By staging version 3.0 of Jake Heggie’s new opera The End of the Affair, forgoing the glamour of a world premiere to give the composer a further chance to polish his work, Seattle Opera is doing the art form a noble service and is being repaid by an absorbing and well-received piece. If Affair (at McCaw Hall through Oct. 29; 206-389-7676, www.seattleopera.org) still has its problematic aspects, they’re largely ones inherited from the Graham Greene novel Heggie and librettist Heather McDonald took as their source.

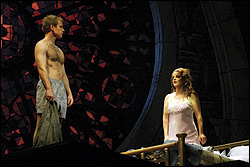

We’re in London during the blitz in the opera’s pivotal scene. The adulterous five-year affair between Sarah Miles and Maurice Bendrix comes to a quick postcoital close during a bombing raid. Sarah, thinking Maurice dead, vows to give him up if God lets him survive. Which God does. But this love/renunciation scene doesn’t open the opera or the novel—the opera’s first hour or so, leading up to this climax in flashback, is set during that awkward period after Sarah leaves Maurice but before he finds out why. There’s a lot of reminiscing here, at the expense of here-and-now action, and a lot of self-effacement by characters (including Sarah’s husband, Henry) too starched to admit to each other how they feel. Thus the audience only slowly gains a sense of who these people are and why we should care. But when we do reach the love scene itself, the combination of soaring ’40s-film-score music, air-raid sirens, a gigantic rose window as a backdrop, and Maurice’s bare bum make it a can’t-miss theatrical moment, recalling composer and critic Virgil Thomson’s dictum “The ideal opera contains one of everything.”

This paper’s readers surely are sophisticated enough re contemporary music that I needn’t reassure you that there’s nothing scary about Heggie’s score. No one who can tolerate the harmonic harshness of, say, a Ravel piano concerto will have any trouble with Affair. Yet Heggie isn’t one of those composers who make such a fetish of “accessibility” that you get the impression, hearing their work, that they would consider it unmannerly to actually capture your attention.

When operas (of any period) fall flat, it’s often because the composer has failed to write a score that drives the action—or failed to understand in the first place that that was his job. Heggie’s orchestral writing has a deeply satisfying vividness and strength, painting and punctuating the drama with striking musical gestures (music you can actually remember 10 seconds later) and conjuring imaginative splashes of color from limited means. Affair requires just a small orchestra, with only single winds and brass, making percussion, harp, and keyboards all the more prominent in the mix. Heggie likes to use them to sprinkle dissonances over a more placid harmonic cushion—a magical, Rosenkavalier-ish effect.

The vocal lines, though, floating wistfully along, don’t move with the same sense of urgency and direction (the ensembles come off better than the solo arias in this regard). Heggie takes great care, perhaps too much care, to follow the natural rhythms of the libretto’s prose. I’m not convinced that “following” the text’s rhythms is an opera composer’s duty. The composer needs to write music that shapes the words, giving them dramatic point by having a clear-cut structure of its own. The vocal writing here starts to sound a bit spineless after a while. Affair also shows a few miscalculations of scenic pacing—the moments with Sarah’s flirtatious mother come to mind—when the action might have moved more quickly, both for its own impact and for the welcome contrast such scenes would have made with the overall mood of reflective bittersweetness.

Details, details. None of this seriously gets in the way, and Heggie has a solid success on his hands. Leonard Foglia’s direction skillfully handles a narrative line constantly folding back on itself, while Michael McGarty’s imposing sets, with gray stone sections of bombed-out cathedral always looming over the action, serve but never suffocate the drama. The committed cast, with Philip Cutlip and James Bobick as the double-cast Maurices and Mary Mills and Edlyn de Oliveira as the Sarahs, leads a production team working hard to change the minds of conservative fans skeptical about the viability and appeal of contemporary opera.