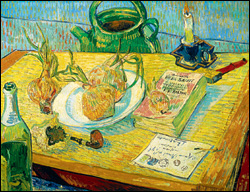

What does one receive standing in front of a Van Gogh?

Seattle has the opportunity to find out this summer as the Seattle Art Museum hosts a stellar collection of paintings by the Dutch artist and other modernists from the collection of Holland’s Kröller-Müller Museum.

Most of us are familiar with the Van Gogh myth: poverty, madness, unappreciated genius, suicide (not to mention Kirk Douglas in Lust for Life). It’s hard to separate the circumstances of Van Gogh’s life from his work, in part because of the astonishing letters he left behind. Had all Van Gogh’s paintings burned and only his letters remained, his reputation would still be secure.

Nowadays that reputation has ballooned into Van Gogh the cultural phenomenon. He’s a celebrity. Any one of his paintings, if put on the market today, would probably outstrip the $104 million recently paid for a mediocre Picasso. Everything from vodka to banking services is named for him. Elizabeth Taylor, for god’s sake, is embroiled in a fight with Holocaust victims over whether her Van Gogh was looted by the Nazis.

SAM’s “Van Gogh to Mondrian” is a rich collection, and the museum is lucky to have it (the exhibit travels to the High Museum of Atlanta before returning home). You can gawk to your heart’s content at a slew of famous Van Goghs, including an 1887 self-portrait and the iconic Café Terrace at Night. But equally rewarding are the more obscure pieces, including Tree Trunks in the Grass from 1890, a Jackson Pollock–like orgasm of paint: blue iris exploding on the horizon, an omnipresent yellow sun blessing all, and a gorgeous tree trunk rippled with tortuous strokes of ochre, cadmium, and Prussian blue.

Lest we forget, there are other painters of note in this sampling from the Kröller-Müller, including several pointillists such as Georges Seurat (though I’ve always found pointillism overly fussy). Cubists Fernand Leger and Juan Gris are well represented, and there’s a fabulously freaky pair of mythological paintings by Odilon Redon, two Picassos (including a brilliant 1907 nude study), and seven strong works by Piet Mondrian (whom the Kröller-Müllers supported early in his career, until he became, for their tastes, too “decorative”).

This is a show of high modernism, that great romantic fiction personified in the Van Gogh archetype: the rebel artist, a law unto himself, creator sui generis flailing at the world and his canvas. Of course, reality was a bit more nuanced. Van Gogh was well-versed in the works of his predecessors and every bit a traditionalist when it came to religion. Far from being an aesthetic rebel, Van Gogh recognized he was part of a continuum that stretched from Giotto to Delacroix. Yet modernism continues to be a noble and useful fiction, giving artists license to live and create on their own terms.

So what does one receive standing in front of a Van Gogh?

The drawing Wheat Field With Sun and Clouds holds a clue. It was sketched behind the locked doors of the asylum at Saint-Remy in 1889, not long before the painter’s death. Scratched out in the depths of despair, the picture includes a trademark trembling sun, shimmering wheat fields, and scudding clouds. The drawing captures the penetrating light of southern France that so stirred Van Gogh.

The picture is sublime. It has a beauty that transcends jaded contemporary-art attitudes, mountains of hype, and the latest Baby Van Gogh videos, Van Gogh perfume, and Van Gogh martinis. It gives us something, quite simply, that makes life seem worth living.

“Van Gogh to Mondrian: Modern Art From the Kröller-Müller Museum” shows at SAM through Sept. 12.