One of the most interesting things about Cosmopolis, writer/director David Cronenberg’s extraordinary adaptation of Don DeLillo’s novel by the same name, is that it’s based on the first script Cronenberg has both written and shot since 1999’s eXistenZ. Additionally, Cronenberg’s adaptation of Cosmopolis marks the first time he has adapted a work since his 1996 version of J.G. Ballard’s Crash. Then again, most of Cronenberg’s films are at least loosely adapted from preexisting material, even if it’s just a short story, as in the case of The Fly, which was based in part on George Langelaan’s short story.

“Each adaptation is a completely different project,” Cronenberg said during a recent phone interview. “I don’t have an approach I try to impose on that process because each book is different, and I’m different, and what I try to achieve with the movie is [different] in each case.” He added: “The two media [i.e., film and prose] are really different, and you are inevitably making choices. There is no exact way to translate something directly to the screen. We’re creating a new thing. You have to accept that. You will therefore be making all kinds of changes, consciously or not.”

Adapting DeLillo’s densely plotted and surreally imagistic novel posed a unique challenge to Cronenberg, who cranked out a screenplay in three days. DeLillo’s book follows hyper-successful stock trader Eric Packer (Twilight‘s Robert Pattinson) on a day-long, self-destructive trip to get a haircut. Along the way, he meets up with his various financial advisers, each of whom reveals to the reader a little more of Packer’s contradictory feelings he has toward the idea of killing himself.

Cronenberg only decided to go through with adapting Cosmopolis after whittling it down to just its dialogue and discovering that the book’s narrative could in fact be adapted to the screen. Much of the book is composed of Eric’s private thoughts; by making the film’s narrative primarily composed of Eric’s dialogue, Cronenberg changed the context of DeLillo’s story. “I was not addressing the inner fantasies and the inner workings of Eric’s mind in the movie because I feel you can’t,” Cronenberg said. “One of the things I feel like you can do, even in a really bad novel, is that inner monologue. You can’t show that mental state at all in cinema. So we have to do something else.”

Cronenberg also did not want to find a way to approximate ideas or sentiments that he felt could only be digested in DeLillo’s original prose. For example, when DeLillo asked Cronenberg how he would adapt excerpts from a notebook written by Benno Levin (Paul Giamatti), a mysterious frump who stalks Eric throughout the film, Cronenberg’s response was characteristically direct: “You handle it by leaving it out.”

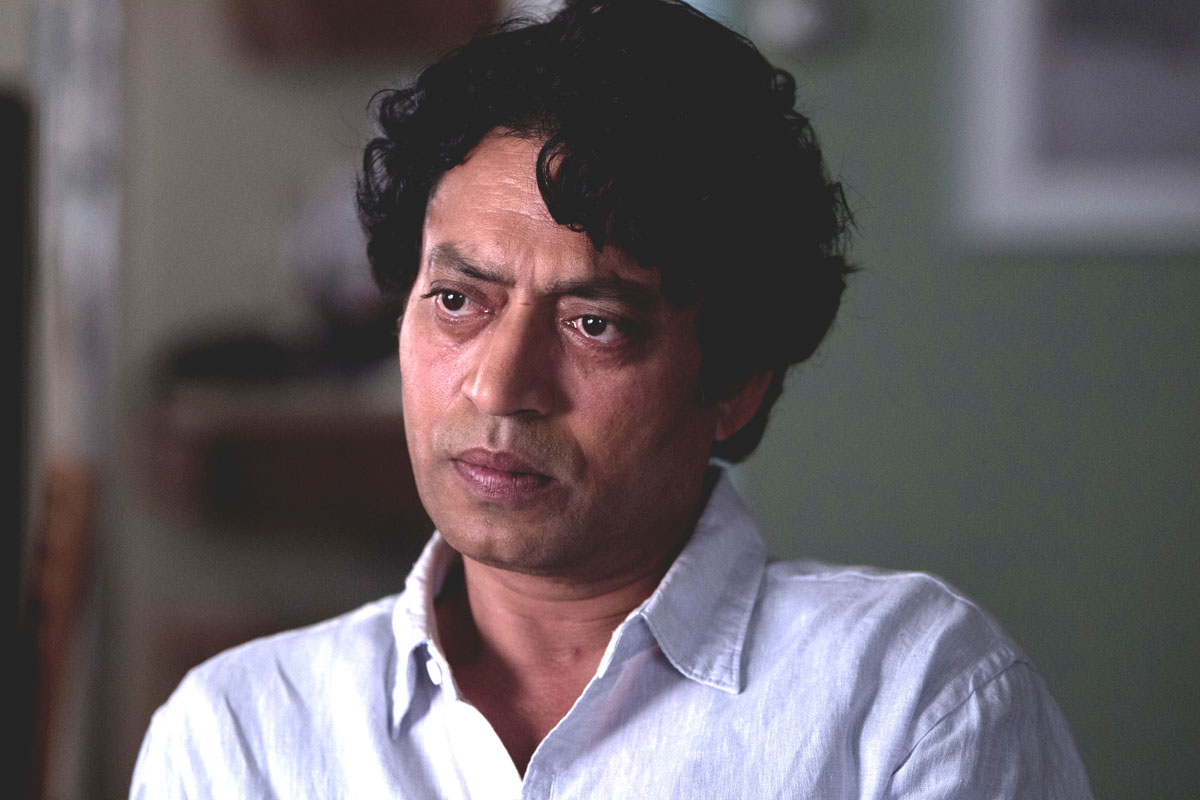

“There’s no way I can make a voiceover of someone reading Benno’s journal,” Cronenberg said. “It’s a complete admission of failure when you have somebody read you the novel like you’re a kid at bedtime. That reads as if you’ve failed to reimagine the work as cinema. But what I do give you is Paul Giamatti’s face, and his eyes, and his face, and his hair, and his body, and that gives you something you don’t get in the novel. That’s the trade-off.”

Similarly, another key change to the book’s narrative came when Cronenberg cast Pattinson, who, perhaps appropriately, plays a young hotshot who’s prematurely contemplating his own obsolescence. Cronenberg said that he never really talked to Pattinson about the film’s main themes or what Eric symbolized. Instead, he said Pattinson was more concerned with whether or not Cronenberg thought he was good enough to play Eric. “We didn’t discuss any of these abstract things,” Cronenberg recounted. “You can’t shoot an abstraction. You cannot photograph an abstraction. And likewise, an actor cannot act an abstraction. You can’t say to an actor, ‘You will be the embodiment of American capitalism.'”

Ultimately, what attracted Cronenberg to Cosmopolis most was the challenge of turning such a cerebral book into a film. In fact, he was so focused on conceptualizing DeLillo’s narrative that he didn’t even hear the writer’s dialogue spoken aloud until his cast was rehearsing. “You have to work with the reality,” Cronenberg said. “The emotional, physical, and psychological reality of a guy in a limo talking to one of his financial advisers, his security guy. And you go with the specifics of the moment, and you evolve from there.”