In the creative fields, gays are—how to put this?—well-represented, from theater to dance to Hollywood. That’s no less true in the art world, so a gay-centric museum exhibit would seem redundant. Still, that didn’t stop the Smithsonian from organizing Hide/Seek last year. It’s a group show now on its West Coast tour, and the rainbow roster includes heavyweight names like Eakins, O’Keeffe, Rauschenberg, Mapplethorpe, and Warhol. There are few up-and-comers here; the exhibit is presented more like a gay pantheon. Most of the artists are dead, some felled by AIDS, so the treatment is more somber than celebratory (no disco, no camp, no Glee). Instead of the usual Dead White Men who constitute the academy, we have mostly Dead White Gay Men (DWGM). If this is the secret sexual subtext to art history, now no longer secret, the show undersells the eros with its dry subtitle: “Difference and Desire in American Portraiture.” (Would it have killed them to try something sassier, like “Art on the Down-Low” or “Glitter-Bombing the Academy” or “150 Years of Art Fags”?)

It all sounds off-puttingly pedantic, until you actually enter the two main galleries where more than 90 works are displayed—mostly paintings and photos, plus a few videos. One chamber is postwar and the other historical, a distinction seemingly forced by architecture, not curators. (The Smithsonian’s David C. Ward and SUNY Buffalo’s Jonathan D. Katz made the original selection.) If you circulate along the intended old/new path, it’s possible to construct a happy historical progression from Walt Whitman’s 19th-century freedom to the closet (and its codes) to Stonewall and AIDS and, finally, gay marriage. The problem with this kind of up-from-slavery reading of the art, as the DWGM might tell you, is that their lives and circumstances weren’t so simple. Was Andy Warhol more or less free, more or less tormented, than Thomas Eakins? Which man put more of himself into his art, imbued it with more longing or less sex?

The very first painting to greet you is by Eakins, that great student of the male form, depicting a buff boxer offering a victory salute to his admiring fans. The large 1898 Salutat isn’t overtly erotic, but the half-naked athlete’s ass faces us. This is the image that invites you in, and its placement is no accident. So why not group it with other nudes and figure studies from different eras? Sorry, this is an historical survey, so you’ve got to circle through unrelated works by Berenice Abbott, John Singer Sargent, Cecil Beaton, Grant Wood, and other staples of the prewar era.

