Stories We Tell

Opens Fri., June 7 at Seven Gables. Rated PG-13. 108 minutes.

The phrase “spoiler alert” gains new currency in the realm of narrative documentary. The reveals and gotchas contained within them are probably already public record—but still, one hesitates to blow the incredible surprises of, say, Searching for Sugar Man for unsuspecting viewers. In the case of Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell, we should be able to dance around the spoilers. And yet, because the actress/director wants not merely to tell a tale of her family’s life, but also to question the reliability of storytelling itself, we might wonder why old-fashioned issues such as suspense and surprise should be part of the program in the first place.

But Stories We Tell is suspenseful and surprising, even if the filmmaker might want to disown those qualities. Polley was a child star in her native Canada, won raves for her youthful roles in The Sweet Hereafter and Go, and snagged an Oscar nomination for writing Away From Her (2006), a much-liked film she also directed.

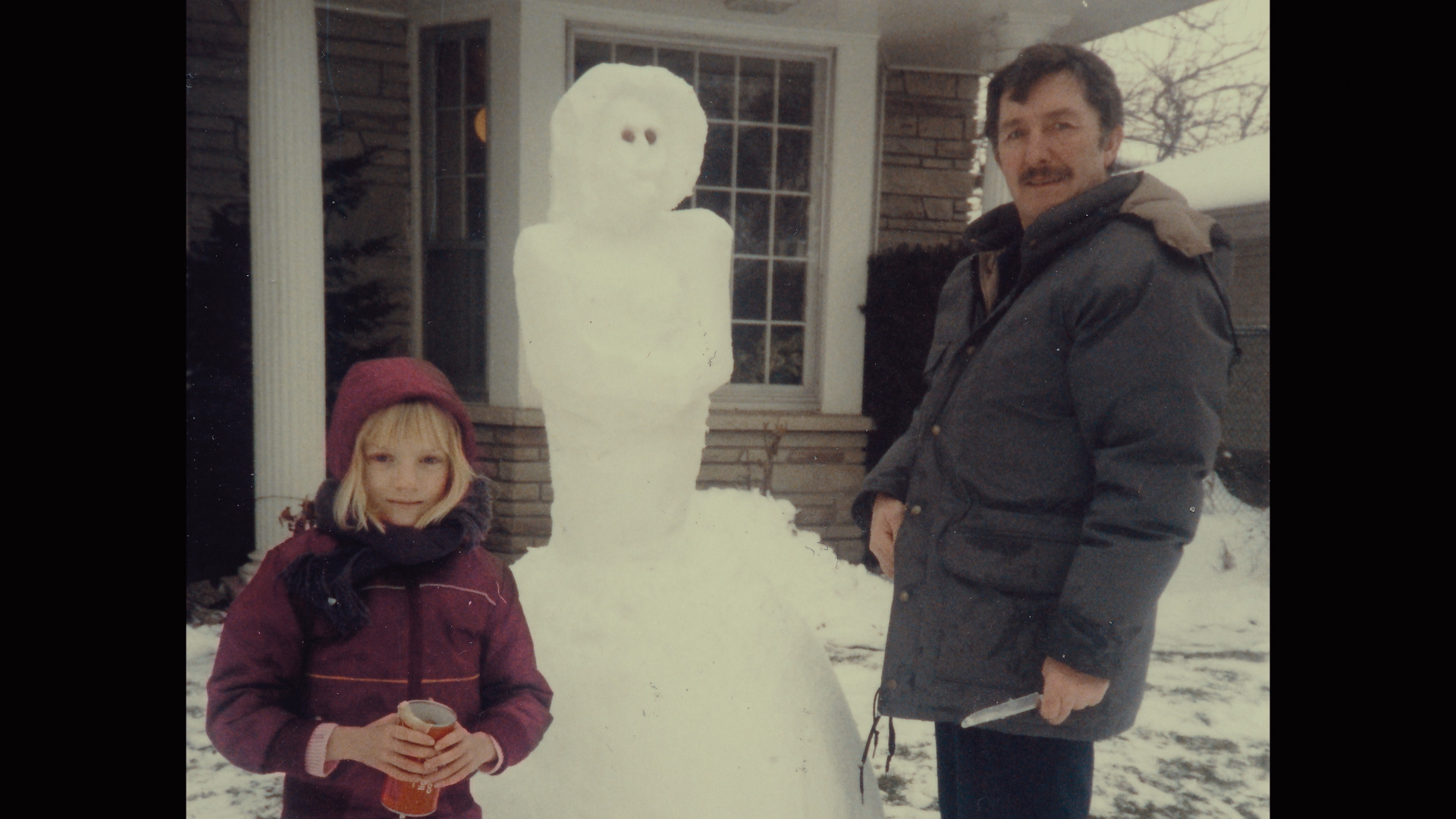

Stories We Tell begins as a portrait of Polley’s mother, Diane. A free-spirited actress who contrasted with Polley’s introspective father Michael (also an actor), Diane mostly sacrificed her career ambitions and had five children. She died when Sarah, the youngest, was 11 years old. We meet the filmmaker’s four siblings, father Michael (who wrote his own narration for the film), and a few of Diane’s friends. The movie begins to focus on Diane’s work in a play in Montreal, away from her Toronto family in a rare idyll, and the fact that Sarah was born nine months after this break.

Introducing the issue of parentage gives the movie a fascinating real-life subject. As though embarrassed by this fascination, Polley keeps shifting the focus to how we can find answers about a subject when everybody involved has his own perspective on the truth (even if her interviewees don’t actually contradict each other all that much). And she reminds us of the artifice of her movie: Even during her father’s sincere and painful voiceover, she is sitting at a sound board, occasionally prodding him to repeat a line for a clearer take.

This scrupulous approach is welcome in an era of sometimes navel-gazing “personal” documentaries. Indeed, the main element missing from Stories We Tell is an anguished confessional or teary breakdown from Sarah Polley. She prefers the role of questioner—interrogating both her subjects and the film form itself—which seems like an elaborate way of getting at (or avoiding?) the situation’s emotional core.

In that spirit, the late-arriving surprises involve not just new information about Diane’s history, but revelations about the movie we’ve been watching. As the storyteller in charge, Polley could’ve laid ou tthat stuff at the beginning; instead, she’s trained us to distrust the stories we tell, including, apparently, this one.

film@seattleweekly.com