Maybe this election cycle, with its casual invocation of nuclear war and portraits of American landscapes as dystopian nightmares, will finally break the fever of apocalyptic fiction that has held a tight grip on America’s popular consciousness for well over a decade now. Maybe—and this is one of those predictions that will likely sound very dumb six months from now—maybe it’s time to think about a better future again.

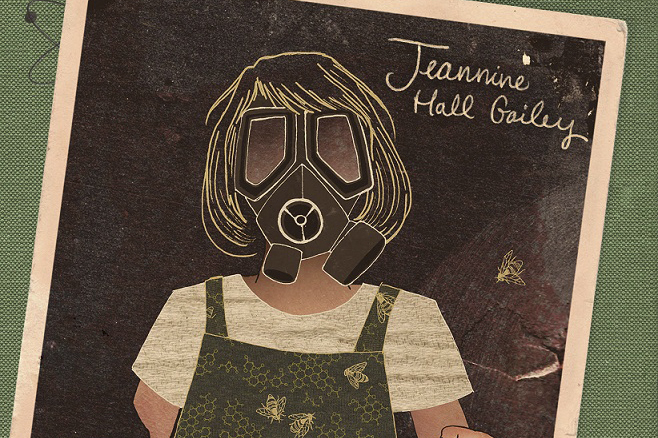

If we are at that moment—if we have arrived at a time to put dystopia behind us—then you can consider Jeannine Hall Gailey’s new poetry collection, Field Guide to the End of the World, as the apocalypse’s Viking funeral, a joyous celebration of all the ways we’ve murdered the world in our imaginations.

I lost count of how many ways the world ended. The first two stanzas alone have four different world-ending possibilities:

While you told me about the bee colony collapse

caused by cell phones or maybe Monsanto and their magic poisons

I was thinking about a friend who said they found a lump

and another friend finishing chemo and waiting for a scan.

That’s two apocalypses that have been promised in headlines—one mysterious, one eminently avoidable—and two apocalypses of a very different kind: a black speck on an X-ray, no larger than a spray of ink smeared on a sheet of white paper by a malfunctioning pen.

But in case you think this is a book just about realistic ways the world can collapse—toxic seas, yawn—you should know Gailey is clearly fluent in dystopia. Just turn to the prose poem “Post-Apocalypse Postcard from the Viceroy Hotel, Santa Monica” for a more Hollywood-ready flavor of doom: I woke up and laid out by the pool, still blue and inviting, the swim-up bar emptied of everything but ice buckets. Oh, for ice. There was something falling from the sky, tiny and white, but it wasn’t snow. It was ashes. Ashes of what?

The luxury of a California hotel, laid low with the forced paucity of an apocalypse, dusted with what might be atomic portions of incinerated human beings falling from the sky: Now we’re getting somewhere!

Gailey understands that these moments are primed for humor, too. In “Martha Stewart’s Guide to Apocalypse Living,” we see the crafty, luxurious upper-middle-class white woman’s take on the genre, with its tips on “storing munitions in attractive wicker boxes.”

Why the end of the world? Why not? What writer isn’t obsessed with that first moment of “not,” when everything we know stops? Like the rest of us, Gailey’s attention has surely been oversaturated with visions of death and desolation. She’s wondered what all that obsession with conclusions can do to a psyche. Her curiosity has driven her, again and again, to the very edge of the end of the world. Unlike most of us, she goes over that edge, into the uncertainty, and she brings something back for us. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St., 633-0811, openpoetrybooks.com. Free. All ages. 4 p.m. Sat., Oct. 15. Paul Constant is the co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. Read daily books coverage like this at seattlereviewofbooks.com.

books@seattleweekly.com