Dr. Tom Furness III was stationed at Dayton, Ohio’s Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in the early ’70s when he started practicing transcendental meditation. Inspired to take it up by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, famed guru to the Beatles and the Beach Boys, the brilliant young electrical engineer with a North Carolinian drawl noticed right away the dramatic effects it was having on his perception.

“After I’d finish meditating, all the colors were brighter. You could see every drop of water,” Furness, still a practitioner at 73, tells me in his private laboratory on the outskirts of the U District in Seattle as he sips tea. “I found I was able to pay attention to more. It sort of enlarged your capacity to take things in.”

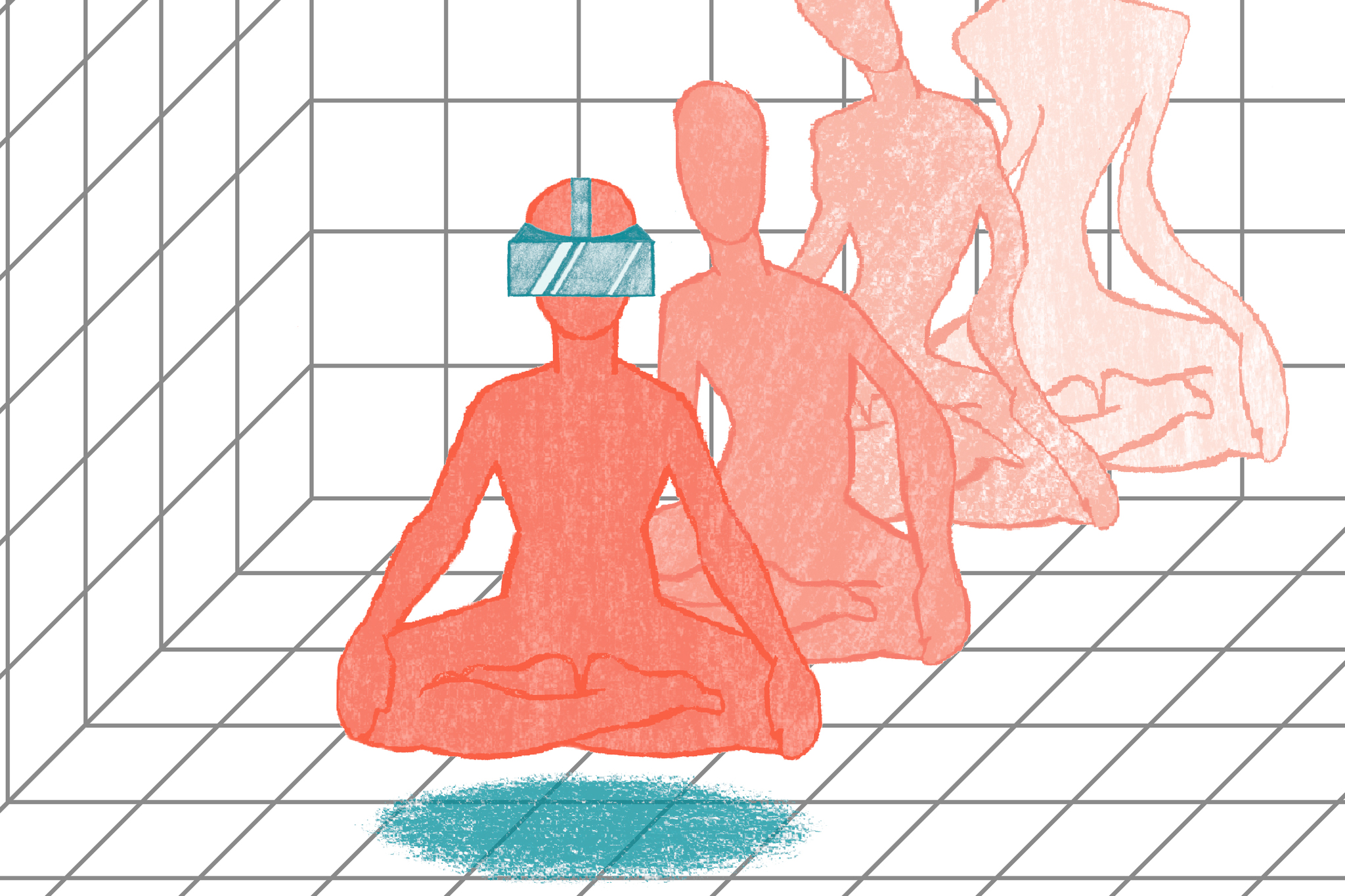

