It can be easy to forget about troubles in distant countries when so many crises explode into the headlines with disturbing regularity: New Orleans, the Pakistan-Kashmir earthquake, Iraq. And then there’s Darfur.

It’s harder to forget when you see suffering graphically depicted in crayon. A new exhibit opening today at UW’s Odegaard Library (through Sunday, Feb. 22; 206-543-2990) aims to remind people of the ongoing violence in the western Sudan, where up to 200,000 people have been systematically killed and as many as 2.4 million displaced since 2003, according to the United Nations.

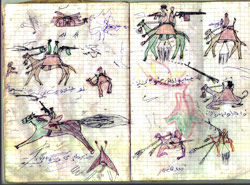

“The Smallest Witnesses: The Conflict in Darfur Through Children’s Eyes” presents 27 drawings by children, ages 7 to 17, living in refugee camps along the Chad-Sudan border. Their pictures depict the horrific scenes they have witnessed. Many are primitive, some mere stick figures, but others are sophisticated and disturbing in their specific details: Kalashnikov rifles, huts on fire, victims sprawled on the ground, some clutching cell phones in a futile gesture of calling for help. Clearly this is a way for children to express experiences for which there are no words.

When Michael Tarlowe read about the exhibit in New York, he asked the sponsor, Human Rights Watch, how to bring it to Seattle. “I decided that this was the kind of thing which might actually get people motivated to speak out and take action, seeing such disturbing images by innocent children,” says Tarlowe, owner of a local record label and activist with SaveDarfurWashingtonState. He plans to give visitors a pamphlet of “action items” to do something about the crisis after they leave the exhibit.

“These children have witnessed things that no child should see,” says Dr. Annie Sparrow, a pediatrician from Perth, Australia, and one of the researchers from Human Rights Watch who interviewed refugees in the camps in February 2005. While talking to the parents about sexual violence in Darfur, Sparrow and her colleague, Olivier Bercault, offered crayons and notebooks to engage the children.

“I never asked them to draw scenes of war. I let them draw whatever they wanted,” says Sparrow, and the results were shocking: “This is my hut being burned. This is a tank. This is a woman being shot in the face,” they told her. Says Sparrow, “They actually show very clearly how all the rules of war are being broken, as laid out in the Geneva Convention. They show the crimes of war.” The drawings also present corroborating evidence of the Sudanese government’s role in the killings, despite its denial of involvement, says Sparrow.

“We know that the Janjaweed [the militia committing the violence] only have horses and camels and various types of assault rifles,” explains Sparrow. “It’s the government of Sudan that has the tanks, the Antonov planes, the MiG fighter planes, the armored personnel carriers—what we call the arsenal of war. And that’s why the drawings are so fascinating. They have this whole new dimension of illustrating the complicity of the government of Sudan as the true architect of the war.”

“Children’s drawings of war are not new, of course,” Sparrow points out. “They go back at least to the Spanish Civil War.” This is perhaps the saddest truth of the exhibit—that children are increasingly the victims of war. Last March, UW Spanish professor Anthony Geist curated a similar but broader collection at UW’s Jacob Lawrence Gallery, “They Still Draw Pictures: Children’s Art in Wartime—From the Spanish Civil War to Kosovo.” “Children’s art is so moving because it is so genuine,” says Geist. “While they may not be compositionally correct, they are emotionally true, and that’s what counts.” Geist firmly believes the children’s drawings are “historical documents, therapeutic documents, and works of art.”

“I think these are extremely important documents,” adds Geist: “It makes the news less abstract. We’ve been inured to tragedy. It’s in the headlines, it’s on TV, 24 hours on Fox News. This is a reminder that ‘collateral damage’ has a name and age and face. It’s 12 years old, and it draws these pictures.”

There will be a reception and a panel discussion with Olivier Bercault and Fred Abrahams of Human Rights Watch, UW professor Nancy Farwell from the African Studies department, and UW fellow from Sudan, Amna Ibrahim. 6:30 p.m. Wed., Feb. 1, Odegaard Library, UW Campus.