ARTISTS REVEAL themselves most through their work. And Martin Amis has written the memoirs that prove it.

To anyone who’s read his brilliant and hilarious novels, this account of Amis’ “experience” will add little to your understanding of the man. Most of the themes he touches upon here have been broached elsewhere. Nor does the book offer much in the way of straight autobiography. Indeed, it’s written as if you’re already well versed in the tabloid highlights of his life, which have been faithfully—and, of course, unfairly— recounted in Britain’s literary-minded media. The feuds, the failed marriage, the illegitimate daughter, the brouhaha over his big-money contracts—Amis assumes you’re plenty familiar with all that, and he doesn’t have a whole lot to say about it. On the whole, there’s remarkably little of the kind of “dish” you might expect from a Tina Brown project.

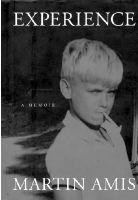

Experience

by Martin Amis (Talk Miramax, $23.95)

But to my mind, these are all points in the book’s favor. What’s clear from Experience is that, even in his own mind, Amis is a writer first and a man second. “[T]he fit reader, the ideal reader, regards a writer’s life as just an interesting extra,” he writes. “On good days . . . this is what a writer’s life actually feels like.” Instead of narrative, we get an entertaining, if uneven, pastiche of thoughts, anecdotes, and literary opinions that follow no particular organizing principle other than the path of the author’s own caustically intelligent mind. In his usual championship-quality prose, Amis dissects a few of his principal obsessions: among them, his father, his father figure (Saul Bellow), language, and his teeth.

The latter topic provides some of the funniest, most memorable passages of the book. Toothaches, bridge replacements, and oral agony have been at the center of Amis’ adult life, and he offers some hideously comic accounts of his torments in the chair, such as the removal of his upper teeth: “The hands of Mike Szabatura, with the horseshoe now wedged against my palate, bear down, and tug. In the rhythmical creaking something gives and something catches. . . . Another trio of injections. And Millie is close, with her rinser, her vacuum cleaner, her masked face. A further San Andreas of wrenching and tearing—of ecstatic sundering. . . . The aromatic hands of Mike Szabatura are now exerting decisive force. And it is gone—the gory remnant whisked from my sight like some terrible misadventure from the Delivery Room.” Later, in the bathroom mirror, his mouth opens to reveal “a darkness, a void, a tunnel that led all the way to my extinction.”

AMIS’ REFLECTIONS on his father, the famed English novelist Kingsley Amis, permeate Experience; we actually learn more personal details about him than about his son. But you needn’t be especially interested in Kingsley to be moved by this loving character portrait, which is resolutely honest and without judgment. Amis portrays his father as a stinging social critic who was afraid of being alone, a charming drinker and hopeless drunk, and, above all, a fierce guardian of the literary word who taught his son love of language. (Amis writes with greatest energy about words themselves—romping, in unacademic style, among passages from Nabokov, Joyce, Larkin, Bellow, and, most of all, his father.) The last third of the book is loosely centered around Kingsley’s death, about which Amis writes with his best kind of clear-eyed compassion and self-reflection.

By contrast, Amis’ encomiums to Saul Bellow, his adopted father figure, quickly become forced and tedious. (“This book is numinous,” he writes of Bellow’s most recent novel, Ravelstein; a few pages later we’re hearing again about “the radiance of the novel Ravelstein. . . .”) Amis is a great literary appreciator, but this sort of personal reverence doesn’t suit him.

Nor does vindictiveness. Like his father, Amis is a master of the one-off put-down— “a laconic, unsmiling, dumpty-shaped tightwad” is how he dispatches his mother’s second husband—but the chapter-long screed against journalists with which Experience ends is an unfortunate misstep. Nobody who isn’t exhaustively schooled in the various controversies surrounding the press coverage of Kingsley’s death will even understand what most of this about. But worse, the appendix undermines the integrity of a memoir that, refreshingly, has much more on its mind than rehashing events, apportioning blame, or settling scores.