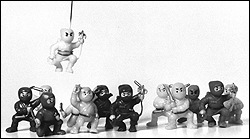

To be or not to be? The question has been posed a million times over, in an outrageous infinity of settings and adaptations and reimaginings, until the pertinent query becomes: To do or not to do? Can anything be new under the Shakespearean sun—or, in this instance, microscope? Tiny Ninja Theater’s Hamlet (part of Seattle International Nights at the Empty Space Theatre through Sunday, May 22; 206-684-7346) is the brainchild of Dov Weinstein, a bent and brilliant New Yorker who claims sole voice for his itty-bitty cast of inherently stiff actors— an assortment of plastic toys that get televised on video screens with all the invasive, wobbly reach of a live colonoscopy. Guaranteed, this is a version of Hamlet you have never seen. And if you do happen to go, you’ll likely never see the play in quite the same way again.

Residing somewhere between innovation and whimsy, Weinstein’s Hamlet discovers a heretofore untold of prince—the querulous ninja. He does for the Dane’s tale what director Todd Haynes did for the Karen Carpenter story, when that young, audacious filmmaker manipulated Ken and Barbie dolls to portray the tragic nexus of celebrity, family dysfunction, and anorexia in Superstar. Haynes’ film—to this day available only in bootleg form thanks to a legal clampdown by the Carpenter family—utterly reversed the inanimate plasticity of its Mattel figurines, creating a work that is ironically haunting, oddly moving, and humane.

Weinstein’s technical and artistic wizardry works a similar magic on Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy. Utilizing small, handheld digital cameras and skittering to and fro among numerous sets that are displayed on dueling video screens, Weinstein conjures a topsy-turvy universe where our expectations are alternately jarred and rewarded. Much as playwright Tom Stoppard did in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Weinstein continuously shifts perspectives, attacking uncharted areas of Shakespeare’s most dog-eared text. Here, the camera, as Laertes, peeks in on conversations or addresses the audience directly as Hamlet, swooning in and out of focus (is he truly mad?); Weinstein enacts the climactic duel between the pair by holding a camera in each hand, the two screens lunging and dodging at each other, stunningly depicting the vertiginous chaos of a sword fight.

Each image is met, at first, with laughter, though Weinstein is hardly playing this for easy yuks. If it seems a bit coy and clever—and, yes, funny—to drop poor Ophelia into a glass of water, the subsequent moment of the glass tipped sideways, with Ophelia floating languidly across the screen, is a scene of beautiful melancholy. Or take the Queen and King, portrayed here as smiley, oversized roundheads—they elicit all the creepy hilarity of clowns. “The comic and the capacity for laughter are situated in the laugher and by no means in the object of his mirth,” wrote Baudelaire, and surely there is something disorienting in beholding images as literal as they are odd. We are thrown back upon ourselves, and the imagination is sparked. Such is the puppet show.

Weinstein treats his production with a kind of joyful seriousness—like a smart, hyperactive kid telling himself stories with a snow globe—and, rather than distracting us, this propels us right to the dark heart of Shakespeare’s language and Hamlet‘s tragedy. It’s like being told something you didn’t know you already knew. And it must be said that, in reciting all the parts rather well with his hands completely full, Weinstein gives a virtuoso performance—all the more impressive for its apparent lack of self-consciousness and egotism. It would be a stretch to say that Tiny Ninja Theater inspires suspension of disbelief, though there are many moments when Weinstein’s legerdemain creates an atmosphere of wonder, even awe.