Seattle Opera gave a press lunch last week to introduce its production team for next spring’s Macbeth. Designer Robert Israel mentioned that this Macbeth would be partly inspired by Octavio Paz’s essay interpreting Shakespeare’s original play as a critique of modern capitalism. Now, I’m as big a Michael Moore fan as the next Nation subscriber, but I like my critiques of capitalism head-on, rather than anachronistically teased out of a work of art. Of course, I’m eager to be persuaded by such a Macbeth, or indeed by any director’s approach to any opera—even if Marxist revisionism is possibly the single most hackneyed aesthetic stance of the past half-century. The irony of the announcement, however, is that the company is nearly through its production of Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungs (ends Sunday, Aug. 28, at McCaw Hall; 206-389-7676), the great strength of which lies in its director’s willingness to take the story at face value.

In Stephen Wadsworth’s hands, this Ring gives us gods, heroes, monsters, love, greed, and betrayal—just as Wagner intended. Yet, tradition or faithfulness to Wagner are not Wadsworth’s main priorities: He’s chosen to focus on creating complex three-dimensional characters and the inherent drama of their connections and conflicts. Emblematic of his vision are this Ring‘s Wotan and Fricka. I’ve seen no chemistry, no poignance, between operatic lovers like that of Greer Grimsley (his debut in the role) and Stephanie Blythe; the very first and last images in the entire tetralogy display their affection. Blythe, with her soaring, melting soprano, makes it clear that her implacable demands—to punish Siegfried’s human parents for incest and adultery— are motivated by her conscience and a desperate love for her flawed husband.

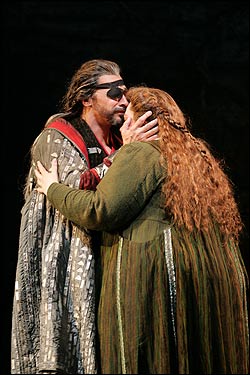

The beauty and liquid flow of Jane Eaglen’s voice and the ringing sureness of her high notes never fail her. She’s becoming less theatrically inhibited, and achieves some real passion in Götterdämmerung‘s Act II confrontations. What really makes this a performance of genius, however, is the way her Brünnhilde ages over the three operas in which she participates. In Die Walküre, Eaglen sounds rosy fresh, even girlish, with a voice slightly, if notably, lighter and smaller than Blythe’s Fricka or Margaret Jane Wray’s Sieglinde; in the final love duet of Siegfried, Eaglen is in full bloom; and for Götterdämmerung, she adds a touch of burnished brass.

Conscious or not, such touches are representative of the intelligent subtlety of the entire cast’s portrayals. Alan Woodrow’s Siegfried is, in succession, bumptious, dashing, and villainous, aided by his secure and muscular tenor. Peter Kazaras, wry as the trickster fire god Loge, is also the first to sense doom on the horizon, bringing Das Rheingold to a potent climax. The giant Fasolt and the warrior Hunding, both enlivened by the volcanic bass of Stephen Milling, have their sympathetic sides, while Gidon Saks brings a subtle leonine charisma to the thug Hagen (what an Iago he’d make). Ewa Podles—a magnificent, old-school command-the-audience diva—possesses an otherworldly, almost tenorlike low register perfect for the seer-goddess Erda.

There are also generous scatterings of wit: dry, chuckle-inducing ironies in Jonathan Dean’s colloquial supertitles, and an imaginative interpolated sight gag in Siegfried. Plus, we get fire and a dragon and a real horse and Rhinemaidens turning midair somersaults—all the things that make you feel like an 8-year-old at the circus.

Two members of the splendid orchestra, led boldly by Robert Spano, must be mentioned: Mark Robbins for Siegfried’s stunningly robust horn calls, and Jennifer Nelson for extensive bass clarinet solos of gripping evocativeness. Thomas Lynch’s sylvan sets, unveiled at the 2001 premiere of this Ring, are already part of Seattle Opera legend.

I can’t imagine I’ll ever see a better Ring in my life. At the least, it’ll spoil me for others not as carefully thought out, as lovingly performed, or as technically lavish as this one.