Are you between shows? This is the question Eric Fredericksen, gallery director at Western Bridge, expects to hear a lot this summer. The current exhibit, Box With the Sound of Its Own Making—named for a Robert Morris sculpture owned by the Seattle Art Museum (though not currently on display there)—leaves most of the 10,000-square-foot gallery space empty.

Created in 1961, with an eye to Duchamp, Morris’ conceptual piece is more about the thinking it inspires than about the object itself. He recorded the sound of himself constructing a wooden box, then sealed the audio tape inside the finished piece. At Western Bridge, six male artists—Bruce Nauman, Jason Dodge, Ryan Gander, Jonathan Monk, and brothers Eli Hansen and Oscar Tuazon—riff on the idea of a piece of art being about itself. Most of the work in this sparely hung group show is thought-provoking, while a few pieces fall flat.

Minimalism takes the lead here. The gallery is mostly bare, and as a result you’re forced to hunt for the art. You might not know it when you see it. That, too, is part of the fun.

The most striking piece challenges you to ruin the central gallery. A length of bare copper pipe lies on the floor, with a small, red sign attached to it that says “BUILD A GREAT AQUARIUM.” The pipe is visibly connected to the gallery’s water main, many, many long feet away, so a turn of the valve will release water into the gallery. It’s a dare. This is Berlin artist Jason Dodge’s your death. Art collectors Bill and Ruth True, who own Western Bridge and use it to show work from their collection, are offering visitors a chance to flood the place.

Artist Jason Hirata, who was sitting at the gallery on a recent Saturday, says the water has been turned on at least three times. Joe Park, whose paintings are often shown by the Trues, was one of the culprits. “The pipe banged down really loudly,” Hirata recalled, “as there’s a lot of pressure there, and made a spray against the wall.” Hirata then cranks the handle himself slightly, causing water to hiss out and leave a dribbled puddle on the bare cement floor, which is marked with seams and stained from years of use by a construction company.

Follow the pipe back to the water supply, and you’ll find a gorgeous, burly tangle of muscular steel pipes, connected with circular handles and gleaming brass fixtures. Follow the circuit, and you’ll see the mess leads to a sprinkler system. The brand: Silent Knight. (This is actually more threatening. There’s a sprinkler system, ready, meant to douse the art?)

Dodge’s second piece, a current (electric) through (A) tuning fork and light, is rigged to the power supply. It’s a light fixture, with (as the name suggests) a tuning fork spliced into the wiring. The light bulb, clipped close to the high ceiling, is on, lit by a current that travels through the metal tuning fork. This too offers a challenge, as the bare wire and tuning fork are at about head height, the risk of electrocution within easy grasp. We’re not supposed to touch the art anyway, but you can’t help but wonder: Will doing so in this case actually kill me?

In both cases, however, the edge has been taken off. There’s a safety valve connected to your death that cuts off the water supply. And a current has been specially wired with low voltage, Hirata tells me, so it won’t cause any harm. After anticipating a charge, even craving a small jolt, feeling nothing is a disappointment.

Also deflating, in a provocative way, are Dodge’s series of flat grey sheets of undeveloped photo paper exposed at sunrise at various spots on the globe, all taken on the vernal equinox in 2006. The idea, and the names of the places—Nuuk, Greenland; Minneapolis; Shanghai; Mombasa, Kenya; Monaco; Warsaw; Vilnius, Lithuania; and Randers, Denmark—are romantic, but the muddy pages are not. Each sheet is the same dull tone, no matter where it’s from. The untreated photo paper is contained in transparent Plexi boxes, which means that the light captured from all these far-off cities is being mixed with Seattle light. The series is titled Into Black, which is just what will happen to these sheets as they keep absorbing more light.

Are tourist photographs this boring? Is the idea of captured light this romantic? And does romance necessarily have to be disappointing? What do you want to see in these frames? And how could eight people in such disparate places all get the same bland thing? This series works to probe and trouble you with these questions.