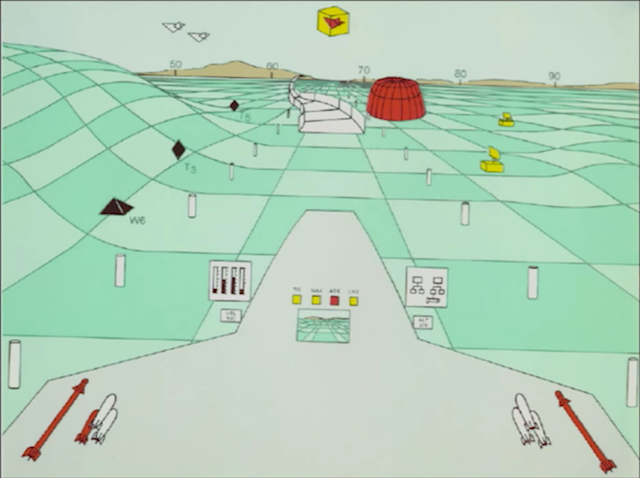

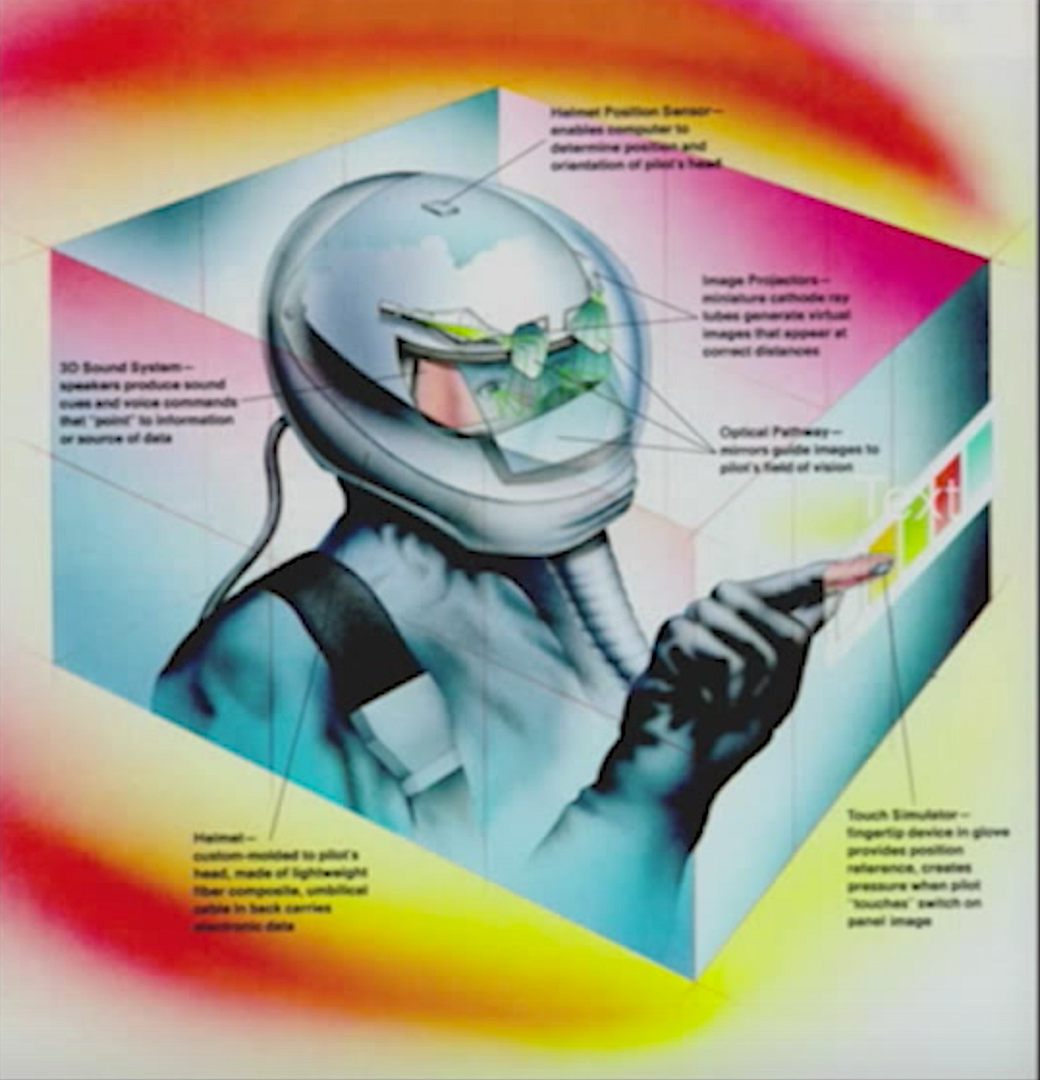

Coincidentally, Furness was stationed at Wright-Patterson from 1966 to 1989, leading a groundbreaking project to enlarge the capacity of fighter pilots to take things in: what is now known as The Super Cockpit program. By putting on what Furness calls a “magic helmet, magic flight suit, and magic gloves,” a pilot was transported into a new world with a head-tracking, immersive 120-degree view, where they could see, in real time, avionics and radar data as well as computer-generated 3D maps from the terrain around them. The pilots could control the plane through this virtual environment using gestures, utterances, and head and eye movements. The man/machine symbiosis made piloting the plane far more natural, reducing the need for complex controls.

