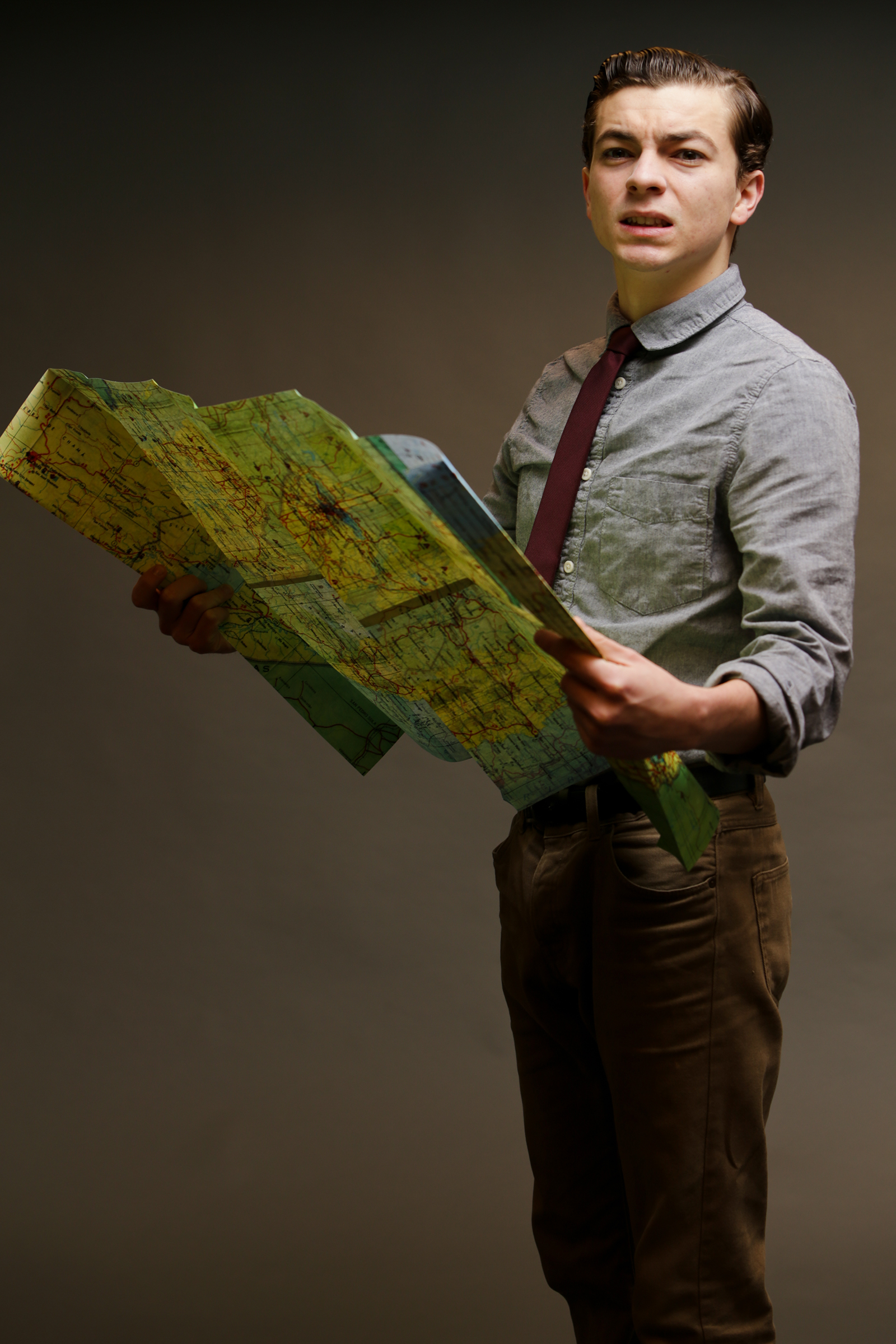

The Chinese term guanxi, at a basic level, can refer to networking, connections, or relationships. More deeply, to a native speaker, it denotes the mutual responsibility owed between two people or groups. In the fast-growing China of David Henry Hwang’s 2011 comedy, it’s imperative to understand guanxi. And as protagonist Daniel (Evan Whitfield) warns, always bring a translator.

Dejected Daniel has fled recession-afflicted Cleveland to try his luck in in China, where he gets tangled in a web of guanxi and misunderstanding. Trying to sell bilingual signage, he’s pegged as being honest and innocent by Xi Yan (Kathy Hsieh), vice minister of a small—only four million!—inland city. She isn’t so innocent; and her gall, desire, and ambition will gradually be revealed. Daniel hires English tutor-cum-consultant Peter (Guy Nelson) to broker a deal between his firm and the Minister of Guiyang (Hing Lam). Daniel argues that his signs can help avoid embarrassing mistranslations—for instance, “deformed man toilet” for “handicap-accessible restroom” or “slip and fall carefully” for “be careful not to slip and fall.”

But enter guanxi. Peter and the minister have a secret past: Peter tutored the latter’s son and got him into the University of Bath. Peter is owed a favor, though the minister has no desire to award Daniel a contract. Meanwhile, harboring her own ulterior motives, Xi keeps Daniel in town by instigating an affair that will upset Guiyang’s current regime.

Chinglish is quick-paced, quick-witted, and brimming with humor. Nearly one-quarter of the play is spoken in Mandarin (with projected subtitles that we trust are being translated appropriately). What makes us chuckle, though, are the mistranslations and communication breakdowns among Hwang’s characters. It’s like that game of telephone, where children whisper a single phrase around the room until it’s mangled and unrecognizable.

Also being mediated from one idiom to another is some underlying pathos. Director Annie Lareau helps us to see genuine feeling between Daniel and Xi. Particularly poignant is the latter’s description of love and marriage—which to her can be mutually exclusive. Carey Wong’s minimalist set design lends further focus to such emotionally naked moments among the laughs.

Hwang, who earned a Tony for his 1988 M. Butterfly, isn’t out to write a serious meditation on U.S./Chinese economic relations. Nor is Chinglish a full-on farce. Rather, he relishes—as we do—scrambling words in a sentence just as much as misplacing an unassuming Ohioan into a foreign culture.

stage@seattleweekly.com

CHINGLISH ArtsWest, 4711 California Ave. S.W., 938-0339, artswest.org. $15–$34.50. 7:30 p.m. Wed.–Sat., 3 p.m. Sun. Ends March 29.