In some ways, it’s fitting that Seattle is the first stop on the tour of the new Tiffany exhibit—the grand glass smith of the early 20th century visits the town of contemporary glass master Dale Chihuly. And Tiffany’s evident fascination with water and nature seems at home in the watery landscapes of the Pacific Northwest: Stained-glass koi gape and flip through fragmented blue-green currents, fiery-eyed dragonflies suspend and glow from lampshades, while nebulous sea creatures drift and bubble up through windows and bowls. Yet, this is an oddly subdued show for the occasion—Seattle Art Museum’s last exhibit in its downtown location until 2007.

There’s no denying the allure of “Louis Comfort Tiffany: Artist for the Ages” (through Jan. 4, 2006; 206-654-3100, www.seattleartmuseum.org). Over 120 rarely seen items demonstrate the range of media the American artist explored—enamel, pottery, bronze, as well as his famed leaded glass and self-coined Favrile glass that sometimes glistens with metallic shimmers, other times is so opaque it almost looks as if it’s made of ceramic or stone.

Much to his famous father’s disappointment, Louis C. Tiffany (1848–1933) chose not to join the family jewelry business, but instead started off as a painter. He switched to interior design and focused on glass as a decorative medium. There he found his calling, ultimately as the creator of the brilliant leaded glass windows and the much-imitated lamps for which he became famous. His innovative techniques layered multiple panes of glass so that colors bled through each other, creating rich textures and playing with light in new ways.

A man of both artistic and entrepreneurial vision, Tiffany never blew glass or made any lamps himself, but he hired teams of talented artisans (at one point over 300) to execute his techniques and ideas, paying them well and giving them credit when due. His standards were demanding. “He was known to have gone through workshops smashing objects that didn’t meet his criteria,” says exhibit curator Marilynn Johnson (formerly the associate curator for the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

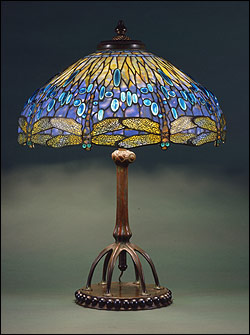

The classic pieces he is known for are worth seeing for their craftwork and famed translucence—the flower-form vases, an intricate bronze lamp dripping with glass wisteria (designed by Mrs. Curtis Freshel in 1901 and produced by Tiffany Studios), a voluptuous Persian rosewater sprinkler. Each exquisite item is well displayed and lit to a fine glow.

More interesting, though, are the objects that aren’t obviously beautiful, like the bulbous “Lava” vases from 1915 and 1918, a cluster of enamel and copper mushrooms that form an inkstand, or the strange membranous plaque that resembles an invertebrate under a microscope or the imprint of a sand dollar. There are also unexpected pieces that most people wouldn’t normally associate with Tiffany—a wrought-iron fire screen made of linked chains of glass tiles evoking ancient Chinese armor, and a crazy little swatch of “spiderweb” wallpaper on which clover flowers are entangled in inky webs.

There’s no question that great artistry and technique are evident here, but in choosing this exhibit as its grand finale before closing for a year on Jan. 4, 2006, during its expansion, SAM has opted to go out, not with a bang, but with an elegant whisper. And it’s hard not to wonder if this wasn’t a missed opportunity.

Why not leave people with something provocative that resonates more cogently with the current times? Something that looks forward, instead of back?

In a way, the timing of this exhibit is ironic. Our current era of man-made and natural disasters has more in common with the time when Tiffany’s luxurious work fell into disfavor—the years of war and Depression shortly before he died in 1933.

“Artist for the Ages” is the exhibit subtitle. But how does this art speak to our own troubled age? Perhaps nostalgia is primarily what one can take from this show. For some that may be enough. But hopefully the new SAM will offer us a little more.