Concept drawings of the ’80s iteration of the Super Cockpit. Courtesy Tom Furness

Along with Ivan Sutherland’s “Sword of Damocles” and Morton Heilig’s “Sensorama,” Furness had invented one of the first three virtual-reality interfaces. Spiritually, however, his historic scientific achievement was bothering him.

“Wars are ridiculous,” he says. “All my time as a warrior, what a waste. We’re at childhood’s end now in civilization; we’ve got to grow up and take responsibility for what’s been done—our culpability in what’s happening to our planet and the people on it. It’s just not working. We’re destroying it. I believe that VR is the tool of our age that will help propel us into transcendence. Where we connect again, and learn to fully awaken our senses again. Is it transcendence from our bodies? No. What it is, is helping us realize what we already have, and how wonderful it is.”

Seattle is arguably the center of the virtual- and augmented-reality universe right now. The world’s leading consumer VR/AR hardware developers, including HTC, Oculus, Magic Leap, Microsoft, and Google (responsible for the cheapest headset available, the $15 iPhone-enabled Google Cardboard) all either have their main offices or branch offices in town. As the tech has become more affordable, the number of VR/AR software and content producers in Seattle has also boomed. But, as in the rest of the world, the vast majority of the focus, content, and discussion here has been on virtual-reality video-game entertainment, a fledgling industry drowning in cash that has yet to deliver an artful, standard-bearing app—or even figure out how to prevent motion-induced nausea. For now, it largely remains in the gee-whiz stage—despite insistence from gaming giants like Valve and Playstation that VR gaming is well on its way.

But the most fascinating VR and AR work being done in Seattle right now—as always, in the margins—is aiming much higher, and has already seen astounding, potentially world-altering results. These developers and producers may utilize video-game paradigms in their work, but the goal isn’t simply entertainment. They’re out to radically transform psychology, medicine, therapy, education, policy-making, social and environmental justice, storytelling, and, ultimately, the limits of human consciousness and perception. Unlike the VR gaming industry, whose Seattle roots extend back to the early 2010s, this particular branch of virtual reality and its transformational promise stretches all the way back to 1989—the year Furness quit the Super Cockpit project and moved here to open the UW’s Human Interface Technology Laboratory—aka the HITLab.

Furness with his Virtual Vision Sport from 1993, the first commercially available VR, which flopped upon release. GIF by Sofia Lee

Furness created his private RATLab, where he employs a small team of developers, to work on personal VR and classified projects outside of the University. GIF by Sofia Lee

The HITLab is indisputably the world’s foremost pioneering virtual-reality lab, and, in its early days, was one of the few virtual-reality research labs of its kind in the world. Although Furness’ expertise is in electrical engineering, he purposefully made the lab “ecumenical”—it did not belong to any one department. At its peak, the HITlab reached 120 students. Today, federated HITLab branches have opened in New Zealand and Australia.

“It was a chaotic, interesting place,” Ari Hollander, a very early student of Furness’ at UW’s HITLab, tells me. “It was full of artists and psychologists. When I first got there, there were people into sculpture and multimedia and architecture and what have you, every discipline you could imagine. In the early days we were in these weird digs in Fluke Hall—they hadn’t built the walls in parts of it, so it was all open. One guy would go rollerblading around while he was thinking about engineering problems. Just about anything you point to now that people think is new with virtual reality, Tom already did it there.”

Hollander landed at the HITLab as a grad student in 1991 with a far-flung background himself—an astrophysics major from UC Berkeley who broadened his undergrad studies by poking around into media, making videos about dark matter, and falling down a biological psychology and psychoacoustics rabbit hole studying “how our senses lead to our reality.” His junior and senior year, he helped build the house of cards on the cover of The Grateful Dead’s worst album, 1989’s Built to Last, and also did some CGI work for the band. At the HITLab, for his senior thesis project, he noted that the part of the brain used to process sight also processes sound, so he asked the question: “Why can’t we hear shapes?” It turns out, we kind of can—Hollander had some success in creating virtual sounds that test subjects were able to perceive the “shape” of. Soon after, he became the creative/technical director of the HITLab and in 1995 helped start Firsthand Technology, a company he hoped would bring VR out of the lab and into the public for a variety of applications.

Of course, VR equipment at this time was incredibly expensive and limited. The SGI Onyx, used to render the clunky graphics in the HITLab’s assortment of virtual worlds, cost $1 million on its own. Thus Hollander’s attempts to get early virtual-reality equipment in schools for educational purposes crashed into the reality of restrictive school budgets—despite enthusiasm and marked results in the students themselves, who were able to sample the setups during the HITLab’s VR RV school tour, which took the gear on the road showing off immersive, interactive science lessons. It wouldn’t take long until Hollander fell into the VR field that’s preoccupied him to this day and led to his newest company Deepstream VR: cybertherapy and pain relief.

