LOU HARRISON MADE his mark on American music by looking west rather than east. While other composers in the ’40s and ’50s were busy arguing Stravinskyan neoclassicism vs. Schoenbergian serialismnever realizing that Europe wasn’t the only answerHarrison was inspired by Asia, primarily the Indonesian gamelan (percussion orchestra), helping to open Western concert music to the world’s vast musical richness.

Next week, a pair of concerts, organized by Harrison’s friend and colleague Jarrad Powell, leader of Gamelan Pacifica at Cornish, will memorialize the recently deceased composer (8 p.m. Fri., Nov. 21, and Sat., Nov. 22, at Cornish College of the Arts, 206-325-6500). Those performances will be preceded by two warm-up events, creating a serendipitous Harrison mini-festival: The Seattle New Music Ensemble will play The Perilous Chapel (1949) for flute, harp, cello, and percussion (7:30 p.m. Wed., Nov. 12, at Town Hall, 206-533-0347), and the Seattle Chamber Players will include Harrison’s 1939 First Concerto for Flute and Percussion on an all-American program (7 p.m. Sun., Nov. 16, at Benaroya Hall, 206-286-5052).

Cornish is an appropriate home for a memorial concert. It was at Harrison’s recommendation that John Cage took a job there in 1938 as an accompanist in Cornish’s dance department (Harrison was working for the dance department at Oakland’s Mills College). In turn, Cage invited Harrison to compose for his experimental percussion recitals here, encouraging Harrison in his recent discoveries in Indonesian music. Eventually, Harrison not only drew on the gamelan’s sound world delicate metallic timbres, idiomatic scales and tuning systems, gently revolving rhythmic organizationin his music for traditional Western instruments, he learned to build and compose directly for gamelan itself. Three of the works in these Cornish concerts involve Gamelan Pacifica in combination with a soloist: violinist Karen Iglitzin in Philemon and Baukis (1987); violist Eyvind Kang in Threnody for Carlos Chavez (1978); and vocalist Jessika Kenney in A Soedjaymoko Set (1989), a setting of a text from the Hindu epic Ramayana.

Born in Portland in 1917, Harrison spent his whole life on the West Coast, save for a decade in New York (when he worked as a music criticone of Virgil Thomson’s stringers at the Herald Tribune along with Cage and Paul Bowles). Cornish’s Jarrad Powell sums up the many facets of Harrison’s radicalism: “[He] chose to work outside the mainstream, lived away from the main cultural centers, formed his alliance with world music very early on, eschewed the dominant cultural poses and stances vis-୶is musical style, and testified with unabashed enthusiasm to the sensual qualities of music.”

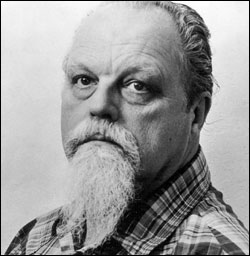

Ebullient and rotund, looking a bit like Santa Claus’ countercultural younger brother, Harrison was a polymath whose breadth of interests and skills were matched by very few composersonly Bernstein and Britten, perhaps, among his contemporaries. He studied early music; when he was in a European mood, his music evoked medieval dances and baroque suites. He researched alternative tuning systems, composing in ancient Greek modes as well as traditional Indonesian ones. He relished working with dancers. He was a conductor and music editor, best remembered for preparing and premiering Charles Ives’ Third Symphony 40 years after its composition.

He was an outspoken pacifist, a frank, unself-conscious gay man, and an indefatigable “writer of letters to the editor,” as he put it, on both these topics. He was a student of Esperanto, a calligrapher, a designer of fonts. And he mentored younger composers generously and tirelessly: It was en route to yet another college music festival that Harrison diedin the parking lot of a Lafayette, Ind., Denny’slast February. Perhaps above all, Harrison demonstrated to late-20th-century composers (many of whom had forgotten) that a probing curiosity and enthusiasm for experiment are not at all incompatible with the pursuit of aural beauty.