Bruce Nauman, best known for his work in neon, is the show’s biggest name. And you might, on first look, take the piece in the small side gallery, A Phantom of Appropriation, for his. It’s not—though Ryan Gander’s nod to Nauman is a big one. This London-based artist’s neon piece is broken, with red, blue, green, and white glass littering the floor, but the wiring is intact, and the whole shattered mess is plugged into an outlet: Again the potential is essential.

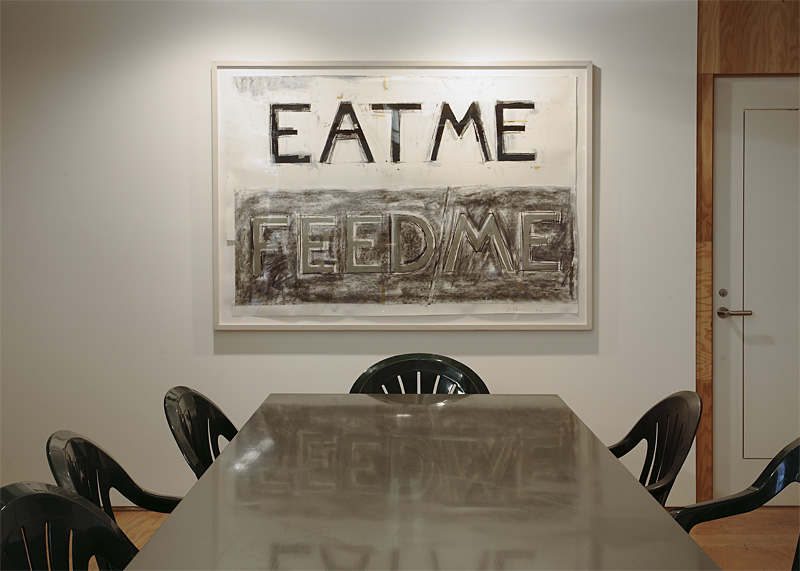

Western Bridge has a residency space on the second floor, where visiting artists sometimes stay, with an open living room and kitchen, as well as a small bedroom, all open to the public during gallery hours. This is where several of Nauman’s lithographs hang, as well as his monochrome mixed-media piece, Eat Me/Feed Me, in oil stick, graphite, and charcoal.

Eat Me/Feed Me (1990) is loose and gestural, with fat markings composing the hungry text. It’s hung at the end of the long dining table. Stepping back to view it, you might notice that the table legs stop short of the floor. The table is instead supported by a central, mirrored column, while its legs are merely for show. The furniture, like the space itself, was designed by artist/architect/designer Roy McMakin. His steel versions of the ubiquitous green plastic lawn chair sit outside at the Olympic Sculpture Park. Here, at the table, several of McMakin’s heavy steel chairs (also green) are next to their plastic twins. You’ll have to touch the chairs to know which is which.

Outside in the parking lot is what looks like a forgotten bit of construction, a rusty-beamed structure set atop a cement pad. It resembles an unfinished contraption you might stumble across in the woods. Installed by brothers Eli Hansen (of Tacoma, whose solo show just concluded at Lawrimore Project) and Oscar Tuazon (currently in Paris), this bare-bones sculpture, Use It For What It’s Used For, speaks to the pairs’ rural upbringing and their penchant for abandoned utopias. It’s rigged to a solar panel that powers an overhead fluorescent light fixture. Connected to a sensor, the light will turn on when the sun goes down.

This piece, unlike the rest of the show, will remain onsite for two years, and one can only wonder what use it will see (besides drinking, on opening night). In New York City, where it was installed last year, the piece was locked inside a fence, so it could be seen but not occupied at night. Here, one can imagine urban camping, beer cans strewn about, the detritus of a sloppy party.

This quiet exhibit—and there’s more, including a nearly hour-long video of Nauman’s desk at night, two large photographs by Gander that show white sheets of paper suspended from strings in his studio, and a neon work by Berlin artist Jonathan Monk—is an installation in the best sense: The art makes you take a closer look at its surroundings, at the objects not usually thought of as art, and at your thinking as well. You might appreciate the mottled beauty of a cement floor, the power of an industrial-strength water system, and the threat of a live wire. One wonders what happens at Nauman’s darkened desk, and what might happen in the parking lot?