In 1996, a Seattle woman named Joanne Sakelaris saw an episode of Scientific American Frontiers on KCTS. Host Alan Alda had visited VR researchers in Atlanta who were finding success treating people with a fear of heights. By placing the patient in a virtual world at a simulated tall height and conducting repeated exposure therapy, the person’s fear of real-world heights went away.

Sakelaris related to the phobia patient on TV, and thought VR treatment might also help her with her clinical, 20-year arachnophobia. Her fear of spiders was so extreme, she regularly fumigated her car with pesticides and smoke, sealed the cracks in her room with duct tape every night, and eventually became afraid to leave her house. Sakelaris asked her therapist, Al Carlin, if VR research was being done in arachnophobia therapy. Carlin reached out to HITLab researcher Hunter Hoffman, who within a few weeks and with the help of Hollander, rendered a VR kitchen with goofy, polygonal spiders in it.

They called it SpiderWorld.

SpiderWorld worked by gradually ramping up the intensity of Sakelaris’ exposure to the cyberspiders in each session. At first you were simply in the room with the spider. Then it was surprising you in the cupboard, descending from the ceiling, or jumping out at you. Then you were batting it away with your cyberhand into the virtual sink’s garbage disposal. Finally, at the end, you were reaching out and touching a realistic furry toy spider in real life mapped to the location of the virtual spider in the simulation.

Hunter Hoffman (above) walking Sakelaris through SpiderWorld. Courtesy Tom Furness/HITLab

Despite the rough graphics, Sakelaris had a very visceral response to the cyberspiders at first—she would panic and distance herself when they appeared, and her palms would start to sweat. After two one-hour sessions, Sakelaris reported, she was able to verbally confront the “cigar-smoking thug leader” spider in one of her long recurring nightmares for the first time. After three more weeks of therapy, the spiders had completely vanished from her dream, she said—only their cobwebs remained. By the end of the 12-session run, Sakelaris was able to hold real, furry tarantulas without anxiety, as she did on a follow-up episode of Scientific American Frontiers. “I’d never been able to go camping before,” she says, breaking down in tears on camera; “that to me is just … great.”

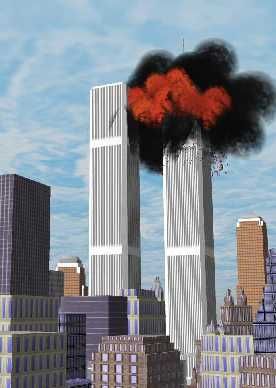

In the early to mid-2000s, Hollander would find similarly startling results using virtual-reality exposure therapy to successfully treat post-traumatic stress disorder in Iraq war veterans and survivors of 9/11 by running simulations of the attacks on the Twin Towers. Just as with the spiders, the intensity of the simulation grew as the sessions progressed. On the lowest setting, the participant simply stood at the base of the Twin Towers. “Just standing there in a virtual world with this at-the-time fairly coarse polygonal representation of the World Trade Center was a lot for them,” Hollander says. On the next setting, a plane would fly by, but wouldn’t hit anything. On the next setting, the plane would hit the first tower; on the next, the second tower. On the final setting, human figures with rag-doll physics applied to them would begin to fall out of the buildings.

One survivor, describing her experience in the simulation, talked about being inside the World Trade Tower on the stairs, the room full of smoke. “The only thing is,” Hollander says, “you couldn’t go inside the towers in the simulation. I would know, I built it.” The patient’s real memories and virtual memories were beginning to blur—a testament to the powerful role “place” has in forming memories in the brain.

One survivor, describing her experience in the simulation, talked about being inside the World Trade Tower on the stairs, the room full of smoke. “The only thing is,” Hollander says, “you couldn’t go inside the towers in the simulation. I would know, I built it.” The patient’s real memories and virtual memories were beginning to blur—a testament to the powerful role “place” has in forming memories in the brain.

A few years after the surprising success of the arachnophobia experiment, Hoffman, Furness, and HITLab colleage Dave Patterson started thinking about the neuroscience underpinning Sakelaris’ dramatic transformation. They found some clues from the work of Dr. V.S. Ramachandran, a psychologist from UC San Diego who had successfully treated phantom-limb pain using a “virtual image.” The test patient’s arm had been amputated after months of painful paralysis in a sling, but instead of fixing the pain, the amputation left the patient with a very painful “paralyzed” phantom limb. Even though the arm was gone, the months of paralysis had mapped the arm pain to the patient’s brain, giving him the sensation it was still present.

