wed/3/13

Books

More Money, More Problems

Let’s start with the title. Mohsin Hamid isn’t serious about How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia (Riverhead, $26.95) being a how-to guide. It’s actually a slim, streamlined little novel, told mainly in the second person, about an unnamed protagonist’s self-made success in Pakistan. It’s also an unsentimental love story and a parable of globalization, a Horatio Alger tale in a post–Slumdog Millionaire context. Only Hamid, educated at Princeton and Harvard, today residing in Lahore, constantly interrupts his tale with remarks to the reader. This makes his hero less of a character than a case study, an exemplar of how poverty, corruption, fundamentalism, truck bombs, global markets, U.S. drones, and consumer aspirations are shaping Pakistan (or pulling it apart). First selling bootlegged DVDs, then later bottled water that’s anything but pure, Hamid’s striver becomes part of “a hypertrophying middle class, bulging from the otherwise scrawny body of the population like a teenager’s overdeveloped bicep.” But his is a cautionary tale: The bulge can’t last. Pakistan can’t support it (not yet, and maybe never). And while the state or business rivals can’t steal your health and happiness, those personal assets are no less ephemeral. Capital sloshes across markets; one man’s rise means another’s fall; the riches you accumulate will eventually disappear, leaving only filth behind. (In a related side note, the film adaptation of Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist, directed by Mira Nair, is currently making the festival rounds and should arrive this spring—or at SIFF.) Elliott Bay Book Co., 1521 10th Ave., 624-6600, elliottbaybook.com. Free. 7 p.m.

