Journalism is inherently a little predatory. You pop into a stranger’s life, ask them probing questions, record what they say, cut 80 percent of it, and then spit it back out with, ideally, as much context as you can, for the whole world to consume. Understanding the power and influence of the Fourth Estate, most folks consent to the weird exchange and have no problem being interviewed—they want their stories told. That’s certainly not always the case, though. Back in 1967, for instance, Canadian TV journalist Hugh O’Connor was shot and killed on assignment in Kentucky by a man named Hobart Ison, who despised the way media outsiders portrayed his Appalachian community.

In 2010, Seattle comics journalist Sarah Glidden went on a two-month trip to Turkey, Syria, and Iraq with her friends Sarah Stuteville and Alex Stonehill, co-founders of the then nascent Seattle Globalist. While Stuteville and Stonehill were out to track down stories about the impact of the U.S. invasion of Iraq on the lives of regular people there, Glidden joined in on a sort of meta-journalistic endeavor—reporting on their reporting. The result, Rolling Blackouts, out this week from Canadian comics giant Drawn & Quarterly, is a graphic novel not only about the stories of refugees in limbo, broken families, and victims of political circumstance in the Middle East, but about the strange, uncomfortable proposition of journalism. To tell the tale, Glidden recorded hundreds of hours of conversation, but she didn’t limit herself to only taping Stuteville and Stonehill’s interviews. She also hit record while the group was at dinner, chatting over beers, hanging out in hotel rooms, and riding to and from cities. According to Glidden’s epilogue, almost all the dialogue, save for a few instances when recording wasn’t possible, come directly from these recordings.

Publishing a “behind the scenes” for most news stories would probably bore 99 percent of the populace to sleep, but in Glidden’s hands, the unusual twice-removed window into the Globalist’s trek offers some incredibly compelling narratives and food for thought. One of the most interesting dynamics throughout the book, one we wouldn’t see without Glidden’s unique perch, is the one between Stuteville and the fourth member of the Globalist’s traveling gang, her childhood friend Dan. A liberal Seattle native raised by antiwar hippie parents, Dan surprised everyone at 25 by joining the Marines and serving a tour in Iraq. At the start of the book, we learn that Dan, now an undergrad at Northeastern University on the GI Bill and eager to get new perspective on the country he helped “liberate,” will join the triad of reporters on the trip for school credit—but also as one of Stuteville’s story subjects. As Stuteville says later in the book, part of what makes a great piece of journalism is that the central figure experiences something and changes because of it. Dan is, to Stuteville’s constant frustration, impervious to her attempts to coax out any such revelations in interviews, maintaining his undramatic position that, while the Iraq War was bad, he did his part to help make positive change there, and doesn’t regret a thing. As Stuteville’s ideal narrative for Dan’s story falls apart, the tension between the two boils over. “I don’t think that I’ve conducted myself perfectly in this and I don’t think there’s a way I could have,” Stuteville says as she and Glidden stand on a balcony in Syria near the end of the trip. “All of those journalistic norms that are usually in place for this very reason weren’t there.” Can you objectively tell the story of a friend?

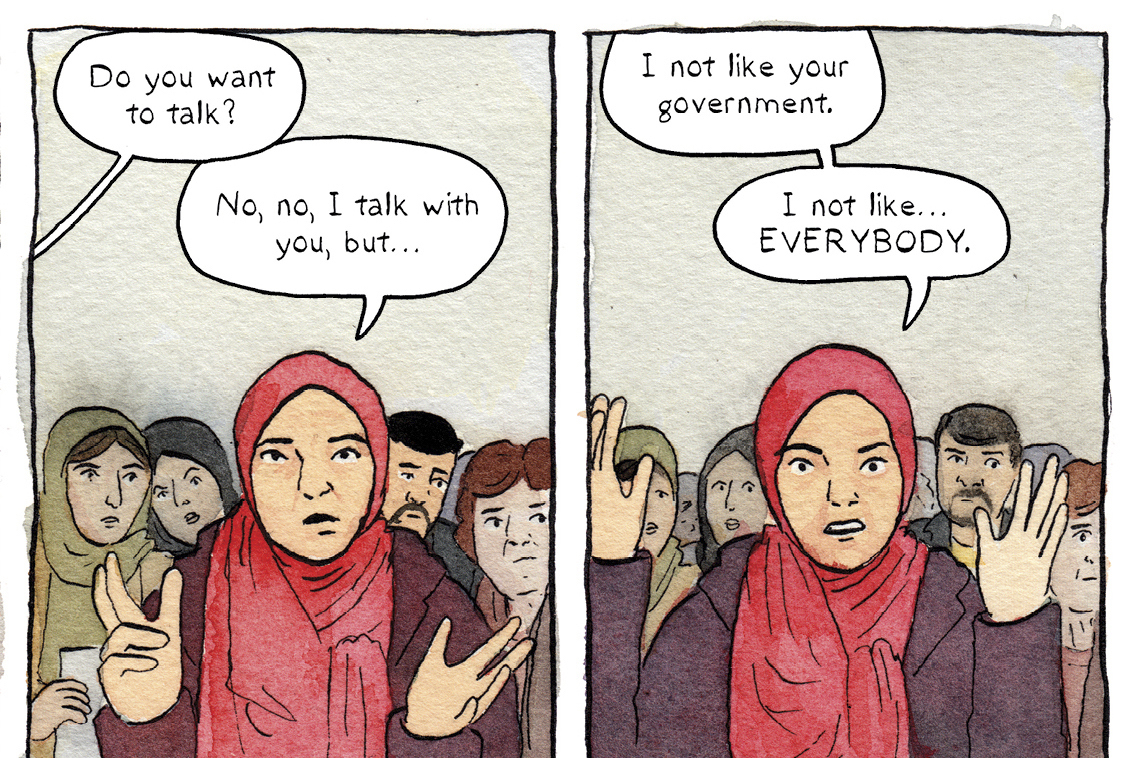

This question also arises in Iraq during the group’s extended interview with Sam, a man who emigrated to Seattle with his family during the war, only to get separated from them and deported back home after accusations that he assisted an Al Qaeda agent at Northgate Mall, a man he swears he encountered only briefly by chance. Despite the war, his poor treatment by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and not being able to see his children, Sam speaks incredibly highly of America and is preternaturally hospitable and kind to the Globalist crew—all of which makes pressing for hard details on the foggy story behind his deportation harder for the reporters. Later, at a Syrian refugee camp, a woman gives the reporters the opposite treatment. Upon finding out they’re American, she begins angrily interviewing them: “I not like your government. What is the benefit of your army coming to Iraq?”

Joe Sacco is indisputably the pioneer of comics journalism, so it’s no coincidence that the cartoonist has helped mentor Glidden during her upstart career in the relatively scant field. Rolling Blackouts is, in this reader’s eyes, however, an example of the pupil surpassing the master. Sacco’s war reporting throughout his work is incredibly detailed and impressive, but his dense writing, busy drawing style, and irregular, always-changing panel layouts made many of his pieces as hard to get through as classic text-only journalism. Glidden’s work, with its consistent nine-panel grid and simple but descriptive line work, is pitch-perfect at turning what would otherwise be a slog into a breezy read, one many readers will probably tear through in a single sitting. Rolling Blackouts Reading, Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave., 624-6600, elliottbaybook.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m. Wed., Oct. 5.

ksears@seattleweekly.com