By setting up a few simple boxes and mirrors, Ramachandran created an illusion that reflected the patient’s existing arm and made it appear where his old arm used to be. By repeatedly moving this “virtual” arm, even though the patient knew it wasn’t real, the simple visual was able to completely remap his brain. Suddenly the phantom limb was no longer “paralyzed,” and the pain disappeared. “He was redrawing structures in the brain in how we feel our bodies and pain in our bodies in a very concrete way,” Hollander says. “Hunter Hoffman looked at that and said, well, what can we do with that?”

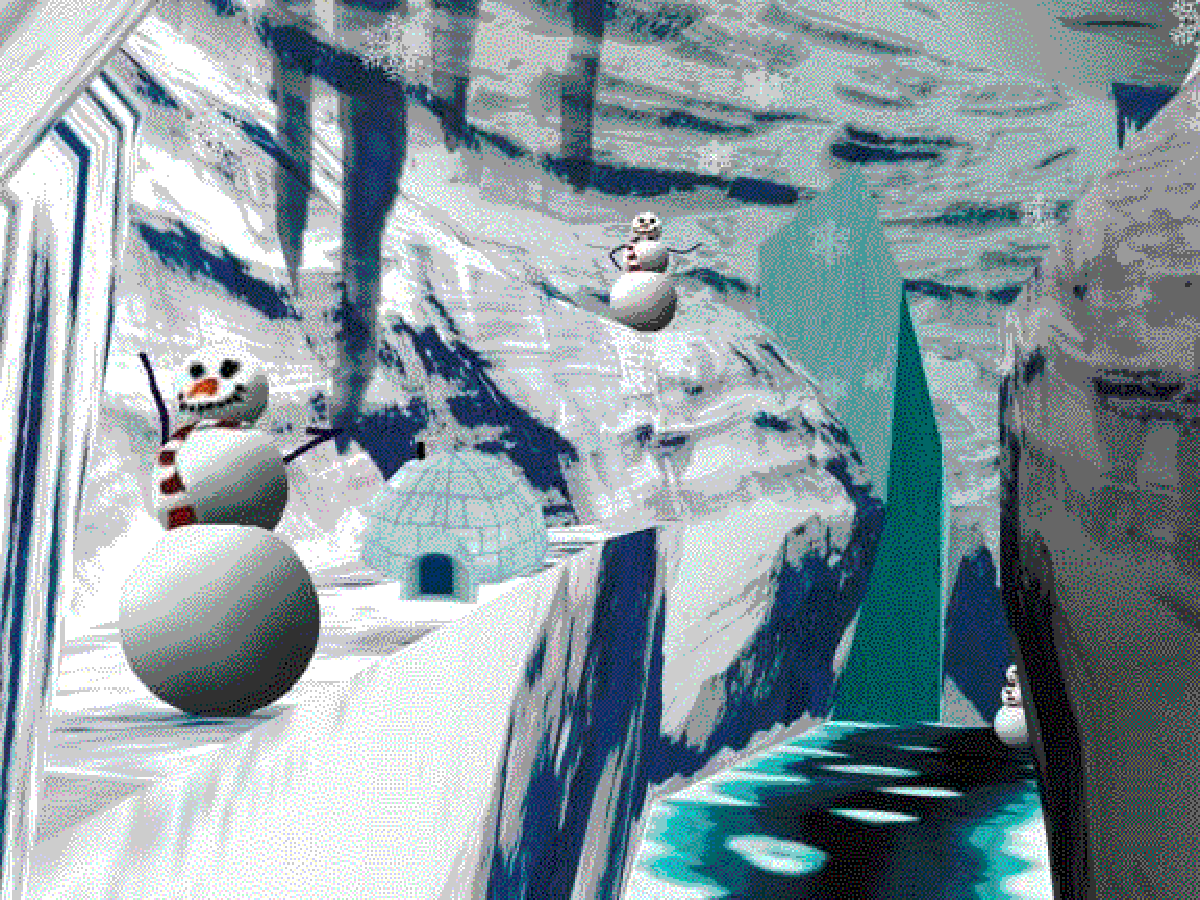

Intrigued by the implications of Ramachandran’s study, Hoffman put Harborview’s severe burn patients in a VR application he created called SnowWorld. In the program, the user slowly floated through a snowy canyon full of penguins, woolly mammoths, and snowmen and shot snowballs at the interactive environment by moving their head.

“I was watching some of this going on, and the patients would be receiving some kind of wound care,” Furness tells me, “either removing staples from a skin graft, or soaking a patient in a big bathtub and sloughing off the dead skin. Any time you did that, even with medication, you couldn’t medicate a patient enough—there was breakthrough pain. You put them in SnowWorld, they’re floating through the canyon, shooting snowballs, and then you ask the person, ‘OK, well, what was your pain index?’ and they’d say, ‘Well, when are you going to start?’ when the nurses had already finished.”

