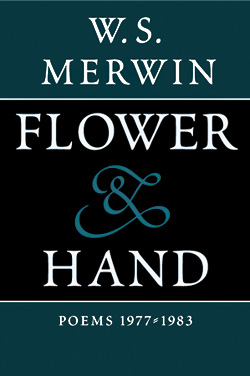

You want to get me excited about book design? Just say “typography.” Wessel and Lieberman must have heard. Last Tuesday, the tony Pioneer Square bookseller put up an exhibit showcasing the work of John D. Berry, who was the house designer for Copper Canyon Press in the early ’90s and who just published a book that’s all about fonts!

Berry, a Seattleite, has written a weekly column in recent years for Creativepro.com—a site for Web designers, graphic artists, and the like—on subjects such as how to use italics, the neutrality of sans serif, and the release of a new Palatino Nova type (be still my heart). Berry was also the editor and publisher of the now-defunct design journal U&lc (Upper and lowercase). Now, New York publisher Mark Batty is releasing a collection of Berry’s essays as part of a new series titled Dot-font—relatively inexpensive, “accessible” books about design in the world.

The crowd included Wessel and Lieberman regulars (i.e., those who can afford collectible or out-of-print books), as well as younger folk, many employed in architecture and design firms.

Berry spoke passionately about the use of fonts in public areas. He was particularly impressed by the downtown library’s liberal use of oversize san serifs that wrap around the desks and cover the floors and said he’d been photographing the library’s interior for an upcoming article. He wants to critique lettering in a public forum. “[Typography] is art in a public space. It should be reviewed like architecture,” he said.

Silly? Maybe. But the in-depth discussion that followed, on the ways in which lettering in public places can actually influence behavior, wasn’t. Consider the lettering revealing the title beside works of art in galleries—didn’t it force me to approach the piece before backing away to view it whole? And how many times had I deemed a restaurant too expensive because of the lettering on its sign? How much was my opinion of a photo skewed by the caption?

“It’s forcing you to see the artwork in a few ways,” said Berry.

Based on lettering alone, I was making the same kind of assumptions in public forums that I did in print.

After looking up from the samples of Berry’s work and walking to the front room of Wessel and Lieberman, I noticed that during my time in the back, the bookstore I’d walked into seemed to have morphed into an art gallery. During my walk home, I looked up and studied the words on the signs, buildings, bus stops, and light posts along the way. I was in a photograph, surrounded by captions.