South Africa’s William Kentridge is esteemed in high-aesthete circles because he’s a political artist who addresses apartheid, and does so in the trendy genre of video art. But his popularity goes way beyond the cognoscenti—he’s a bona fide international art star.

He’s so bizarrely diverse, it’s hard to get a fix on him. Besides the films, drawings, prints, tapestry, sculptures, and stereoscopes in his Henry exhibition (a superb quick introductory survey of his genius), he has recently put on a stage performance in Kane Hall, has directed opera [see Gavin Borchert’s review], is showing prints at Greg Kucera, and has a blockbuster show up at San Francisco’s SFMOMA.

Why is Kentridge riding so high? Because his art gives you the last thing you’d expect of his chosen genre: pure pleasure. He avoids the shrill, smug obviousness of much political art, and the interminable dullness that makes watching so much video art, even important work, feel like doing penance. Kentridge’s animated films have the schematic, primitive power of 1920s Ub Iwerks cartoons, and big ideas expressed in a compelling narrative. They’re intimate, personal, immediate, not distant like much video art, with the driving engine of every important film in cinematic history—action.

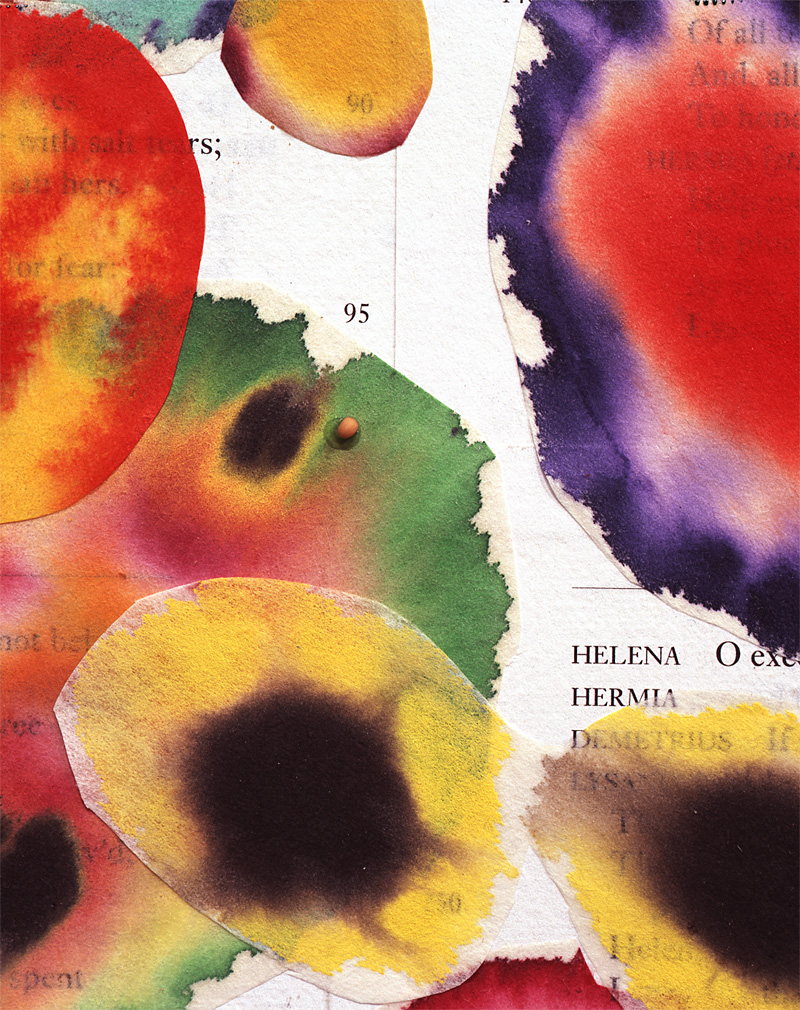

Kentridge, who’s white and in his early 50s, also dodges clear political readings. Consider the difference between Kara Walker’s silhouettes of American blacks getting raped and lynched by Confederates and Kentridge’s graphic work Portage. In the latter, torn-paper silhouettes of burdened native people struggle across the pages of a 1906 French encyclopedia studded with engravings of men in powdered wigs, flags, chains, and venomous snakes. Walker’s point about the past is bayonet-sharp; Kentridge’s ideas are more oblique. He’s about right now—the aftermath of violence, how we live with painful contradictions. And the evil isn’t just racism, it’s the impersonal power of technology, the ugliness of industry, the jackbooted march of progress. At points, his films are like ’50s movies in which robots take over the world.