Brain scans later revealed just how effective SnowWorld ’s acute pain-killing power was. “From the research, we found out it was better than morphine for pain relief,” Hollander says, “it was just like, ‘Holy shit … ’ ”

Later, a study in Knoxville, Tenn., piggybacking on the HITLab findings showed immersive VR was even more effective on people with chronic pain. Of 30 patients with chronic neuropathic pain tested—some of whom had survived sarin gas attacks and were living with spinal-cord stimulators—90 percent reported at least 50 to 60 percent pain relief (morphine, for comparison, provides 25 to 30). A third of the patients reported 100 percent pain relief—some for as long as 48 hours after the simulation had ended.

“Something profound was happening there,” Hollander says.

A Harborview burn patient plays SnowWorld during typically painful wound care. Courtesy Tom Furness/HITLab

When Hollander and I meet to chat, he’s just returned from Atlanta, where he went to see Lindsey Ferrentino’s Ugly Lies the Bone for the first time. The New York Times–acclaimed stage production, which debuted last year, is based on the real story of First Lieutenant Samuel Brown, who returned from Afghanistan with full-body third-degree burns, destined for years of painful skin grafts, but found relief and hope through SnowWorld. Hollander, who took over SnowWorld’s development in 2005 through Firsthand Technology, said the show was, unsurprisingly, pretty surreal.

“It’s wild to have written a piece of software and have it inspire a playwright!” he says, laughing. “But really, the profound effect of this is, you know, pain relief and software. Software! It’s scalable, it’s distributable. It’s something you have control over. The way pain relief is practiced in this country is fundamentally broken. We’ve got four percent of the world’s population in the U.S. and we’re using 80 percent of the opioids. Opioids are bad medication.”

In Cool!, Hollander’s sequel to SnowWorld, the player shoots fish to otters. Courtesy Ari Hollander

Through his new company Deepstream VR, Hollander is working on getting VR systems running Cool!, the updated, spiritual successor to SnowWorld (this time with a high-definition river setting and lots of furry otters) in hospitals around the country—but his long-term goal is even more ambitious. Using biofeedback sensors—think Fitbits on steroids—Hollander wants to introduce VR technology to the at-home market that can monitor and detect a patient’s pain in real time and automatically tweak the parameters of the painkiller simulation to optimize treatment without a lab or doctor present.

To demonstrate the power of biofeedback in tandem with VR—a concept he was having trouble verbally communicating to people—Hollander recently made a demo he’s calling Glow!, a VR meditation program. “Mindfulness is one of the most effective ways to treat pain,” Hollander explains. “VR pain relief is all about getting you out of your body—it’s this out-of-body experience. But mindfulness is all about putting you into your body. So there’s this design conundrum—how do you go outward and inward at the same time? Sounds pretty Zen, right? So what we did is, we attached biosensors reading your body to the virtual environment.”

Glow!’s game mechanics make the user relax to succeed. Courtesy Ari Hollander

In Glow!, the user is immersed in a virtual forest full of distant, flitting fireflies. When the player closes their hands, they activate their “force,” which they can use to draw fireflies in. There’s one catch, though—the strength and range of your “force” directly correlates with the readings from the heart-rate monitor you’re wearing. The more relaxed you are, the more fireflies you can draw in. You “win” the game by lowering your heart rate enough to max out your force, draw in all the fireflies, mesh them into a singular glowing mass, and ultimately, feed them to a mythical lantern creature that appears out of a pond.

“It’s the first time I’ve felt like a VR program was reading my mind,” Hollander says of the first time he tried it. “The key to biofeedback is ‘You’re going in the right direction.’ If you do it right, it feels like you’re flexing a muscle you didn’t know you had.”

Essentially, biofeedback VR meditation allows its user a shortcut to mindfulness. If you think that might upset Buddhists, you’d be wrong. “There is no paradox in finding your true self via virtual reality because everyday reality is already a simulation,” spiritual guru Deepak Chopra recently told The Guardian. Chopra’s developing his own VR series, which just kicked off with Finding Your True Self, a 20-minute psychedelic relaxation and meditation experience for the HTC Vive and Samsung Gear VR that features the virtual visage of Buddha and the Bodhi tree under which he attained enlightenment.

This week, thanks to Sandy Cioffi, Seattleites will have the chance to swap their gender, for a moment. At Twist360, billed as “what may be the first-ever immersive media festival exploring the intersection of queer culture, art, cinema, and technology,” Cioffi, who is organizing and curating the event through her Seattle-based VR production group fearless360°, is bringing Barcelona’s The Machine to Be Another experiment to Seattle for the first time.

“Everyone talks about ‘Let’s smash the use of gender binaries,’ ” Cioffi tells me while sitting in her co-working space at Capitol Hill’s Cloud Room. “Great! Great objective. But we’re asking the question, can this help to smash binaries? Or does this reinforce them?”

