AT THE AGE OF 25, Rebecca Walker learns the details of her birth certificate. Her father reveals that “next to boxes labeled ‘Mother’s Race’ and ‘Father’s Race,’ which read Negro and Caucasian, there is a curious note tucked into the margin. ‘Correct?’ it says.” Documenting Walker’s life through high school graduation, Black, White, and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self tracks her constantly morphing identity—street-savvy girl, Jewish-American princess, Puertorrique�And, in turn, she comments on questions thrust at her by a racist society: Are mixed-race children “correct” or “incorrect”?

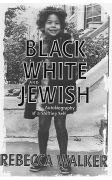

Black, White, and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self

by Rebecca Walker (Riverhead Books, $23.95)

“I am not tragic,” Walker understands as a child in Mississippi. The daughter of celebrated author Alice Walker and progressive Jewish lawyer Mel Leventhal—both participants in the Civil Rights struggle in the South—she asserts that “I am not a bastard, the product of rape, the child of some white devil. I am a Movement Child. My parents tell me I can do anything I put my mind to, that I can be anything I want.” When her parents divorce, Walker’s confidence wavers. While her mother focuses on feminism and Black Power and her father marries a Jewish woman and moves to the suburbs, Walker finds herself shuttled from Brooklyn to Washington, DC, to San Francisco to the Bronx as part of her parents’ strange plan for their daughter to switch guardians every two years. Walker writes, “For [my parents] there is a return to what is familiar, safe, expected. For me there is a turning away from all of those things.” Alternating between family, neighborhoods, and friends, Walker constantly struggles to adapt: “I tend toward that which destabilizes and feels most like home: change, impermanence, a cursed quality pattern of in and out, here and there, city to city, place to place.”

LIGHTHEARTED AND APOLITICAL, the majority of Walker’s memoir recalls often superfluous details from the author’s early years: her first boyfriend, her Sergio Valente jeans, her Chaka Khan 45, her gal pals. Despite the title of the book, her Jewishness is something vague and related to her father: She changes her last name from Leventhal to Walker “because I do not feel an affinity with whiteness, with what Jewishness has become.”

Walker’s narrative is strongest when she communicates exactly how it feels to be a minority in “the race-obsessed United States.” Seen by others as somewhere between black and white, she feels the sting of all insults lobbed from one group at the other. Barbed memories line the pages of Black, White, and Jewish, as Walker experiences white-on-black racism (her elementary school crush tells her he doesn’t like black girls; her adolescent boyfriend’s hockey buddies “razzed him for going out with a nigger,”) as well as black-on-white racism (a former friend calls her a “yellow bitch”; her uncle labels her “white” mannerisms “the crackers”).

Most refreshing about the 30-year-old Walker’s memoir is that, in the end—if there is an end of an autobiography in which the author’s not yet in college—she embraces, and thus transcends, the ambiguity of her childhood. At one point, she remembers an acquaintance complaining that her mixed-race daughter will always be known as black in the “real world.” Black, White, and Jewish is Walker’s personal account of that real world—a place that nourishes anger and cynicism—and her eventual discovery that the only real world is the one we create. Even with that note on her birth certificate asking “Correct?” Walker can thrive in the margin, not because she’s in between black and white but because she moves beyond these categories. “I feel as if we speak two different languages,” she writes, “and I am the only one who can speak both, who even knows that there is more than one to be learned.”

Rebecca Walker reads at Elliott Bay Book Co. on Thursday, January 18 at 7:30.