In a kind of kitchen-sink psychobabble that eerily imitates the tone of the play itself, Theater Schmeater’s press release describes Bug as a “tense comedic psychological horror play.” That’s putting it lightly. Tracy Letts’ play indulges in a highly specialized brand of paranoia, the sort of itchy, twitchy, drug-addled manic state that brings to mind the lonely, hellish journeys mapped writers like Hubert Selby, William Burroughs, and Philip K. Dick. Set entirely in a seedy, muggy hotel room somewhere outside Oklahoma City—a symbol of explosive paranoia if ever there was one—Bug depicts a micro-universe in the process of shrinking to a pinpoint of abject terror. The ultimate source of that terror is a grand conspiracy, which may or may not be true, involving the possible subterfuge of the military-industrial establishment.

Bug, therefore, plays that most iffy of fictional games: to show what insanity looks and feels like—to capture from the outside the tenor and texture of such an intensely inner experience—while also questioning the fragile, fractured nature of modern reality itself. Is that whirring of the chopper blades offstage just a hallucination? And if so, what isn’t a hallucination? Talented director Carol Roscoe partly solves this conundrum by creating a hermetic environment of such high-velocity craziness that there isn’t time to reason through the finer points of the play’s conspiracy theory.

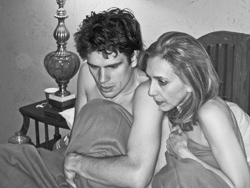

Trapped inside this bugged-out vortex are a pair of unlikely and unlucky lovers: Agnes White (Marty Mukhalian), a beat-up, broken-down woman given to red wine and hiding from her abusive, ex-con ex-husband, Jerry Goss (Jim Lapan); and Peter Evans (Colin Byrne), a mysterious, initially taciturn Gulf War vet who slowly reveals a deeply disturbing belief that he has been the victim of a gruesome, X-Files type of military experiment. In many ways, these two tragic cases engage in a familiar dance of mutual and self-destruction; like any number of fictional pairings before them, they create a sealed, self-perpetuating vacuum of need and anxiety fed equally by lust and fear. As Peter reveals the various symptoms of his disease—aphid bites, egg sacs deposited in his feet—Agnes becomes more and more involved in his crazy drama, which is compounded by other strange signs (those whirring helicopter blades, for one). Add Agnes’ gay friend R.C. (Angela DiMarco) and one Dr. Sweet (James Cowan), a bizarre figure who may or may not intend to help Peter, and what you have is one fucked-up stew of nth-degree paranoia and desperation. A sort of hostage situation ensues, though it’s difficult to determine exactly who is being held hostage and who is in control. The entire affair, pervaded by a sense of impending violence, slowly ratchets up to a terrible breaking point. Whether Peter’s delusions are true or not becomes somewhat irrelevant because the result will be the same either way: Someone’s going to get hurt. The question becomes who? And how?

Bug, with lots of nudity, edgy sexual situations, and an unflinching representation of the signs of the sickness that overwhelms Peter and Agnes, is not a play for the squeamish, prudish, or faint of heart. The whole environment of the play is dark and psychologically disturbed. Mukhalian and Byrne make a convincingly clinical pair of hard cases, even if there are moments when it’s a bit hard to grasp the exact nature of their connection beyond the whirlwind of insanity that sweeps them along. DiMarco, Cowan, and Lapan are all strong in supporting roles—especially DiMarco, whose solicitous demeanor works occasionally to ground the proceedings in necessary reality. At times, Bug threatens to degenerate into pure spectacle, a parade of shock and awe, though for the most part, director Roscoe keeps things on a dramatically even keel. Letts’ play (the film version of which also opened last Friday) is a risky and dangerous work, and if only for that it would be worth a look. As usual, Schmeater, true to tradition, treats this kind of challenging and vaguely political material with the respect it deserves. It’s hard to imagine anyone in town doing a better job.