In the “embodiment” experiment, which can theoretically be used to swap any identities, participants will be asked to choose a line. “We’re saying, if you’re feeling masculine today, get in that line, if you’re feeling feminine, get in that line,” Cioffi tells me. “Tomorrow, you can come back and get in the other line.”

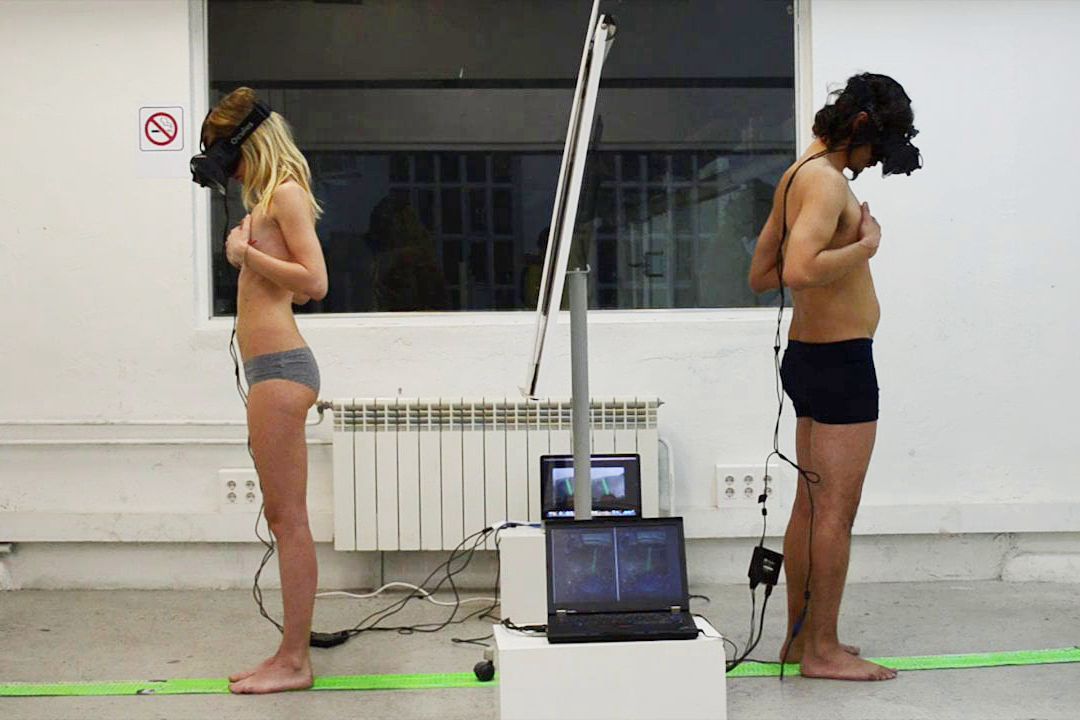

The two participants sit across from one another, put on their headsets, and, through the use of head-mounted cameras, are suddenly plunged into each other’s first-person perspective. By making sure to move slowly and synchronize their movements with each other, the two participants possess each other’s bodies, see through each other’s eyes, and for a brief moment engage in a sort of glacial transportive choreography with one another.

A Machine to Be Another gender swap experiment. Courtesy BeAnotherLab

“Let’s face it, most uses of virtual reality in literature and film have been highly dystopic,” Cioffi says. “What matters isn’t the technology, it’s the thinking. It’s the notion that you are talking about artists, makers, thinkers, working in communication and building methods that are about placing you elsewhere. I really believe in my lifetime that it will be decided whether the fundamental driver behind these experiences will be humans or algorithms—so I know what I’d like to work towards.”

Beyond Tom Furness, the man who invented the technology and has been working on it for 50 years, few people in Seattle have thought as deeply about the potential of virtual and augmented reality than Cioffi, who prior to her dive into VR had a long career as an independent filmmaker. She was responsible for this June’s first SIFFX, a four-day virtual-reality and 360 film festival within the Seattle International Film Festival that drew glowing reviews.

The theoretical power of something like virtual reality first occurred to Cioffi in the ’80s as she was filming a documentary with a “big ¾-inch tape-deck video camera” in Nicaragua. Butting against the camera’s limitations, she imagined being able to literally drop someone into her own shoes in that moment, and how much more effective it might be in getting viewers to think.

“I really believed that if the audience could hear the woman I just heard speak to me about terror—talking about the Sandinistas, listening to her saying ‘Your government is funding people that are not elected by anyone, trying to overthrow us’—if people could stand on the Managua street corner and experience this, it would change them,” she says.

