The rise of digital streaming has proved a bonanza for fans of adventurous, wide-ranging entertainment. But for most of the artists whose work is being streamed, it’s been an unmitigated disaster. Royalty payments to originating performers for streaming use are a tiny percentage of the fees they used to get for CD and DVD sales or even by-the-cut downloads.

You’d think streamed classical material wouldn’t have that downside. After all, most of the originating artists have been dead for centuries. But many of the same conditions do apply: for users, phenomenal access to a range of material undreamed of only a decade ago; for performers, a pittance per view, if that.

Anybody who uses YouTube knows that if cat videos are your thing, you’ve found your Internet sweet spot. But much the same thing applies to fans of “high art,” like opera, ballet, and chamber music. Poke just below the surface on YouTube, and you’ll find gems like Giuseppe Verdi’s utterly obscure masterpiece Aroldo, complete, in a blazing 2003 live performance from Piacenza’s Municipal Theater in Italy. The same show will set you back over $20 on DVD. And most of YouTube’s free bounty isn’t available at all in other media. There’s a lot of dross, of course; but plenty of gold amid the gravel.

Some major art producers are giving away their best. A remarkable example is the Bavarian State Opera, now in its second season of presenting free streamed live performances of five operas (and two ballet evenings), including rarities like Richard Strauss’ The Silent Woman and Janaček’s The Makropulos Affair. You never know where the lightning’s going to strike: Check out The Guardian’s home page and Rameau’s gorgeous Hippolytus and Aricia pops out at you, filmed at Glyndebourne last summer.

Most top arts presenters aren’t so generous. If you want to watch and listen regularly to the sleek Berlin Philharmonic, for example, be prepared to pony up 20 euros (about $25) a month to tune into the orchestra’s “digital concert hall.”

Yet there are options just as classy that offer a wider repertory at more modest cost. About the glossiest streaming-arts collection is Great Britain’s Digital Theatre, which offers prestigious productions from the Royal Opera and Royal Ballet alongside top stagings from the Royal Shakespeare Company, Young Vic, and London’s star-bedizened West End theater scene, all for as little as $6.50 a show.

Paris-based medici.tv pioneered this all-the-arts model in monthly and annual subscriptions that range from $12 to $150. From a modest start, the company now presents top events like the Salzburg Festival and Bolshoi Ballet premieres.

You will have noticed that the presenters listed so far are all European. The only U.S. organization with similar ambitions is the Metropolitan Opera, which packages its huge library of Met Opera in HD performances in annual subscription form for $150 a year, less for the Met’s “supporting” contributors. (Proud disclosure: I serve as a live presenter for the Met in HD series, which begins its new season on Saturday with Verdi’s Macbeth.)

