PICTURES NEVER DO justice to art, but photography is especially poor at capturing an installation, which relies heavily on the physicalities of the gallery space and the viewer’s movements within. Of course, that’s another way of saying that your efforts will be rewarded should you see Richard Kraft’s and Joseph Biel’s collaborative installation in person. Theirs is an impressive, if enigmatic, exhibit that offers much to contemplate.

Installation by Richard Kraft and Joseph Biel

Greg Kucera Gallery, ends July 29

The Portland duo has transformed the Greg Kucera Gallery into a surreal dreamscape: An iron-frame bed guards the entrance, and above it a red model airplane whirs around in a circle. A few feet away, a statue of a soldier stands atop a pedestal. Each object almost looks as if it could be part of a boy’s bedroom, except that the bed sits precariously on overturned silver chalices and the plane becomes a bit menacing in its constant circumnavigation.

Comprised of many disparate objects (all of which vary in scale and density), the exhibit conveys the sense that the viewer is participating in a stream-of-consciousness—that’s just one possible explanation for how such unrelated objects are displayed together. We think there must be some sort of order in the objects’ placement in this space, as well as a psychological significance.

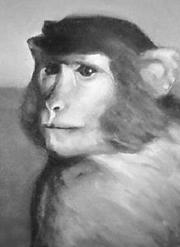

The gallery’s back room houses a grid of nearly 400 ink-jet images of personal and general import: A photo of Biel’s girlfriend mingles with pictures of Itzhak Rabin, soldiers carrying a coffin on their shoulders, nuclear plants, illustrations from Marquis de Sade texts. There’s also a striking oil painting of a monkey, its head-and-shoulders view and cautious expression oddly reminiscent of a Van Gogh self-portrait.

ONE APPROACH TO this complex exhibit is to group objects according to theme. Some, for example, refer to WWII and the Holocaust: the plastic-cast German soldiers; the airplane; a large photo of a Hasidic Jew; and, most impressive, a long shelf of cigarettes rolled in pages from the New Testament. (Unfortunately, because of the toxic ink, the artists do not “perform” by smoking the cigarettes). Yet Kraft and Biel, who are both Jewish, play more loosely with the intersections between personal and global histories.

Biel says he was going for the effect of a Bruegel painting, where many “little worlds” seem to exist in each square foot of the canvas—and that is what the viewer ends up doing, linking two or three things together into comprehensible spheres. But what eventually pulls everything together is the gallery floor. The artists have covered the main space with sheets of heavy-gauge copper, which casts reflections of the objects and fills in the empty spaces. It also records the foot traffic during the show’s run—on First Thursday, plenty of scuffs and shoe prints (even paw prints!) were left for posterity. The artists plan to use the copper sheets for a future intaglio print edition, so when you go to the gallery make sure to wear your hiking boots.