The Great Beauty

Opens Fri., Nov. 29 at Varsity. Not rated. 142 minutes.

Instantly my favorite film thus far this year, Paolo Sorrentino’s account of an aging playboy journalist in Rome casts its eye back to La Dolce Vita (also about a playboy journalist in Rome). As in Fellini’s film, the ossified traditions of the Catholic church also figure in La Grande Bellezza. Yet this movie looks even further back, from the capsized Costa Concordia to the ruins and reproachful marble statues of antiquity.

“I feel old,” says Jep (the sublime Toni Servillo) soon after the debauch of his 65th birthday party. He’s been coasting on the success of his first and only novel, 40 years prior, content with his goal to be king of Rome’s high life. Which he is, with a posh apartment and terrace overlooking the Colosseum, a faithful maid and aristocratic friends, and low-hanging magazine assignments that keep him above the waterline. Again, think of the Costa Concordia, which Jep surveys with silent, morose recognition. The vessel isn’t merely a metaphor for Italy’s stasis and decline, it’s his emblem, too, in the fantastic fourth film by Sorrentino (Il Divo, This Must Be the Place).

Who cares for Rome’s past glories? In Sorrentino’s amazing first sequence, set to choral moans, only a gaggle of Japanese tourists. With its elegantly wandering camerawork, shot in widescreen by Luca Bigazzi, The Great Beauty then careens into the dissolute now—one of the movie’s two extended party scenes, in which the Jep-setters lose themselves in gaudy, dancing abandon. They want nothing to do with history; that’s just for the sightseers.

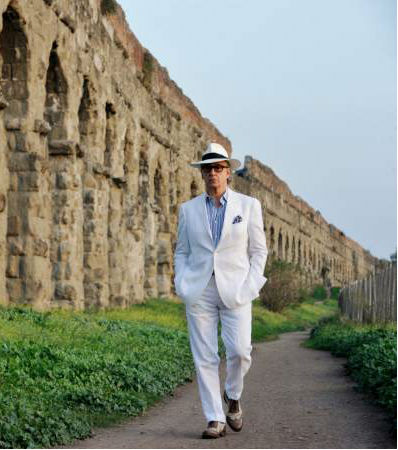

Yet Jep hasn’t lost his eye for social absurdities and human behavior. He’s a dandy with thinning hair brushed back and a girdle beneath his silk shirt. False appearances are all that count, but it takes intelligence to deceive. In one adroit sequence, he explains to a new stripper girlfriend—while helping her choose a tasteful funeral dress—exactly what to say and where to stand at the service. Then he delivers the perfect performance of mourning for a tortured young guy who hardly mattered to him.

It takes another death, that of his long-lost provincial girlfriend, to jolt Jep out of his gilded complacency. Disgust—and then perhaps self-disgust—begins to color his perception of a Botox party, the food obsessions of a prominent cardinal, the splatter-art demonstration of a child artist who actually wants to be a veterinarian, and the whole “debauched country.” What’s the Italian term for flaneur? That’s where Jep starts out, calling himself a misanthrope and failed Proustian. Yet his gaze grows ever more cutting, as when he performs a brutal takedown of a fellow writer in whom he sees “a life in tatters, like the rest of us. We’re all on the brink of despair.” Gradually his petty cynicism becomes more profound, even lyrical. We glimpse his youth and lost love, and Jep even sees the sea on his ceiling—a tantalizing vision of escape, possibly salvation.

The brilliant Servillo makes Jep both suave and somber, a guy living parallel lives in hectic ballrooms and in his head. His wry glances are both mocking and wincing, appropriate for a movie that’s simultaneously bursting with life and regret.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com