When Tim Rollins, a 26-year-old graduate of Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts, came to the South Bronx in the 1980s to teach teenagers art, he brought a healthy ego and high ambition. “Today we are going to make art,” he told his students, “but we are also going to make history.” His tough-love instruction was controversial but successful. And he’s gotten high marks in the art world: The sophisticated conceptual works made over the course of 25 years by his so-called “Kids of Survival” have been exhibited by some of the most important venues in the world, from the Whitney to the Venice Biennale, and total sales have topped a million dollars.

Now they’re honored by a traveling show, Tim Rollins and K.O.S.: A History, which is in its final weeks at the Frye. Organized by the Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York, the show was brilliantly installed by Frye curator Robin Held. When you walk in, you first see a documentary film about the fascinating people and process behind the works. Then you glimpse, through a muslin wall, a long rectangular classroom table with books and art. Finally you come to the elegantly spare, MOMA-like galleries, and grasp how far the artists came from the streets to the works of scale and sophistication we associate with high culture.

Rollins, a white alcoholic’s son from rural Maine who remade himself by reading classic literature, introduced the mostly Hispanic Bronx kids to the wonderland of these books. He had them read aloud some of the ones he’d loved growing up, like The Red Badge of Courage and The Scarlet Letter. He and the K.O.S. enlarged pages, discussed imagery that might go with them, projected images onto the pages, and painted them.

