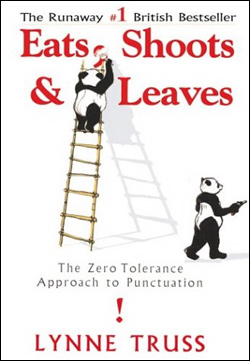

Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation By Lynne Truss (Gotham, $17.50)

The shelves of almost every London bookstore were chock-full of this how-to grammar book, a No. 1 best seller in England, when I was visiting the U.K. this past January. I fantasized about seeing it in the same position on The New York Times best-seller list, perhaps knocking off the army of low-carb diet guides. How could a book about punctuation be so popular? This could mean three things: The book- buying population in England is full of spods (British for dorks); British people are more honest about admitting ignorance in the grammar department; or Lynne Truss actually makes it entertaining to read about commas and semicolons.

Probably all three are true. But for myself, being both a spod and grammar aficionado, I was also enthralled by the author’s fascinating historical account of punctuation itself. Indeed, her enthusiasm is so ebullient that when Truss describes the Venetian printer Aldus Manutius the Elder, the man who invented italics and first printed the semicolon, she exclaims in a Bridget Jones tone, “I will happily admit I hadn’t heard of him until a year ago, but am now absolutely kicking myself that I never volunteered to have his babies.”

Did anyone observe the missing apostrophe from the Sandra Bullock–Hugh Grant movie Two Weeks Notice? Truss did, along with the rest of her fellow “sticklers” who feel the sharp sting of a bee when apostrophes are blatantly abused. With examples like Two Weeks, Truss explains the rules of grammar with everyday instances, breaking down each rule for even the most grammar-phobic among us.

Had an index been compiled for this slim, useful book, I would’ve kept it on the shelf of invaluables next to my Strunk & White, Chicago Manual of Style, and William Zinsser. SAMANTHA STOREY

Lynne Truss will appear at University Book Store, 7 p.m. Mon., April 26.

The Perfect Mile: Three Athletes, One Goal, and Less Than Four Minutes to Achieve It By Neal Bascomb (Houghton Mifflin, $24)

It’s all about the circular sweep of the second hand in the stopwatch—not today’s wrist-worn digital kind, but the heavy, satisfying mechanical models seen dangling around the necks of fat-bellied track coaches in yellowed old newspaper clippings. The fact that it takes four revolutions of a 440-yard track to cover a mile and four revolutions of a stopwatch to clock four minutes is why the date May 6, 1954, is historic. The happy homology of it, the perfect echo of each 60-second lap around the cinders within the smaller sphere of the stopwatch, is why Roger Bannister is remembered on the 50th anniversary of his feat—becoming the first man to break the four-minute barrier—and why author Neal Bascomb has trotted out a new book on the subject.

Actually, it’s an old subject, and an old story already told several times before. It’s also been told better (notably by physician Bannister himself in his 1955 The Four-Minute Mile, reissued in paper 10 years ago), without the unwieldy three-man, three-story structure Bascomb invents as a hokey narrative device—presumably to make it more American-friendly and movie-friendly. Indeed, the movie rights to Perfect have already been sold to the producers of Seabiscuit. That’s not a good sign, since they took a good book and made it into a burnished, boring, mediocre Oscar nominee. Here, although three handsome young actors will be able to star instead of a nontalking horse, the entire tripartite structure leads to a climax in which one of the athletes—the American, no less—isn’t even competing.

Brit Bannister and Aussie John Landy actually met and competed against each other, most famously at the August 1954 Commonwealth Games in Vancouver, B.C., when both bested the four-minute standard again. But Kansan Wes Santee, though he had a good chance to crack four first, is pretty much a historical footnote to Bannister’s story—one that Bascomb unwisely inflates for the domestic market.

The current record, held by Moroccan Hicham El Guerrouj, is 3:43.13, not a number with much poetry to it; a shorter 1,500-meter distance is now the world standard on 400-meter tracks—all that beautiful symmetry is lost. Sub-four-minute miles are no longer rare, although good writing on distance running still is. Bascomb falls short of the standard of, say, Sports Illustrated‘s Kenny Moore, but the wildly different personalities and circumstances do come through in the three runners he profiles here. His book is well researched and well told enough to get optioned. To play Bannister, however, Hugh Grant will have to lose some weight. BRIAN MILLER

Neal Bascomb will appear at Seattle Running Co. (919 E. Pine St., 206-634-3400), 7 p.m. Tues., April 27.

Sun After Dark: Flights Into the Foreign By Pico Iyer (Knopf, $22.95)

“The excitement of travel,” writes Pico Iyer in this collection of essays on far-flung destinations, “is that you’re in a place where nothing makes more sense than a dream.” And there’s nothing like traveling alone to make you doubt your sanity: I once awoke in a guest house in Laos in a fit of paranoia, convinced everyone was trying to prevent me from attending a festival the next day. Travel does weird stuff to you, and that’s its power.