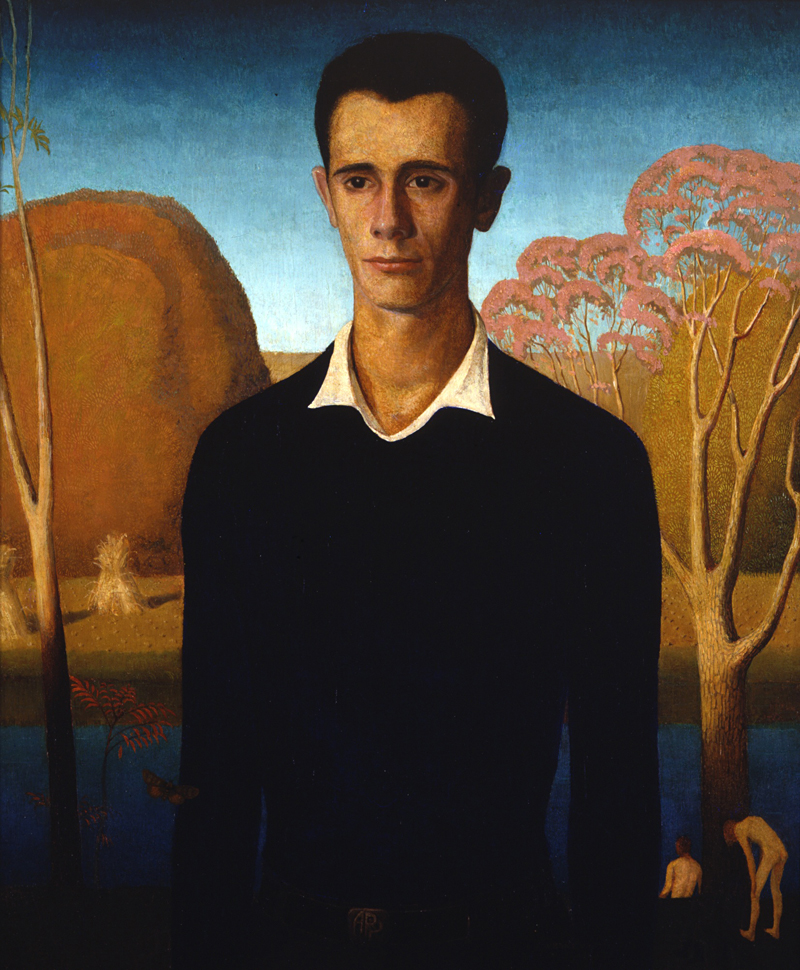

Among the familiar images from this period, Wood’s 1930 Arnold Comes of Age is impossible to see now as anything but a screaming case of repression. Prim, prissy, V-necked Arnold turns away from some nude male bathers in—what? Disgust, longing, self-disgust, fear, or Protestant self-denial? Lips pursed, hair neatly combed, he’s both pitiable and ridiculous. There’s a Midwestern sadness to his not getting what he (presumably) wants in life, but are all “liberated” gay men truly happy today? I’d like to see the painting paired with one of Robert Mapplethorpe’s bullwhip-up-the-butt photos (only his tamer stuff is included in Hide/Seek), since those S&M images have never seemed particularly joyful to me. Gay or straight, we just move through the centuries from one form of constraint to the next. From gay marriage comes gay divorce; from the right to adopt, ungrateful children who expect college tuition. Even if the priapic hero of the recent film Shame was hetero, the emptiness of his sexual license must resonate in the bathhouses. You’d like to tell poor Arnold that it gets better, but the more complicated truth is that you only exchange one set of problems for another.

In the postwar room, Warhol dominates, to an almost unfair degree. Beside an enormous late-career self-portrait and two video banks of his Factory screen tests, the huge 1962 Troy Diptych overwhelms you with the pretty mug of B-movie actor Troy Donahue (not to be confused with Tab Hunter, but both of them Hollywood products all the same). The silk-screened multiples are as familiar as Marilyn, Liz, or Campbell’s Soup; there’s the same bright machine-age melancholy to these assembly-line iterations. Stripped of personality (if he had one), not talented or famous enough to be well-remembered, Troy becomes an empty vessel—not unlike Arnold, above—who can take on any meaning. Closeted gay? Warhol’s guilty crush? An emblem of sheer, dumb sex appeal? It hardly matters which is true today: Troy is dead and his blue-eyed ’50s glamour now but a yellowed scrapbook memory, because beauty always fades.

Look over at William S. Burroughs’ photo of handsome young Allen Ginsberg (in 1953, on an East Village rooftop), and there’s the same mortal tug. Ginsberg has annotated the photo as if in a diary, to fix it in time. (His rent? $30 a month!) But art is never fixed in time. Only artists live (and die) in discreet chronological chapters. We go back and reevaluate their creations all the time, put them in new shows, new contexts.

Here, no matter the amount of interesting art to see, the problem is the context. Is it helpful to assess an abstract painting by Jasper Johns when set near a David Wojnarowicz video? Does the Mapplethorpe illuminate the Robert Rauschenberg? Hide/Seek means well, but it’s inherently reductive. The show doesn’t exactly create a Fire Island ghetto of gay artists; rather, it subordinates individual achievement to group identity. I’d much rather see a Warhol show, a Minor White show, a Marsden Hartley show than a greatest-gay-hits sampler such as this. This is especially true of the younger and (to me) less-branded artists like Cass Bird; I’d prefer more of her large color photographs of strangers to familiar images of famous gay icons (Whitman, Susan Sontag, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Langston Hughes, etc.).

And if you’re going to let Annie Leibovitz in the door (shooting Ellen DeGeneres), why not Tom of Finland?