Friends, readers, and thespians, lend me your ears; I come neither to bury Chamber Julius Caesar (Seattle Shakespeare Company’s current production, that is) nor to praise it. Somewhere in between, actually, perhaps a little of both. As a big fan of chamber productions in general, I would’ve been pleased simply to see a straight-up and streamlined rendition of this great historical drama, which recounts the political chicanery and conspiratorial plotting that leads to the slaying of the powerful and popular Julius Caesar (Andrew McGinn) by a hoodwinked Brutus (David Quicksall) and his devious henchmen (and henchwomen, in this adaptation)—most particularly Cassius (Hana Lass) and Casca (Brandon Simmons). A play this masterly and magnificent, no matter how well-known, needs no frills, no shaking up; it retains at its core an elemental force, and even in a chamber format, Julius Caesar should storm the stage with all the brutality and violent beauty of the coup d’état it portrays.

If, however, one chooses to futz with the historical trappings, as does director Gregg Loughridge (whose previous SSC production turned Richard III into a muscular parable of modern corporate corruption), it would be well to keep to a single theme. The problem with this Caesar, far from disastrous but hindering nonetheless, is the attempt to blend two apparently incompatible elements. In Loughridge’s hands, Rome becomes a combination martial-arts dojo and incestuous spiritual commune—though the latter aspect comes across less as a Zen community than as a rabble given to the posturing, cheerleading, and hoo-hawing of a Maury Povich talk-show studio audience.

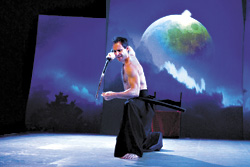

The juxtaposition is odd—not exactly oil and water, perhaps, but a confusing thematic dissonance jarring enough to often diminish the play’s raw power. The production opens with Brandon Simmons leading the audience in a call-and-response cheer (“Lupercal! Lupercal!”): undeniably comical, it sets a raucous, slyly irreverent tone. This sort of reality-TV populism is strung throughout (at one point, Simmons’ sing-along degenerates into the Beatles’ “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”) and is used most effectively to exhibit the ovine fickleness of the masses, whose political leanings are at the mercy of the latest rhetorical flourish. Had Loughridge stuck with, and fully developed, this comic conceit, Caesar might have worked as a biting satire or absurdist parody of contemporary politics. As it stands, the device seems a bit half-baked; coupled with the dojo-samurai groove of obis and swordplay (Quicksall delivers Brutus’ bedroom soliloquy while running though a series of shirtless tai-chi-like exercises), the whole thing becomes a bit half-assed and lacking in unity of vision and execution.

Still, Loughridge is obviously talented, and this production definitely has its moments. As he proved in the more solidly conceived and successful Richard III, Loughridge has a knack for creating a pervasive atmosphere of brooding menace and suspense; the tense minutes leading to and directly following Caesar’s execution are especially captivating. He’s aided by solid performances in all the right places, most notably those of Quicksall and McGinn, who has a quietly charismatic presence and a lovely voice. Kelly Kitchens gives Portia a solemn intensity, and Kate Witt is also good as Calpurnia and Octavius. As Antony, David Hogan at times pushes a bit too hard, almost overplaying the crucial funeral oration at the play’s heart, though sharp comic timing and the smart, knowing look he wears save it from schmaltz. None of the actors really soar, but the cast is professional and proficient, if at times seemingly unsure about this adaptation’s overall thrust or tone—is it reaching for comedy? Satire? A bristly comment on mass culture? Or maybe a jibe at the Californication of politics, with its rampant consensus building and here-today, gone-tomorrow identity worship? It’s hard to tell.

Seattle Shakespeare Company is trying something new by rotating productions on a seven-day-a-week schedule through January: Chamber Julius Caesar runs Thursday through Sunday, while Patrick Page’s Swansong, directed by SSC’s artistic director, Stephanie Shine, plays Monday through Wednesday. It’s a cool move from a number of perspectives, though the rigors of double duty, in terms of manpower, preparation, and such, could account for Caesar‘s apparent lack of focus and artistic integrity (in the most technical sense). If this is the case, it’s difficult to say whether the sacrifice is worth it. It’s tough all around for repertory theaters, with artistic ambitions in a continual tug-of-war with fiscal feasibility. The twofer gambit may lean a little too heavily on the latter, giving the former a tough run for its money.