When private collectors are generous enough to send their art on the road, the catalogue already written, a bottom-line-mindful museum isn’t likely to quibble about the contents. Shows traveling among institutions, involving Renoirs or Warhols, are far more pricey to mount. Which is not to say there’s anything cheap or shoddy about Indigenous Beauty: Masterworks of American Indian Art From the Diker Collection, which opened in mid-February. New York collectors Charles and Valerie Diker have a good eye, augmented by professional curators and buyers. Larger samplings from their trove have been favorably received at the Met, the Smithsonian, and the National Museum of the American Indian. (Here, some 122 objects are on view, with an additional regional sidebar of 60 familiar pieces called Seattle Collects Northwest Coast Native Art.)

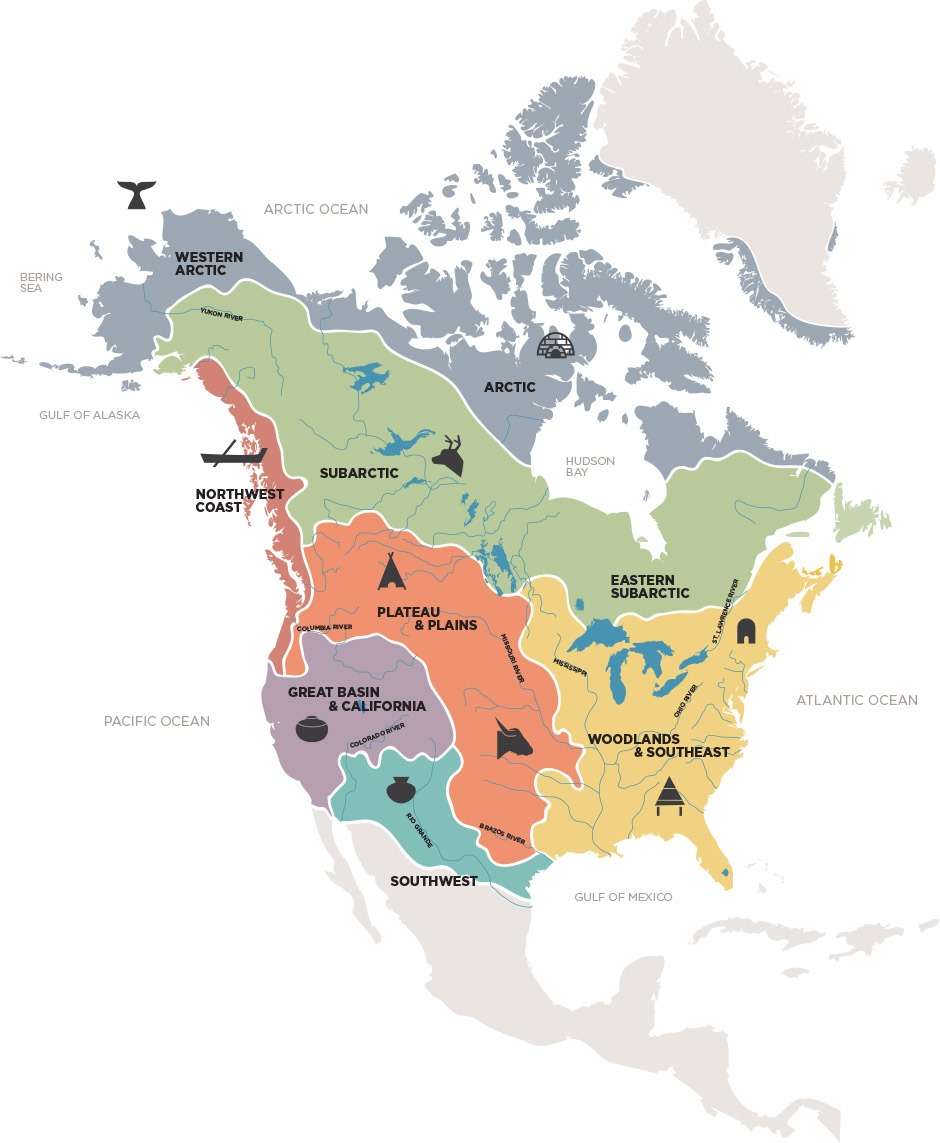

The limit to the Diker exhibition is, paradoxically, its breadth. There’s a lot to see from every corner of the continent, including over 500 tribes and 2,000 years of history (up to the present era). You want Hopi pottery? You got it. Navajo blankets? Those too. Tlingit tunics and Washoe baskets? Check and check. Also on view are pipes, drums, bowls, war clubs, ivory carvings, rattles, rugs, moccasins, combs, dolls, purses, and even a bit of metalwork and ink-on-paper drawing—after those materials were introduced by European colonists. The fabulous glass beadwork also resulted from trading with new settlers, which helped create a late-19th-century market for Indian wares.

