There are only a handful of Northwest companies with a national reputation, few of which are named for their founders. Nordstrom, Boeing, and Weyerhaeuser are the exceptions. In a generation or two, Microsoft, Starbucks, and Amazon will have different identities than the men who established them. A successful brand must necessarily outlive its founders, which is why not all of us can name the graybeards pictured in old company histories and annual reports. Some CEOs refuse to retire and die in office, like Edison and Jobs. Others gradually step away, like Gates and Allen. On a smaller cultural scale, Sub Pop’s Bruce Pavitt departed 17 years ago, while Jonathan Poneman has recently been slowed by Parkinson’s. The baby boomers are inevitably fading, and succession must be considered.

That’s the situation for another iconic Seattle company, Fantagraphics, whose vice president and co-publisher Kim Thompson died of lung cancer in June, after more than three decades of partnership with company president Gary Groth. Since moving their business to Seattle in 1989, the two men built a niche publishing empire, transforming comics from pulp to prestige. The company is now Groth’s alone to run.

How has Fantagraphics evolved over the decades? Says Groth, “If I could distill my goal in, say, the early ’80s into one that is more coherent than it actually was, it would be that I wanted to see the perception of comics among the general public as nothing but superheroes and their ilk recede, and a readership for artistically ambitious comics to grow. In retrospect, that was a fantasy, of course, and what eventually happened was far messier.”

Fantagraphics was founded in 1976 to launch The Comics Journal, a very opinionated annal of the trade that made Groth and Thompson high-profile critics of their industry. As both editors and writers for the Journal, the two young men had an outsize impact on a moribund business, often disrespecting their elders and picking up many enemies along the way.

Then in 1981, Fantagraphics joined the industry it so often criticized. The gadflies became insiders. How did that happen? “It was partly happenstance, partly a logical progression,” says Groth. “The Comics Journal was championing a vague but real aesthetic direction for comics, and we slowly realized we could put those theories into practice. The Hernandez brothers’ self-published Love & Rockets was a revelation because it suggested what I had envisioned, in my mind’s eye, the kind of comics I wanted to see. Little did I know that they would mature and in short order create work that was almost the embodiment of what I had hoped to see.”

While continuing with the Journal, Fantagraphics gradually added famous—or soon-to-be-famous—names to its roster. These would grow to include Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, R. Crumb, Joe Sacco, Chris Ware, and Dan Clowes, along with locals like Jim Woodring, Peter Bagge, and Ellen Forney. But the company didn’t really gain momentum until after moving to Seattle.

And how exactly did that move come about? “I wanted to get the fuck out of L.A., which was too expensive and culturally derelict,” says Groth. “Pete Bagge, who was living here at the time, talked up Seattle; I visited for the first time, took a tour with Pete and his wife Joanne, and liked the vibes. I flew back to L.A. and announced we were moving.”