Part of her investment in VR, she says, is admitting that the communication device she’s invested so much of her time in, her camera, is “not quite moving us fast enough.” Creating VR films using new 360 cameras that can shoot in all directions at once, she believes, could get us there faster. “It’s this idea of new skin in the game,” she says. “Maybe it’s because currently, with our phone, you know, our robot, it has placed us in this weird realm where everything’s out here,” she says, holding her smartphone far out in front of her. “I don’t have much at risk as I do when I’m actually in it.”

“The empathy machine” is a phrase that gets thrown around a lot in the nascent VR world, a phrase that gained popularity thanks to 360 filmmaker Chris Milk. Milk is responsible for the first-ever virtual-reality film shot for the UN, 2015’s Clouds Over Sidra, which follows a 12-year-old Syrian refugee and her life at the Za’atari camp in Jordan. The film was shown to policymakers and influencers at the 2016 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

“That’s when I first heard VR described as anything besides this new video-game technology,” Seattle filmmaker Lacey Leavitt says of the first time she saw Milk’s TED talk on the project. “To actually put these policymakers [from the WEF] in there where they can put these abstract dollar signs to this actual place they could be inside, that just gave me chills.”

Leavitt and her artistic partner, fellow filmmaker Mischa Jakupcak, were talking about starting a film production company together, but after Leavitt saw Milk’s talk, she knew she had to make the switch to VR. “I was skeptical at first,” Jakupcak says. “Film’s always been my first love and I never assumed anything would rival that, but I’m continually mesmerized the further we go down the road at the capability for emotional impact. I feel like there’s a great power in this moment in who gets invited in to share stories.”

Mechanical Dreams, the duo’s brand-new VR film company, has made it a priority to invite a diverse array of voices into the process. Acknowledging that the vast majority of early-adopter VR headset owners are white males from gaming backgrounds, Mechanical Dreams sees this amorphous early stage of consumer VR as the most opportune moment to assert these voices—hopefully steering the medium’s development in a more just, equitable direction before it suffers the same white, male-dominated fate that film has.

A still from Tracy Rector’s 360 film, Eagle Bone. Courtesy Mechanical Dreams

The duo’s first film, Eagle Bone, was shot in a scrappy two weeks (to meet the deadline for SIFFX) with Seattle indigenous filmmaker and activist Tracy Rector. The gorgeous film, which follows Tlingit artist Nahaan as he reads a spoken-word piece in various Northwest landscapes and ends with a traditional ceremony on a beach, made its international debut last month at the Toronto International Film Festival. Eagle Bone was one of five VR films selected for the festival, alongside comparatively big-budget pieces from Cirque du Soleil and Baobab Studios, a new VR animation studio with ties to Dreamworks and Comcast. Since then, the duo has been busy planting the seeds for a suite of new films with a variety of directors, including award-winning local filmmaker Lynn Shelton and queer African artist Netsanet Tjirongo, whose project Dom: A Story of Rebellion will put you in the shoes of a client of one of Tjirongo’s friends—a black dominatrix.

At SIFFX they met Dacia Saenz, a local queer Hispanic filmmaker they’re partnering with on one of their next endeavors, Experience Pride, a series that will tell the stories of a number of local LGBTQ community figures. “It starts with the darker times people have discriminated against them,” Leavitt says, “but also tells how they came to be where they are now, a part of this community.” The interviews will be interspersed with 3D animations from comic artist (and Seattle Weekly contributor) Robyn Jordan, and end with immersive scenes, some shot on top of a bus, from the most recent Seattle Pride Parade.

“Especially in an immersive medium like this,” Leavitt says, “we don’t want to reinforce this white American view of other parts of the world when we can actually get the experiences and literal perspectives of these people, and let them tell their stories and control how they want to tell them.”

Leavitt and Jakupcak are two early adaptors to this new medium, but part of Cioffi’s push with fearless360° is to bring as many artists like them into the VR fold as possible, as quickly as possible. Cioffi hopes to show the major tech forces behind the hardware, who thus far have invested mostly in video games, the multidisciplinary power VR could wield, and she wants this utopic future to be born in Seattle, a place she has taken to calling the Silicon Rainforest.

“Silicon Rainforest could be the VR/AR of how we live together,” she says, describing a possible project that would simulate the effects of different housing-policy decisions on a Pike Street from the future. “Seattle has an opportunity to be the major player in VR in the meaningful, the nonfiction, the live-action, and the use of world-building for futurism.”

In his own way, Furness has dreamed up something similar, which he’s calling the Virtual World Society. Theoretically seeding money from major tech companies, Furness would hire hackers to develop thematic VR content based on major world problems the UN has identified, acting something like the “Peace Corps of VR”—but even more important, he says, “the conscience of VR.”

It’s something he’s already doing in person. At a recent VR conference Furness spoke at, an excited game developer who saw his talk asked if he would check out their latest VR demo—a car-chase game in which the player wields an Uzi and shoots at a bunch of cops. “The graphics are pretty good,” Furness told them. “But really, is this the best we can do?”

ksears@seattleweekly.com