Though most people know him for his video work—he’s up there with Bill Viola and Gary Hill—it’s his extreme facility in drawing that powers his films. They’re essentially charcoal renderings that move and morph. His motto: “No script, no storyboard.” He gets into the drawing zone, gets out of the way, and lets his sure hand and intuitive process take over, recording an image, a moment, then erasing and redrawing, over and over.

A human head becomes a clock. A woman becomes a wall of numbers. A telephone belches blackness that obliterates a man. In Medicine Cabinet, a film projected into the glass-shelved interior of a bathroom cabinet installed on the gallery wall, a man’s face appears next to the mirrored door reflecting your own face watching him. The toiletry bottles turn into dust, then a barren landscape; a flapping bird vainly trying to escape becomes a fish who can’t swim away. Kentridge makes the cabinet seem like a film screen, a tiny stage, a Cornell box revealing a mind’s interior, a birdcage, a fish tank, and, always, a kinetic sculpture you can’t take your eyes off.

It’s also a kind of newsreel. Screaming headlines fill the cabinet with violence, hinting that this is one mirror whose revelations people may not bear to see. Everything in Kentridge springs from the real post-apartheid world. His father, a knighted lawyer, led the inquiry into black leader Steve Biko’s death, and the metamorphoses in Kentridge’s drawings are akin to what his dad did when he obliterated the police officers’ whitewash and replaced it with the murderous truth.

But the films are not the only essential viewing at the Henry show. Take a close look at Kentridge’s utterly stunning series of aquatint etchings, Zeno at 4 am. Self-consciously reminiscent of Goya’s Caprichos and Disasters of War, these bold images, deftly executed, are full of quicksilver metaphors: a shower with blood instead of water, a man on radio-tower stilts, a colonially dressed woman with a telephone for a head, drawn with such finesse it works anatomically. The gestural images are small, but they make a big statement. The huge drypoint print Cassipers Full of Love, which depicts a South African riot-control tank as a box full of severed human heads, is a masterful expressionist drawing with the bold line and urgency of Käthe Kollwitz or Max Beckmann.

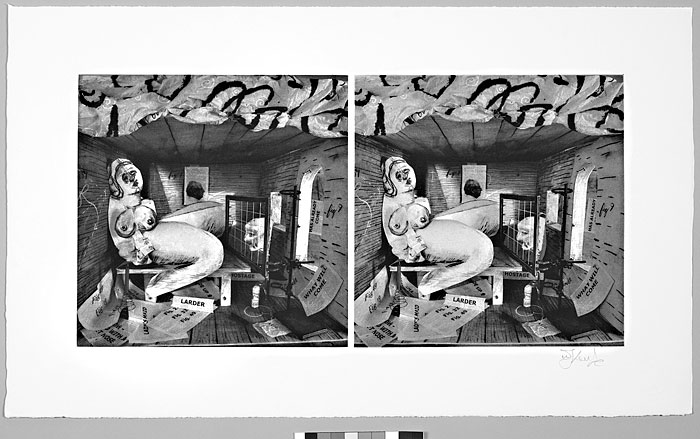

Kentridge reinvents drawing, not just in animation, but by updating the old-fashioned stereoscope (paired drawings viewed through twin lenses that make them 3D) and through an anamorphic drawing that becomes Medusa when reflected in a polished cylinder. True, without his startlingly original cinema he might not be as celebrated. But those films are simply records of a narrative process that takes life through fluid, confident drawing. They begin and end with a charcoal mark and the brilliant mind behind it.