IT’S EASY FOR the reader of a well- written personal memoir to imagine an intimate acquaintance with the author. It is therefore disconcerting when the picture that emerges from volume two of an autobiography is a good deal uglier than the portrait in volume one.

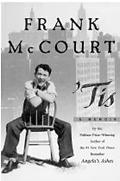

‘Tis: A Memoir by Frank McCourt (Scribner/Simon & Schuster, $26)

So it is with ‘Tis, the sequel to Frank McCourt’s 1996 debut memoir Angela’s Ashes, which was a hot best-seller, won a Pulitzer, and will soon be released as a Hollywood movie. Most readers of ‘Tis will come to it with expectations set high by the earlier work, which told the story of McCourt’s traumatic childhood. It seemed miraculous that the puckish, good-humored spirit narrating the book could have emerged from such a background. In the sequel, shadows invade that spirit.

Angela’s Ashes is set in a Limerick, Ireland, slum during the ’30s and ’40s. Though depicting crushing poverty and the most extravagantly cruel neglect, it manages to transcend these conditions with humor. McCourt jauntily mixes pathos and comedy in the voice of an innocent boy, whose ear for dialogue preserves the richly colorful use of language all around him—one of the few assets his childhood has to offer. Nevertheless, his bleak existence gets bleaker. His drunken, improvident father walks away. His family is evicted. Siblings die. Finally, McCourt escapes to America, a land that never looked more like paradise. There, in 1949, McCourt responds to the question “Isn’t this a great country altogether?” with the final celebratory word in the book: “‘Tis.”

And so McCourt’s sequel begins. The reader can be forgiven for expecting some celebration of life; ‘Tis recounts how McCourt overcame his humble start to become an immigrant success story as a teacher. His many years in the New York City public schools eventually lead him to one of the best, the prestigious Stuyvesant High School. Surely more humor is in store; but alas, it tastes sour on the tongue.

The same naﶥ voice that was so successful throughout Angela’s Ashes quickly grows grating when Frank grows up. Yet worse than this stylistic error is what fills his head. Instead of approaching his new opportunities in a spirit of hope or optimism, McCourt sinks into a bitter resentment at the privilege around him. He looks with a mix of yearning and disdain at the young WASP students who on weekends throng the lobby of the fancy hotel where he initially finds work. What do these spoiled rich kids do to earn his contempt? Why, the bastards have attractive, tanned bodies and good teeth; the girls radiate blonde American beauty and the boys a cool self-assurance. As McCourt senses he will never be one of them, his life—and this book— begin to be consumed with a debasing envy.

DRINKING IN AN upscale bar years later, McCourt is explicit about this chip on his shoulder. He shares his thoughts about the other customers, who have done nothing more terrible than engage him in some light banter: “I’d like to tell them to kiss my arse and if I had a few more drinks I would,” he writes, “but I knew that inside I’m still plucking at the forelock and shuffling my feet in the presence of superior people.” This paralyzing attitude is not more attractive for being openly expressed.

It would be bad enough if McCourt’s pathetic self-image hurt only himself. However, in this, his own account, the man whose childhood story aroused vicarious compassion in his readers shows little for anyone else. As if McCourt is being cruel to himself, displaying his own coldness with brutal honesty, the story that he tells indirectly discloses the neediness of many whose paths cross his, while the narrator passes glibly over those needs, entirely wrapped up in his own petty frustrations.

The saddest part of the book is the description of McCourt’s first marriage. Partly by trading on his colorfully humble past, he manages to win the heart of one of those attractive WASP blondes of whom he had earlier been so contemptuous. Predictably, perhaps, he treats her badly. The unfortunate young woman is from a comfortable, middle-class New England background—and McCourt cannot forgive her that. She suffers an emotional roller-coaster ride that careens between his desire and his rejection, aggravated by his regular drunkenness.

What is clear at the end of ‘Tis—something readers couldn’t have gathered from Angela’s Ashes—is that McCourt did not, after all, walk away from the slum unscathed by impoverishment and his father’s alcoholism. For those of us who had foolishly imagined otherwise, this portrait that fills the gap between the boy victim and the successful author brings us back to earth.

By the time McCourt attempts to pass off his eventual divorce with a casual “Slum-reared Irish Catholics have nothing in common with nice girls from New England,” he has long passed the point of any sympathy. One can only cheer his wife when she turns on him. “Stop the whining,” she shouts, “I’ve had enough about you and your miserable childhood. You’re not the only one.”

Dominic Gates was born in County Tyrone, Ireland. He lives in Seattle.