The show feels like a compressed visit to a dozen different museums scattered across the U.S., Canada, and Mexico—a sampler of sorts. You want to see more, but you also want to see more focus on history, tribe, or region.

At the show’s opening, Valerie Diker said the couple’s only collecting criterion was beauty—an unimpeachable if amorphous standard. (They also buy extensively in modern art.) That leaves the task of organization to visiting curator David Penney and his SAM cohort, who’ve devised 11 nodes of interest—primarily geographic and cultural, which somewhat contradicts the Dikers’ magpie aesthetic. Still, we’d be lost without it; numerous maps and wall texts also help with the navigation.

In keeping with the Dikers’ wide-ranging taste, Penney cites a “sense of modernism, of abstraction, and pattern” to indigenous art. Figuration is rare. Unlike millennia of Greek, Roman, and Christian traditions, there are no bearded gods and nubile nymphs to represent from the constellations and mythic tales. There’s almost no sense of narrative, as Penney admits: “In many cases, we’ve lost the knowledge of the stories they were trying to tell.” Despite recent scholarship, it’s difficult to grasp all the forgotten ceremonial and spiritual significance of these artifacts. (Native religious practices were outlawed from 1883 to 1978, during which time missionaries and schoolteachers also did their best to erase the old pagan ways.) Most everything exists in a vague, achronological past, not like the tidy Bible scenes or historical canvases of European art.

Penney sees in many of these artifacts “technology that has its aesthetic dimension,” meaning those portable, useful implements passed down through generations. If ceremonial aspects are often obscure, even today we can understand the urge to decorate a handmade tool. A carved wooden drinking cup from the Anishinaabe bears images of beaver and sturgeon—tokens of wealth (via trade) by the early 19th century. Likewise the baskets and ceramic bowls of Zuni and Pueblo culture were intended to be useful, to fit pleasingly into the hand, so why not also adorn them with geometric patterns pleasing to the eye? These objects are both valuable heirlooms and instruments of survival.

On the subject of tools, however, forget about bows and arrows, tomahawks, and other instruments of war. I counted maybe one metal-bladed knife (this after colonization) in a show that elides the violent subjugation of our continent’s original owners. But again, beauty is the Dikers’ collecting imperative, not dismal history. Though we do discern, in a 1920 drawing, a depiction of the 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn (aka Custer’s Last Stand)—the last great victory against the U.S. Army. After that: total defeat, poverty, the reservations, and roadside trinket stands.

While none of these creations were intended for display or veneration in the European sense of art, it’s their functional aesthetic that’s so powerful and affecting. Nothing here is merely decorative. If you’re going to make a pair of high-top Kiowa moccasins, why not make them lovely—with elaborate tassels and beadwork? If Picasso were a stone-age cobbler, and the art market didn’t exist, he might do the same. That culture of practical adornment is also seen in the luggage, litters, baskets, baby carriers, and other objects of transport used by the nomadic tribes of the Great Plains. And let’s note that, if you’re planning a trip to New York before May 10, the Met is now specifically featuring the Plains Indians—a far deeper view than the 11 sampling stations here.

Certainly the Dikers’ is a far better collection than the Old West trove recently donated to the Tacoma Art Museum by the Haub family. Everything’s of a higher quality than your average anthropology show at the Burke, which reflects Charles Diker’s Wall Street success. He and his wife began collecting in the early ’60s, before the resurgence of Native American rights and the new appreciation of cultures that had been flattened to stereotype by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, Hollywood, and TV. Still, I thought more of last year’s Deco Japan show at SAAM—also a private collection on tour—because its period and culture were so much more specific. The Diker Collection covers more ground, yet treads too lightly upon it.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

SEATTLE ART MUSEUM 1300 First Ave., 654-3121, seattleartmuseum.org. $12.50–$19.50. 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Wed.–Sun. (open until 9 p.m. Thurs.) Ends May 17.