of Tell Them Who You Are, filmmaker Mark Wexler’s uphill battle to document his legendary cinematographer father, Haskell Wexler, his own way, thwarted at nearly every turn by Haskell himself. The two-time Academy Award winner (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Bound for Glory) knows how Mark should shoot, light, and edit his film—and vote, as well; interviews with Cuckoo’s Nest director Milos Forman and producer Michael Douglas, suggest that this is normal Haskell behavior, and he himself is not shy about saying he could have done a better job directing every film he photographed.

Just when you’re fed up to the teeth with this 81-year-old prima donna, Mark lobs his grenade: Haskell’s visit to Mark’s mother, whom he left after what even Haskell calls 30 “not bad years” of marriage. Now an Alzheimer’s patient, she still looks like the handsome artist of earlier footage, and as Haskell nuzzles her face, whispering, “We’ve got secrets,” as tears course down his face, it’s a naked moment and a turning point in the film’s empathy. Among the also-seens in Tell Them: Jane Fonda (who knows a thing or two about dads for whom intimacy was not a gift); Julia Roberts; and, most touchingly, the late, great cinematographer Conrad Hall, Mark’s surrogate father and Haskell’s closest friend.

Finally, the magnificent Nobody Knows, which director Hirokazu Kore-Eda (Mabarosi, Afterlife) expanded from a Tokyo newspaper clipping. In it, he manages nothing less than a portrait of the essential nature of children, in this case four (by different fathers) living secretly in a small Tokyo apartment. Their flaky, semi- employed bubblegum-voiced mother (a Tokyo TV performer, brilliantly cast) has presented the eldest, Akira, a grave, 12-year-old boy, to the landlords and smuggled in the other three in suitcases. Forbidden even to step out on the balcony, except to do laundry, told that “nobody important ever went to school,” the four unquestioningly make up routines to fill their days as she flits in and out of their lives.

When she decamps for good, she entrusts the children to Akira, who allows the others to hope that she’ll return. Over the months that follow, as their structured lives crumble, as the gas and electricity go out and they’re forced to venture out into a world that barely notices them, their family bonds never fray. With meticulous, compassionate detail, Kore-Eda suggests that their innocent resilience is an inherent quality of childhood; wrenchingly, they can also be seen as the embodiment of disposable children the world over.