BRIAN MILLER

thurs/3/14

FILM

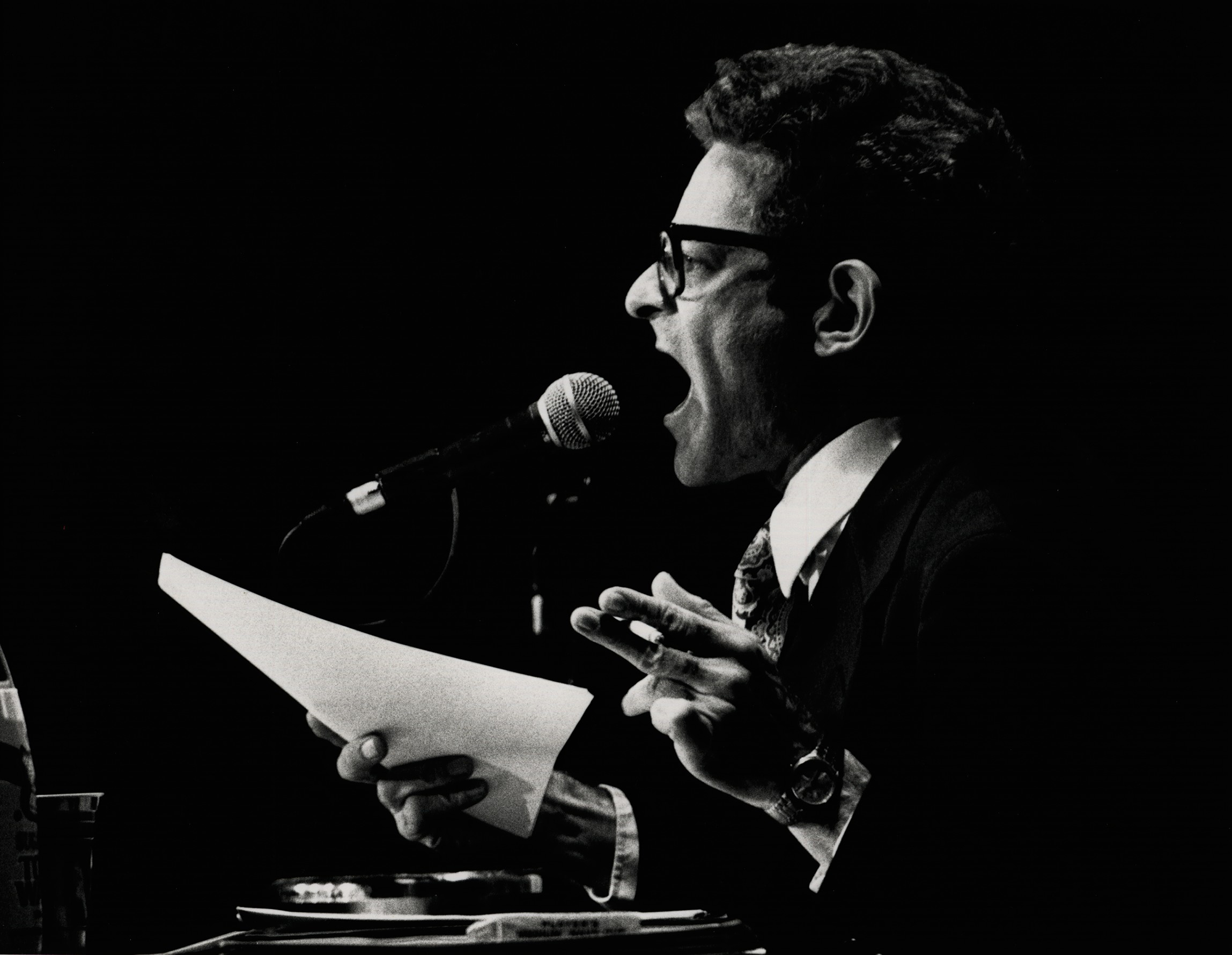

Late and Lamented

You worry about a guy who worshipped William S. Burroughs, and Steven Jesse Bernstein clearly made his friends worry long before he met his idol and preceded him onstage (at the Moore in 1988). Bernstein had mental troubles and substance-abuse issues most of his life. Following his 1991 suicide, the local poet was honored by a Sub Pop album and EMP exhibit, but the 2010 documentary I Am Secretly an Important Man is the tenderest tribute yet. The film is extremely well-sourced, with home movies and stills; director Peter Sillen had the luxury of picking through material compiled by others, including local curator Larry Reid. The doc sets Bernstein’s nasal verse to elegant streetscape montages of the city then and now. Friends and a few family members testify to Bernstein’s happy, conventional L.A. childhood and drug-impacted Seattle years. “Jesse was a true outsider,” says photographer Charles Peterson, who with other grunge scenesters—Kurt Cobain included—latched on to Bernstein’s raw words. “I’m not interested in making it in the literary world,” he claims; yet outside the punk-rock clubs, Bernstein was willing to do a reading in a storefront window at Nordstrom, to be interviewed—hilariously awkwardly—by Susan Hutchison on TV. Why he killed himself, and why he frequented the Elite after he married (and had two sons), is left unexplained. Straight biography isn’t the point here, and Bernstein’s contradictions, like Burroughs’, remain unresolved. Whether he’s a grunge footnote, a beatnik wannabe, or a beautiful, belated loser, the film allows you to decide. Grand Illusion, 1403 N.E. 50th St., 523-3935, grand illusioncinema.org. $5–$8. 7 p.m.

BRIAN MILLER

Books

Garden Hate

Sam Lipsyte had his breakthrough novel with The Ask (2010), but he’s long been an accomplished short-story writer. In his new

collection The Fun Parts (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $24), Lipsyte repeatedly touches upon themes of grievance and humiliation (often rooted in a chubby Jersey youth in the ’80s). From that bitter well is his characters’ resentment born. And from their resentment comes Lipsyte’s splattering font of angry, disgusted, and hilarious prose. In “The Wisdom of the Doulas,” for instance, a self-styled male doula increasingly alarms the family whose infant he’s tending. With a ninja fetish and faked credentials, Mitch the “doulo” (as he insists on being called) rejects the need for an official diploma. “Did a piece of paper educate you on newborn care?” he demands. “Did a piece of paper keep all the balls of nurturing in the air?” Mitch sees in the newborn’s unwrinkled perfection the obverse of his own fallen corporal state, “deep into cell degeneration or, worse, relocation.” Hair is moving from his head and sprouting between his shoulder blades. He’s broke, middle-aged, and estranged from his family, and he wants a fresh start. That’s what babies represent; and in his oafish, inappropriate way, Mitch does actually love babies and their mothers. What does he get in return? Abuse, rejection, throwing stars, 911 calls, and Tasers. Following tonight’s reading, Lipsyte will conduct a Q&A with local novelist Ryan Boudinot (Blueprints of the Afterlife). Expect New Jersey and the ’80s to come up, like bile. Richard Hugo House, 1634 11th Ave., 322-7030, hugohouse.org. $5. 7:30 p.m.

BRIAN MILLER

fri/3/15

FOOD/BOOKS

Profiting From Endorphins

Forget about a sweet tooth: The human body has sugar receptors in 10,000 taste buds scattered across the tongue and lining the stomach and esophagus. And as investigative reporter Michael Moss reveals in his startling Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us (Signal, $32.99), processed-food producers are dedicated to stimulating every one of them. Given unprecedented access to the masterminds behind the $1 trillion processed-food industry, Moss was able to reconstruct how companies such as Kraft and Coca-Cola use brain scans, manipulated fats, and chemically altered sugars to methodically engineer addictive snacks. Eaters love the results: The average American now consumes 70 pounds of sugar a year, a figure that pains even some former food-company bigwigs. “I was amazed by how many people I found who had regrets,” Moss says. Still, 60,000 processed products aren’t about to disappear from grocery shelves (where most of them are strategically positioned at eye level.) “This is not a book about not eating processed food,” Moss says. “It’s about taking control of what you’re eating.” Town Hall, 1119 Eighth Ave., 652-4255, townhallseattle.org. $5. 7:30 p.m.