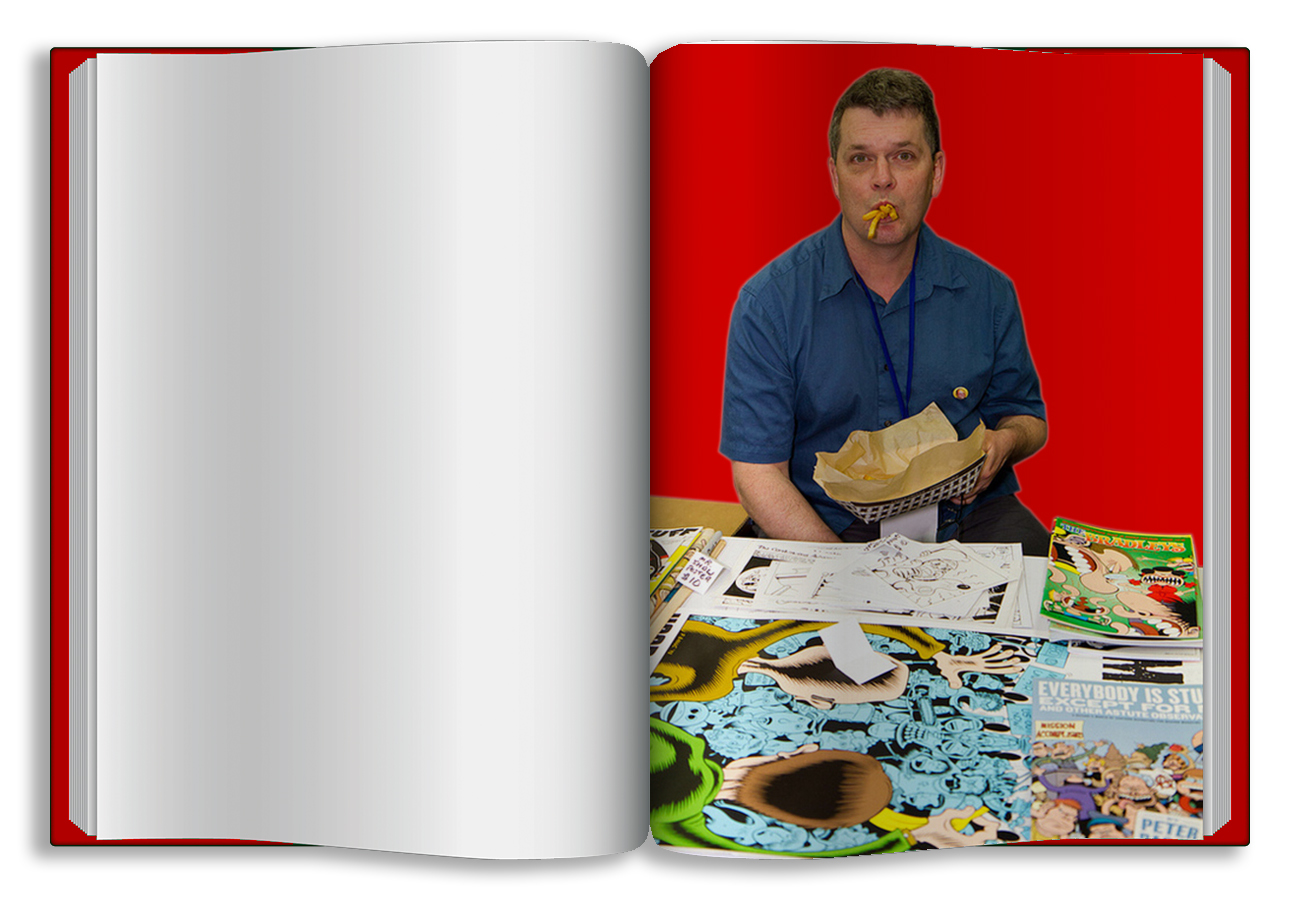

That move turned out to be extraordinary well-timed, says Larry Reid, the longtime Seattle art-world curator and promoter who now runs the Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery in Georgetown. “I was a voracious consumer when Fantagraphics moved here,” he recalls. “Peter [Bagge] had a party for them at his house, and I immediately pestered Gary and Kim to have a comics show at the Center on Contemporary Art.”

Two years later that show became Misfit Lit, Fantagraphics published the catalog, and Reid took it on tour around the country—all of which helped cement the grunge/comics/Seattle alliance in the national consciousness. “Music, graphics, and comics all came together” in the early ’90s, says Reid. From that convergence, Fantagraphics “became a part of our cultural heritage.”

That heritage will be celebrated at Bumbershoot this weekend at an event called the Fantagraphics Follies, convened and hosted by Reid. Rather than have artists simply talk their way through PowerPoint presentations, he says, “I wanted to do something more entertaining, to mimic the form of a TV talk show. We’re going to have a couch and a desk and a bandstand.”

To that end, with Bagge’s rock group Can You Imagine? performing as house band and Reid serving as Lettermanesque host, guests will include Woodring, Forney, Eroyn Franklin, Kelly Froh, and Danny Bland. Franklin will perform a shadow-puppet show. Woodring will be wielding a giant 7-foot pen to create a work on the floor. And Froh will perform “something more akin to stand-up comedy,” says Reid. Bland, whose forthcoming Fantagraphics novel (not a graphic novel) In Case We Die is based on his grunge-era experiences, will read beatnik-style while Steve Fisk plays piano. (The pairing is an homage to Jack Kerouac reading On the Road to Steve Allen’s piano.) Music producer Fisk, famed for his work with Nirvana, Soundgarden, and other groups, also plays with Bagge’s band.

By an accident of timing, Reid admits, this Fantagraphics celebration is tinged by Thompson’s death, still mourned within Seattle’s tightknit comics community. “There’s no replacing Kim,” says Reid. “He was my boss, but more important, he was my friend and colleague. He lent a degree of sophistication to the whole line.”

Forney, who moved to Seattle largely because of Fantagraphics’ presence here, shares the sentiment. “Kim’s death has affected a lot of us here. Kim was much more behind-the-scenes [than Groth]. But artists knew who he was. He was a major part of Fantagraphics. I miss him terribly.”

Still, after the tears are shed, books still have to be printed and sold. Business is business, and Groth is looking forward. “Over the last decade, Kim spent more and more of his time working on European books,” he says. “So the most concrete and tangible consequence of his death will be to cut back—but by no means eliminate—our European line. We will continue publishing a number of authors, including Jacques Tardi, Jason, and many artists of the following generation [such as Uli Lust].”

Beyond that, Groth is mostly mute on the state of his company, declining to answer many questions on its place in a fast-changing industry. The Internet, Kindle, and iPad have profoundly altered the economics of publishing over the past decade. In response, Fantagraphics has a sophisticated website that encourages interaction with readers. And its Georgetown bookstore, which opened in 2006, gives the company a bricks-and-mortar presence at a time when many traditional book retailers are closing.

Groth appears unruffled by such market changes. He notes that the company is venturing beyond comics, writing that “Over the last five years, we’ve published a number of prose novels by a variety of writers, some established, some new—Alexander Theroux, Stephen Dixon, Danny Bland, and Monte Schulz. We recently published Kipp Friedman’s memoir, Barracuda in the Attic; and next year we’ll be publishing a history of 20th-century comedy by Ben Schwartz. Last year, we published The Last Vispo, a collection of Visual Poetry, as well as Pat Thomas’ Listen, Whitey, a coffee-table book tracking the intersection between pop culture and the black-power movement.”

While Fantagraphics is offering some titles in digital format, handsome hardbound reissues of the classics—Charles Schulz, Mickey Mouse, Steve Ditko, Donald Duck, etc.—have been instrumental to the company’s survival. Costing up to $50, such volumes are priced for collectors, not kids, but that speaks to the baby-boomer nostalgia market. It’s a far cry from comics’ pulpy old origins. The industry has matured, in no small part owing to Fantagraphics—once a ’70s upstart, now an established Seattle company.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

Fantagraphics Follies plays Saturday at 6 p.m. at the Seattle Rep.