Departing Intiman Artistic Director Bart Sher’s controversial decision to bring a New York–grown production of Othello to Seattle was vindicated with standing ovations for the soul-wrenching import. With a light hand and a painter’s eye, N.Y.–based director Arin Arbus presents an intimate, Shaker-simple universe in which words, deeds, and character can not only shine but combust.

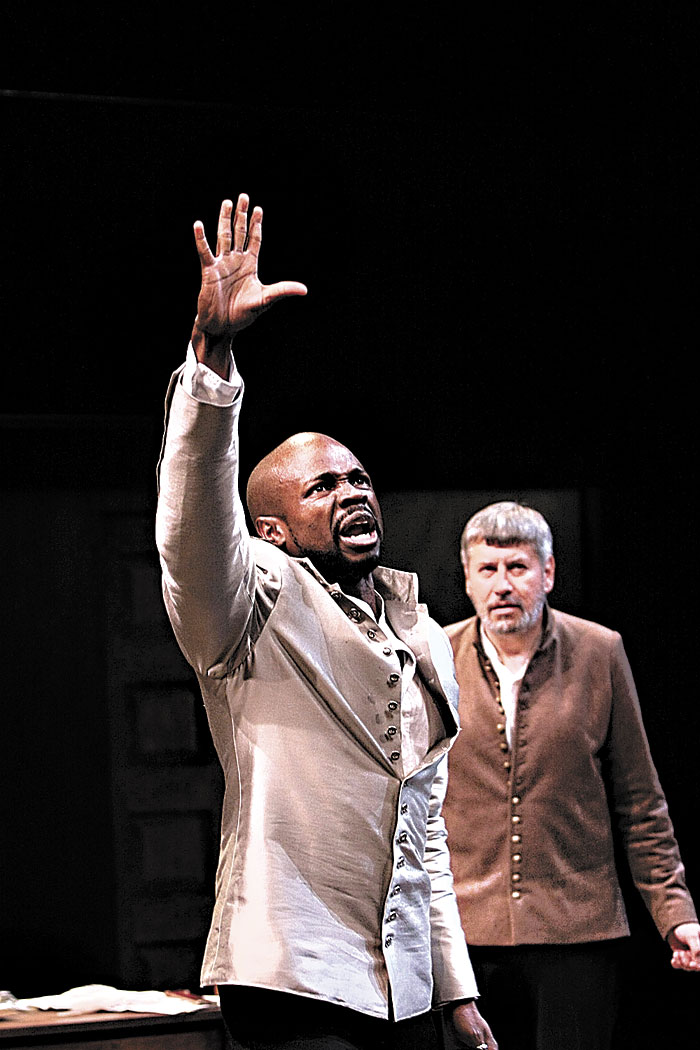

All three of the principal actors joined the production after its New York run this past spring. In an unconventional but effective opening move, Arbus cast middle-aged Brit John Campion as Iago, General Othello’s nefarious liege and confidant. The pathos of age serving youth lends interesting texture to his relationship with virile Othello: a bit like Obama and Biden. Campion plays a nebbishy Iago, one pitiably paunchy and hunchbacked, with sloping features, tiny eyes, and gray whiskers. He speaks in a lowbrow, unidentifiable accent, droning monotonally as though causing his very voice to vanish into the wallpaper, even when boasting to Roderigo “I am not what I am.” The portent is enhanced by the fact that such a studiously dull boob could scarcely exist anywhere near the center of a Shakespearean tale without a deeply perverted motive. Campion’s guy-next-door banality is a chilling reminder that many a neighborhood barstool could be occupied by just such evildoers. The production’s tag is the paranoid “Tell no one.”

Screen heartthrob Sean Patrick Thomas (Save the Last Dance, Barbershop 1 & 2) inhabits the title role with quiet (and über-stylish) confidence, fully believable as the deft Moorish battlefield strategist whose self-doubts in the social sphere cause him to believe the wrong domestic adviser. His martial ability manifests in a commanding physical form and he speaks beautifully and powerfully, his Othello secure in the knowledge of his indispensability to the Venetian empire. As if to eliminate religious difference as a factor in the play’s dramatic friction (Othello is sometimes played as a North African Berber Muslim), Arbus has him wear a cross on the front of his shirt. On such a lean set, Thomas spends significant amounts of time delivering lines rather than doing, yet he’s so present in his—well, hunky—body we don’t mind. Though when we meet him, his faculties are slightly compromised by the vapors of newlywed love. The sight of Desdemona mellows him to a giddy state of emotional vulnerability easily preyed upon by Iago.

Elisabeth Waterston’s Desdemona looks and acts as pure as white light. Clad in a frill-less long white gown, her endless limbs lose their rectitude only to bend achingly toward the Moor. Her body is as stylized as a Mannerist Madonna or a John Currin sylph, yet there’s profundity and wisdom in her innocent eyes, and one of the play’s hardest facts to swallow is that Othello could possibly see duplicity in them. Waterston’s devotion is so blinding that it seems to grow, deepen, and mature even in the face of abuse. It is almost unbearable, in a good way.

In contrast to the striking physical uniqueness of the principal casting, Peter Ksander’s set centers around a simple, rather generic rectangle of well-worn, blackwashed paving boards, with two wooden doors at the rear. A smaller rectangle of light suggests the moonbeams that might filter down into a typical Venetian courtyard. A rainstorm is economically conjured with loud claps of thunder and vertical strings of beads along the back wall. This is not the hyper-austerity of Peter Brook’s Hamlet, but Arbus’ background in visual arts fosters judicious minimalism. The men’s jackets don’t even sport lapels. Without clear indications of time and place, this Venice and Cyprus could be anywhere, anytime. The spare domestic compositions resemble Vermeer’s eerily modern-looking paintings in both arrangement and lighting. In most scenes the spirit of a room is evoked with one or two pieces of furniture. Arbus’ palette seems to come from the ethnographic imagination: black, white, brown, orange, and gray. The people are the world.

The cumulative effect of such relentless human focus pays off in the final character-sprint toward catastrophe, so deep is the emotional investment at that point. Those implausible elements of the murder and aftermath which caused Lawrence Olivier to call the title role “unplayable” seem inconsequential. Even after the most cared-about characters are gone, the raw human investment transfers to the second tier of sympathetic figures, principally Desdemona’s handmaiden Emilia and Othello’s lieutenant Cassio. Like an arsonist at the scene of a blaze, Iago looks on the carnage with poorly disguised delight. Like the best playwrights—with Arbus’ ascetic kindling—Iago’s meticulous plot design has set a world on fire.