Hallucinatory and observant, this little book confirms Iyer as one of the most gifted wanderers writing today. Devoted Iyer followers might be disappointed at what is essentially a repackaging of essays and magazine pieces from the past five years, but a narrative thread holds the project together. I hesitate to call this a spiritual travel book (a squishy genre in which spoiled First World–ers seek solace in the problems of the Third World). And yet spirits and spookiness and weirdness are exactly what Iyer stumbles into repeatedly.

Whether he’s reading the works of the late German author W.G. Sebald or chatting with a magelike Leonard Cohen at a Zen retreat, Iyer everywhere finds the world beautifully disoriented: by cultural globalization; by our hybrid English language; by the fact that once-distant Lhasa, a place that before 1979 had seen a total of just 2,000 Westerners, can now be reached within 24 hours on a moment’s notice.

But it’s when the author’s lost in the streets of Manila or La Paz that his work takes flight from merely unfamiliar terrain into unreality itself. Who was that mysterious stranger who always knows of his arrival on Bali? What exactly was that temple in Tibet whose existence he could never confirm in any guidebook? Did an ill-advised tour of a prison in Bolivia really turn into a small nightmare out of Kafka? These are the necessary confusions of travel—which, for Iyer, pop open the emergency exits of perception. Under the fog of jet lag, he writes, “another city comes forward, as if the 21st-century construct were peeled away to reveal something more odorous and ancient, less domesticated.”

If this all sounds a bit woo-woo, it’s not—Iyer grounds all of his book in lovely reporting. The one disappointment in Sun is that he parcels himself out in rather meager helpings. But his book confirms that travel, even in the era of terrorist fears, is still the best way to experience the true strangeness of the world. ANDREW ENGELSON

Pico Iyer w ill appear at Elliott Bay Book Co., 7:30 p.m. Tues., April 27.

Strangely Like War: The Global Assault on Forests By Derrick Jensen and George Draffan (Chelsea Green, $15)

The title of this impassioned, sometimes-eloquent tract is taken from Murray Morgan’s 1955 classic, The Last Wilderness, which recounts how the early timber operators on the Olympic Peninsula “attacked the forest as if it were an enemy to be pushed back from the beachheads, driven into the hills, broken into patches, and wiped out.” Then, Morgan could muse wryly; writing today, after 75 percent of the world’s and 95 percent of the United States’ original forests have been cut, Derrick Jensen and George Draffan don’t allow themselves that luxury. Theirs is an angry book, but their fury is directed at a worthy target, and they come by it honestly.

As activists here and in Northern California, the authors have bashed their heads against the obdurate determination of the pulp and timber companies to cut the last tree and of federal forest caretakers (many of them timber-industry crossovers) to abet them. The first and better half of War is largely an account of those battles and of the Byzantine web of corrupt pseudo- science, official complacency, and green-wash propaganda that subverts regulation, wears down opposition, and enables the conversion of richly self-sustaining forests into monocultural fiber plantations.

In the second half of their brief (143-page) text, Jensen and Draffan go global at a gallop. They pack in a (literally) breathtaking assemblage of statistics and horror stories—of ecosystems wrecked; of apes and tigers exterminated in the relentless pursuit of cheap toilet paper and chipboard; of vast tax-subsidized profits for wood and pulp multinationals; of indigenous communities bought out, sold out, moved out, overrun, or simply murdered, from Guatemala to Amazonia to Burma to Sarawak. Drawing on many sources, such a wide-angle scan can inevitably seem secondhand, and some sourcings may be suspect. One hair-raising story, about a Philippine timber cop who actually tried to do his job and, as a result, had to shoot it out with his bosses and serve a life sentence for murder, is credited only to the “Earth Liberation Prisoniers” (sic) Web site. Two SW articles (not mine) also figure prominently; take that as you will.

The authors also cite more venerable sources: Abraham Lincoln on the “enthronement” of corporations, concentration of wealth, and looming “corruption in high places”; Plato’s Critias on the razing of Greece’s forests and the washing away of its formerly “fat and soft earth”; and the Babylonian hero Gilgamesh, the patron saint of all deforesters, who kills the forest guardian Humbaba and brings down a curse that has “followed us now for several thousand years.” Weaving together ancient warnings and the latest data, Jensen and Draffan describe industrialization, globalization, and civilization itself as essentially a process of deforestation that is now approaching its self-consuming end. You may wince at some of their anti-globalist hectoring and find their prescription—a devolution of power to local control—plaintively wishful. They do, too, but you gotta try. And you could hardly ask for a punchier, pithier diagnosis of an illness that’s as big as the planet and as close as the nearest clear-cut. ERIC SCIGLIANO