FOR A GENIUS, Edward Albee is one dumb bastard. His gift is for dialogue: His characters clash like rams without a thought in their heads, just brute instinct and perfect aim. Interviews prove that ideas are not his forte, and when he wrote his most famous play (originally to be called Exorcism: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?), the first draft left out the main ideathe imaginary baby, the unspeakable truth that is the point of all that exhausting exorcising by the quarrelsome couple. He put the baby in later to give the drama a point, a resolution. But the subject of their argument is really beside the point: The play is argument without ideas. It’s not “about” anything but character and beautifully skillful conflict, like an Ali-Frazier fight.

The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? (runs through Sunday, Aug. 17, at ACT Theatre, 206-292-7676) is a lot like Woolf. Mostly, it’s a 100-minute argument between a man and wife reluctantly exorcising their dirtiest marital secretnot a fake baby but the man’s romance with a ruminant. Martin (Brian Kerwin) is a more eminent husband than his predecessor, George. At 50, he’s won life’s lotto: the Pritzker Prize for architecture, an Architectural Digest home, marriage to a picture-perfect frau, Stevie (Cynthia Mace), as sleek as Martha was slatternly. Their teenage son Billy (Ian Fraser) is quite real; he’s gay, Martin disapproves, but their dispute is cute, not disturbing.

What’s disturbing is the odd smell Stevie sniffs on Martin’s clothing and his confession to zoophilia when his school chum Ross (Frank Corrado) comes to film a TV interview about Martin’s brilliant career. The play’s first scenes are arch, dry Noel Coward pastiche; after Stevie finds out about the goat, the drawing-room farce starts to sprout scarlet fangs. Her sarcasm is both funny and scary. She keeps demanding the sordid details: “How could you tell she was female? A bag o’ nipples dragging in the dung?” He refuses to get specific, insisting he’s found true love. The dialogue is magically fluid, lifelike and artificial, syncopated in a way that makes me realize Mamet minored in Albee when he was majoring in Pinter.

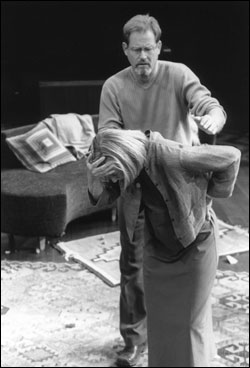

You couldn’t ask for a more virtuosic performance of these masterful passages. In director Warner Shook’s production, Kerwin gives Martin a vague, uxorious passivity cloaking a sinister recalcitrance, a little like Richard Burton’s George, more like the pedophile dad in Discovering the Friedmans. Mace, a whirlwind presence, makes Stevie embody Roy Blount’s definition of women: “They live on this gossamer plane filled with blood, and when they think you’ve torn it, they have these steel teeth.” Fraser’s shiny Billy is sitcom-snappy (at first), and Corrado marvelously evokes the broadcaster’s crass, blowhard bluster.

The repartee reveals real pain under pressure as the gags gradually get harsher. The haunted comedy is nonpareil; the play’s first half is a must-see masterpiece. But then out comes Albee’s dirty little secret: He’s a dumb guy who thinks his immense dramatic gift qualifies him as a deep thinker. He abandons comedy to compete with the Greeks and justify the play’s uppity subtitle, Notes Toward a Definition of Tragedy. The interesting strain between funny and scary snaps, and living emotion succumbs to inert, pretentious idea. The goat becomes a clunky symbol for animal passion and misdirected anger. Stevie becomes the self-conscious tragedian, emitting triple howls like Lear. Only Mace’s brilliance hides the arbitrary, unrooted nature of the howls.

And what’s the big idea? Sex happens. Lust is uncontrollable, “normal” life is a fraud, and we should quit being intolerant or unaware. “Is there anything anyone doesn’t get off on, whether we admit it or not?” Martin demands. He mentions a “friend” who got an erection while dandling his infant. “Was it me, Daddy?” asks Martin’s son Billy in a quavery, terrified child’s voice. The scene’s very emotional resonance and complexity refute Martin’s easy, airy defense of polymorphous perversity. Sex happensand then consequences occur in a web of relationships and within the individual heart. Martin can’t describe his goat love, because it’s a meaningless abstraction. I think Martin avoids the subject because Albee simply doesn’t know how to develop the concept. He thinks in comic arguments, not logic; he can put anything into words except an idea.

There is a certain classical power in the play’s final scene, but it’s fakeit fails to connect character with fate, as tragedy demands. Albee once enraged Walter Kerr by saying that Abie’s Irish Rose is a better play than King Lear. Albee is only great when he’s subversively mixing the former with a bit of the latterspicing comedy with a dash of the tragic. When he tries to write Lear straightto grapple with pity and terror and eternal questionshe’s just a big nothing.