HANNA RASKIN

sat/3/16

Stage

Fallen on Hard Times

It’s impossible to watch the Maysles brothers’ 1975 documentary Grey Gardens without wondering how its mother/daughter subjects ended up in their isolated, decrepit estate, full of cats and trash. How did these well-born women become such bizarre, sometimes incomprehensible characters? Edith Bouvier Beale and her daughter Edith were, after all, cousins of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis, but the contrast between their lives couldn’t be more shocking. The Tony-winning 2006 musical Grey Gardens, jointly produced here by ACT and the 5th Avenue Theatre, takes some liberties with the backstory of Big Edie and Little Edie, adding songs to boot (music by Scott Frankel, lyrics by Michael Korie, book by Doug Wright). Under the direction of Kurt Beattie, recent SW cover girl Jessica Skerritt plays the young and beautiful Little Edie in Act 1; she dreams of showbiz stardom and is engaged to Joseph Kennedy (JFK’s older brother). The songs she sings are flashy and snazzy, reflecting Little Edie’s gilded lifestyle. But the sea change occurs at the end of Act 1, when Big Edie (Patti Cohenour, who plays the decades-older older Little Edie in Act 2) inadvertently ruins her daughter’s future. Act 2 is the story we know from the Maysles’ doc, set 30 years later in the crumbling household where Big Edie (now Suzy Hunt) and Little Edie share a strange co-dependency. Though Skerritt doesn’t appear in Act 2, she says the songs change and get sadder: “The music is more atmospheric and spooky . . . It reflects the changed aura of the place and the squalor they’re now surrounded by.” (Previews begin tonight. Opens Fri., March 21. Ends May 26.) ACT Theatre, 700 Union St., 292-7676, acttheatre.org. $55–$77. 8 p.m. ERIN K. THOMPSON

Visual Arts

It’s a Gift

Art collectors, like the Wrights or the Shirleys, tend to be rich and prominent. That does not describe Dorothy and Herbert Vogel, who began buying art in New York in the early ’60s. He was a postal clerk and she a librarian. They favored minimalist and conceptual works, which tended to be small and could fit in their apartment. When four decades later they approached the National Gallery about donating their collection, it had reached 5,000 pieces (!). Of that, the National Gallery accepted about 1,000, and thus The Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection: Fifty Works for Fifty States initiative was launched. In 2008, SAM was designated this state’s beneficiary, and today those works are going on view. Artists include Stephen Antonakos, Sol LeWitt, Terry Winters, Cheryl Laemmle, Robert Mangold, and others. If these are not boldface names, they represent a postwar art scene that never blew up to Warhol or Pop Art proportions. The Vogels were careful, tasteful, modest collectors who befriended many New York artists, establishing career-long bonds. And there weren’t as many categories and theoretical flavors to guide their acquisitions, Dorothy Vogel told The New York Times in 2008. “It was a lot easier in those days,” she said. “We just bought what we liked.” Sadly, Herbert Vogel died last year. The Vogels had no children, but they leave a large legacy. (Through June 30.) Seattle Art Museum, 1300 First Ave., 654-3100, seattleartmuseum.org. $12–$20. 10 a.m.– 9 p.m.

BRIAN MILLER

Sports

Bragging Rights and Wrongs

The antagonism between the Seattle Sounders and the Portland Timbers, who clash tonight already in only our second MLS match of the season, involves a level of disdain more intense than that of most sports rivalries. It seems to stem from the peculiar arrogance of Timbers supporters: Their self-regard is through the roof; they can’t stop posturing as iconoclastic upstarts, yet they’re rigidly judgmental. They’re navel-gazingly obsessed with their own hipness and authenticity (their most damning insult for their rivals is “corporate”), and they’re ridiculously overproud of their occasional achievement, considering how often they whiff it . . . Huh. Rereading this, I realize I have just also described The Stranger. CenturyLink Field, 800 Occidental Ave. S., soundersfc.com. $29–$98. 5 p.m.

GAVIN BORCHERT

sun/3/17

Stage

He Feels the Need to Knead

Bread isn’t the first thing that comes to mind among the performing arts. Yet when the act of kneading dough is paired with what On the Boards’ Sean Ryan calls the “exuberant whistling of Vivaldi’s ‘Four Seasons,’ ” it becomes a portrait “of art within the physical body doing everyday things.” In the season’s third and final 12 Minutes Max, the long-running program will feature baker Campbell John Thibo performing his Bread, Water. Also on the bill: music from JR Rhodes, dance from Elia Mrak, and performances by Vanessa DeWolf, Zoe Wilson, Jeffrey Frace, and Kelsey Wilk—the latter reinterpreting the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, no dough required. Washington Hall, 153 14th Ave., 622-6952, ontheboards.org. $8. 7 p.m. (Repeats Mon.)

GWENDOLYN ELLIOTT

Dance/Film

These Vagabond Shoes

All too often, dance films get compartmentalized—you’re either looking at a classic Hollywood musical or an experimental art film. Luckily, the smarty-pants directors at Velocity Dance Center and Northwest Film Forum are programming a combination of the two, pairing a mainstream feature with an alternative short for Dance Cinema Quarterly. Their first program matches two films about New York City as a community of immigrants: West Side Story, with Jerome Robbins’ astonishing choreography, and Meredith Monk’s contemplative Ellis Island. It’s not really likely that Monk modeled her opening sequence, a slow approach to the island ending in a ramshackle warehouse, on the breathtaking flyover of Manhattan that begins West Side Story, but without this match-up, we might not even have known to ask the question. Northwest Film Forum, 1515 12th Ave., 267-5380, nwfilmforum.org. $6–$10. 8 p.m.

SANDRA KURTZ