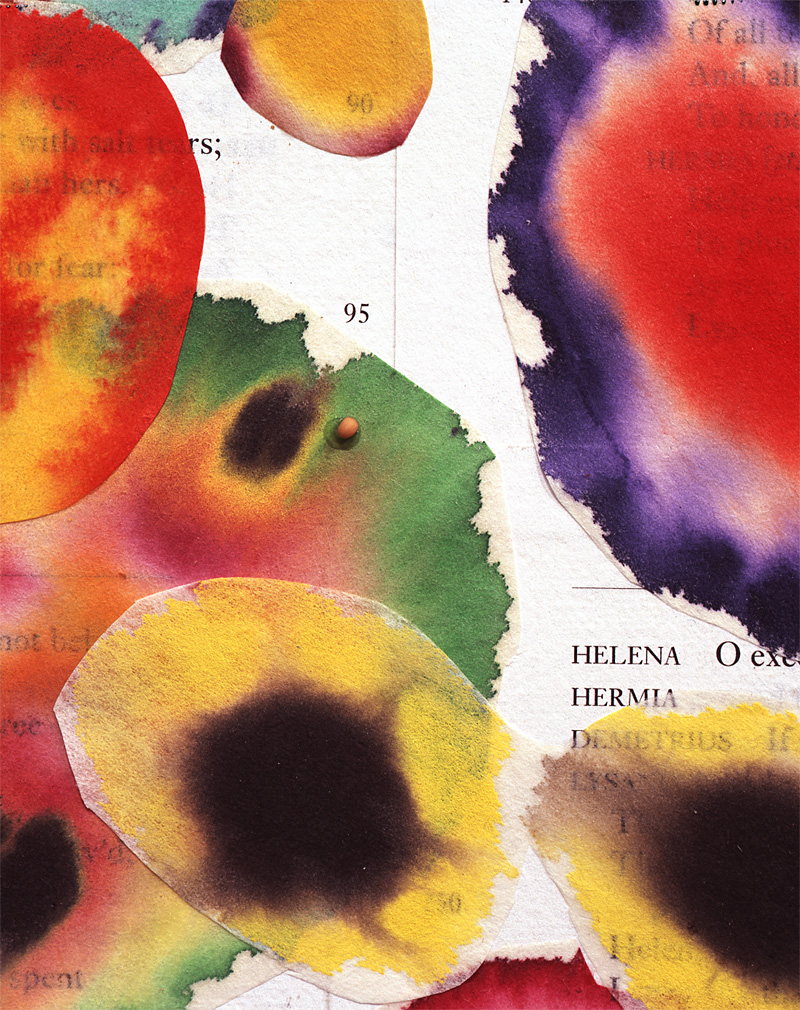

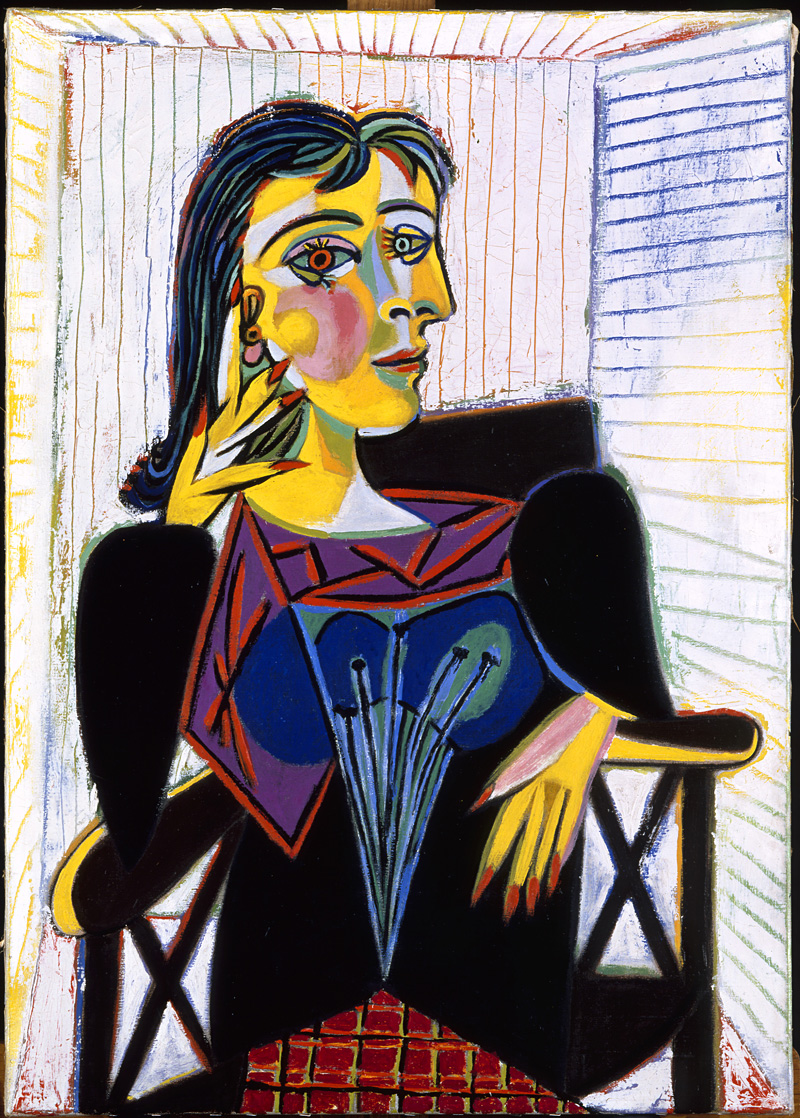

The lesson he conveyed is that abstract art can be a metaphor for emotions. You can make watercolor generative and flowing to suggest hopeful blooms, as seen in paintings based on A Midsummer Night’s Dream. (A detail from #6 in the series, created in 2000, is shown above. It also includes fruit juices and mustard seed.) Or you can make the paint bleed and pool in introspective rings, like the open wounds painted on pages from The Red Badge of Courage. Pulsing against the white skin of the text-lined canvas, some of these badges are more graphically rendered, geometrically patterned and hard-edged.

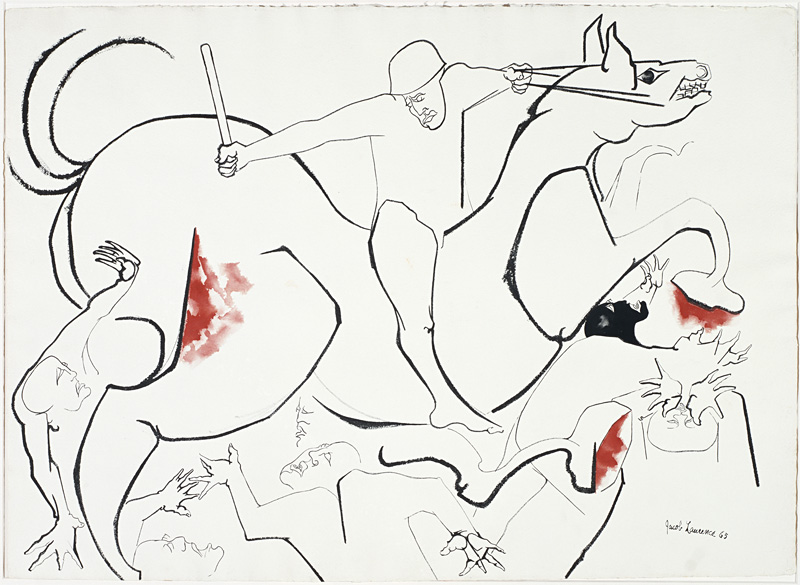

The kids’ greatest hit was a series of paintings influenced by Kafka’s novel Amerika, which describes women dressed as angels playing golden horns. The piece in the show is a nearly 6′ x 15′ canvas on which are painted the kids’ answers to the following question: “If you could be a golden instrument, if you could play a song of your freedom and dignity and your future and everything you feel about America and this country, what would your horn look like?” The horns they drew show precocious skill in traditional painting techniques of modeling and chiaroscuro, as well as the direct impact of graphic street culture. The biomorphic and architectonic shapes recall plumbing, human organs, and screaming mouths, intertwined in an ochre maze that almost obliterates the text, creating a fence of complex imagery. It’s a brass orchestra of abstraction, a resonant statement of identity.

Here’s the bottom line: The work is powerful. Rollins had kids make their own scarlet A’s for The Scarlet Letter; one looks rococo, another looks like metal rivets, another like a car’s hood ornament, another like a lock. To the kids, it was not just a response to Hawthorne or Rollins. Their A’s were a retort to what outsiders thought of the Bronx—a disgusting place from which only ugliness could ever come. Like Hester Prynne’s embroidered A, made lovely to defy society’s judgment, one of the Kids of Survival says in the film, “It is important for them to be beautiful.”

In this painting, the kids rule, though of course their work would never have been seen in the celebrity klieg lights of the art world without Rollins’ educated eye and ambition, his idealism, inspiration, and marketing genius. Some of the K.O.S. kids escaped their difficult upbringing to graduate from college, thanks in large measure to him. It helped that he was able to pick his all-star players, like an NBA talent-scout coach. He and they deserve their glory, but here’s to those unsung heroes in education and social work who labor daily with at-risk kids regardless of recognition.