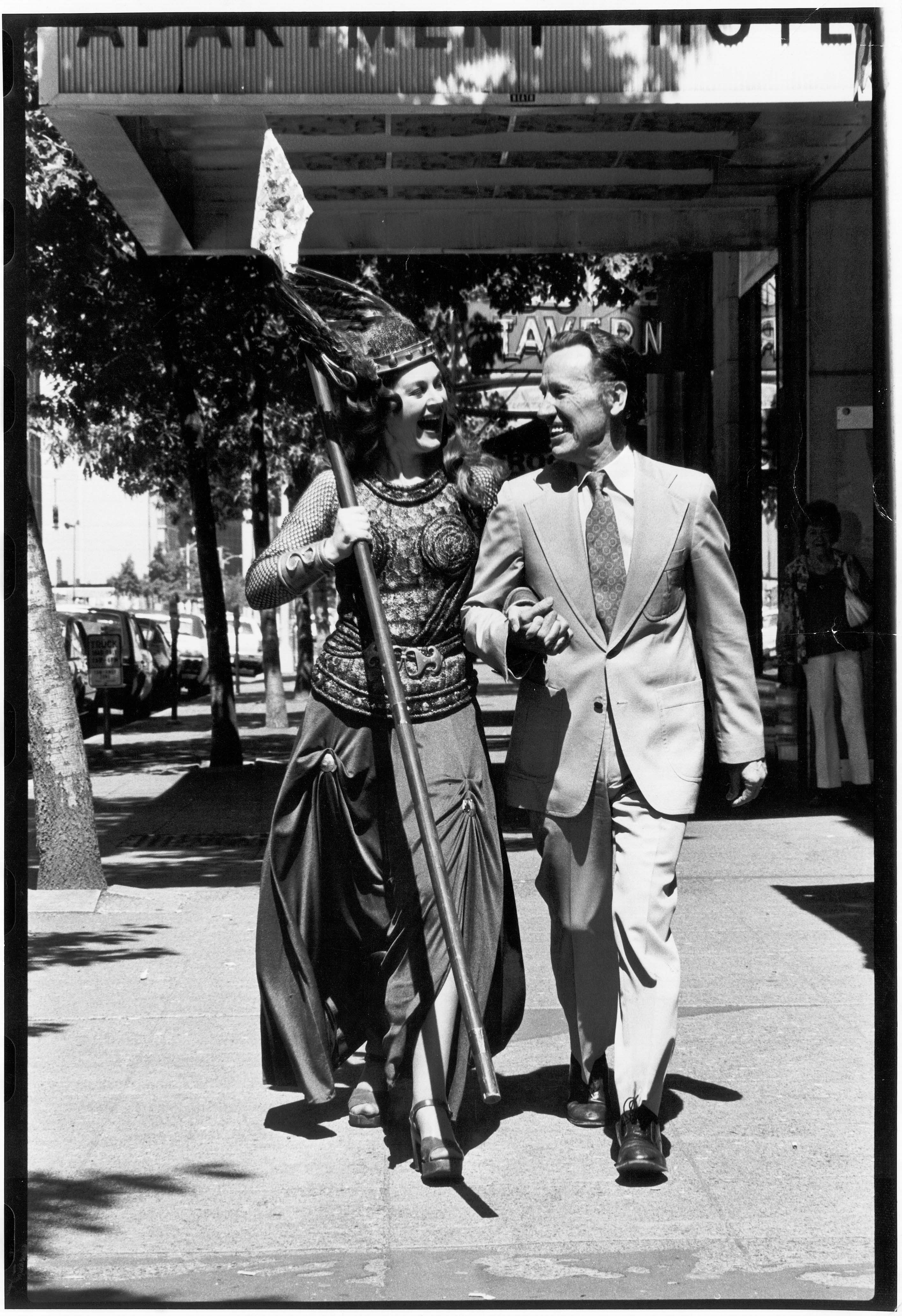

Anna Netrebko as Lady Macbeth and Željko Lučić in the title role of Verdi’s Macbeth. Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera

The reason that arts streaming TV has lagged in the U.S. is almost purely economic. The Met is so huge—its annual budget tops $350 million—that it can afford to take on such a pricey enterprise, and even make money on it. But North American arts organizations lack the generous governmental support offered by most European countries—most critically the free broadcast time on state radio and TV networks.

Even the Los Angeles Philharmonic, one of the nation’s best-endowed institutions, backed off an ambitious plan to stream its concerts. What does reach the small screens are one-off events like L.A. Opera’s recent simulcast of its Roaring ’20s La Traviata.

Aidan Lang is too new to his job as general director of Seattle Opera to opine casually about how his company should approach such a fraught subject as live streaming, but he says, “In my experience at least, neither the people who said it would destroy opera as we know it or the people who said it would revive the medium were right. I haven’t seen any such impact either way.”

Seattle Symphony’s Simon Woods is more decided in the matter. “I see big question marks whether video is ever going to be a useful way to deliver our content,” he says. “The Berlin Philharmonic’s Digital Concert Hall is an amazing technical platform, but it only really exists because it has a substantial amount of corporate sponsorship.

“Now promotion is a different matter. Video is very effective behind the curtain, as it were, and we’re already active in that area. People, especially today’s young people, are fascinated with how things get done, what actually goes on backstage at an institution like the Symphony.

“Where we see real benefit from these technologies in the future is in improved sound and presence in the audio stream. CDs were a revolutionary technology for classical music in their day, but the art has come a long way in 30 years. With contemporary high-bandwidth format, 5.1 surround-sound downloading and streaming could provide a totally new experience to people who have speaker systems equal to the task. If I were to go out on a limb, I think that could be one of the next waves to transform the field.”

While we’re waiting for that next wave, and saving up for a new sound system for our computers and video monitors, there’s already more rich material available in streamed formats than the most ravenous classical fan could consume 24/7. If you haven’t already, dip your toes in; you may find yourself swept away. The Met: Live in HD Pacific Place, 600 Pine St., and other theaters, fathomevents.com. $24. 9:55 a.m. Sat., Oct. 11.

classical@seattleweekly.com