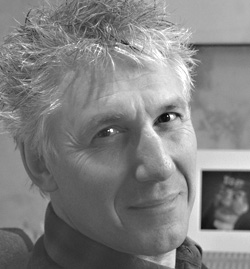

Gian-Carlo Scandiuzzi, ACT’s executive director of new works, was introduced to me through an intriguing document. It’s an internal memo that was written in February by Kurt Beattie, artistic director of ACT, and is generally referred to at the theater as a “manifesto.” That’s a curious title; usually, it’s earnest, young graduate students who are planning to conquer the world through theater, not artistic directors of major regional arts organizations, who write artistic “manifestos.”

Yet, funnily enough, that’s exactly what this memo is: two pages filled with projects and ideas to fill not only ACT’s stages, but also its corridors and lobbies, and not just with plays, but with collaborations with dancers, writers, and visual artists. It’s a vision of transforming the three-stage complex of the old Eagles Building into a nonstop arts center. And the man Beattie’s delegated to transform it is Scandiuzzi.

The friendship between the two goes back to 1983, when the Swiss actor showed up at the Empty Space fresh from drama school in Geneva. Beattie cast him in The Return of Pinocchio, despite the fact that Scandiuzzi barely spoke any English. This led to further collaborations, but soon Scandiuzzi shifted his focus to another passion: music. Along with several friends, he was instrumental in turning the Showbox from a bingo parlor into a showcase for innovative bands, from punk-rock legends like the Ramones and the Dead Kennedys to the Police and Devo.

Scandiuzzi then moved to film, both as an actor (you can see him in several Hollywood pics, including Bugsy and The Public Eye) and as the producer of his own film company, which he ran through the late ’80s and into the ’90s. He’s dismissive of those films now (“they weren’t all that interesting; low-budget sci-fi action, that was our specialty”), but they did give him a hands-on education for his current job: raising cash, and creating relationships, for unlikely art projects.

Scandiuzzi believes that in professional theater, the idea of “new” projects too often is tied to “expensive.” “‘Where’s the budget for that?’ is always the first question. That’s a big dissuader, where we’ll find the money. Here, we’re trying to identify projects that don’t cost a tremendous amount of money, if any at all.”

Any at all? “If we invite in a dance or theater company for a residency, that can just mean that all we’re doing is giving them a space for rehearsal and performance. And that has real value to them. Without them, the space is just sitting there idle.”

None of the projects in what the two men call the Central Heating Lab are traditional plays. “Truthfully, the writing that’s available to us right now isn’t the greatest,” says Beattie. “There are wonderful individual writing talents, and we feature some of them in our mainstage seasons, but the most exciting possibilities to me right now are in community-based work, designers, actors, choreographers, visual artists. Carlo’s a great choice to make that happen. He’s not only experienced, he’s just a happy guy.” (Talk to him for five minutes, and you discover it’s true—you’ll want this man at your next party.)

Although Scandiuzzi has only been at ACT since May, he’s already taken several steps to implement Beattie’s vision. There was a cabaret focusing on the writings of Theodore Roethke that ran in tandem with the solo show First Class, in which musicians and writers produced pieces inspired by the iconoclastic local legend. Then there’s a new relationship with Seattle Dance Project, a company founded by PNB dancers Julie Tobiason and Timothy Lynch, which will feature original pieces performed in and around the building. They’ve also collaborated with local filmmakers Raw Stock to host a mini–film festival, and are forming additional relationships with local visual artists. Most ambitious of all is an oral history project called Highway 99, inspired by a bus trip Beattie took along the strip of road between SeaTac and South Seattle. Playwright Andrea Allen, writer/performer Todd Jefferson Moore, and ACT’s artistic staff are exploring the culture and people of this region of immigrants and transition, gathering stories from its residents to create a theatrical snapshot of an often-ignored community.

While the impulse behind much of this is serious (“there’s an urgency to explore these stories now,” says Beattie, “when our world can seem like an endless catastrophe”), both men seem practically giddy at the possibilities. Scandiuzzi compares it to the exhilaration he felt bringing ban ds to Seattle in the ’80s, groups with no local reputation or radio play. “Thirty years later, this all feels the same. We’re not just producing theater, we’re trying to change the form and its relationship to the community.” He gives another exuberant laugh, then adds, “My batteries are fully charged, and I’m having a ball.”