IN EVERY HERO’S story there are wildly improbable coincidences that reinforce his mythical stature. It is only fitting, therefore, that Morris Graves, the great painter hailed by adoring locals as a myth in his own time, was greeted in death on May 5 by two uncanny occurrences. The first took place within minutes of his passing. Graves’ friend and caregiver, Robert Yarber, reported hearing the mournful cry of a great blue heron just as the 90-year-old slipped away. Then, within a week, Graves’ longtime dwelling outside Anacortes, “The Rock,” went up in flames.

It’s rare that an artist gains celebrity status, let alone mythical status. But Graves, the last survivor of the group of painters known as the “Northwest Mystics”—which included Mark Tobey, Kenneth Callahan, and Guy Anderson—attained both. At 32, he became the first of his colleagues to achieve national recognition when 30 of his paintings were included in a 1942 Museum of Modern Art exhibition. His success mushroomed from there. Informed by Eastern philosophies, cubism, surrealism, Richard Fuller’s ancient art collection at the Seattle Art Museum, and fellow Northwest painters, Graves’ work illustrates the awe that he had for nature’s marvels but also alludes to their ability to transcend the physical. He kept to simple subjects, such as birds and flowers, and imbued them with cosmic gravity. He once told a friend that he’d “never again take a bodily form.”

Graves was born in 1910, one of eight children. At 18 he shipped out as a merchant seaman and got a taste for Pacific Rim cultures, which eventually shaped his aesthetic and philosophies. After World War II he lived in a series of houses in isolated locations—near Anacortes, near Edmonds, in Ireland, and, finally, “The Lake,” near Eureka, Calif.—since he required quiet and privacy to paint. As his friend of 30 years, the local artist Charles Krafft (a self-proclaimed “slavish Graves sycophant”), explained in a recent interview, “These piss-elegant houses also became theaters where he staged a sort of ‘Graves the Sage’ show once he’d become a celebrity and the world beat a path to his door.” A notorious hermit, Graves was not detached from his success. As Krafft put it, “He enjoyed and managed it with the flamboyance of an arrogant symphony orchestra conductor.”

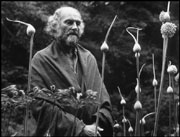

Openly gay, Graves was extremely handsome—tall, dark, and masculine. According to close friend Jan Thompson, who worked at Foster White Gallery for many years, he was a man of extremes: He could fly into a rage, but his kind gestures were spontaneous and grand. His generosity toward those he liked knew no bounds—he’d buy a house for a friend, fund their travels, and was known to put up hosts of San Francisco hippies who made pilgrimages to his hallowed estate. But he remained camera- shy and guardedly private to the end.

AS A YOUNG man, Graves was known to stage madcap displays with a dadaist relish for the absurd. He is said to have rolled out a red carpet in front of himself as he entered a Seattle diner, his grand entrance culminating in a request for a humble lettuce sandwich. Another account describes the spectacle he made of picking up a friend, painter Malcolm Roberts, from his job at a downtown florist’s shop in the late 1930s. Double-parking his beater Model-T pickup on Fifth Avenue during rush hour, he’d roll out the same red carpet to usher his friend to the passenger seat.

Anacortes painter Anne Martin McCool once started to explain the composition of one of her paintings to Graves, pointing out the shape of a mountain. Graves stopped her. He instructed her to kneel down in the middle of the room and examine a sculpture of his. Crouched beside her, he paused and then finally said. “Never explain anything.”

But Graves spent much of his time attempting to fathom life and existence. Krafft, who in 1991 founded a not-so- secret fraternal order called the Mystic Sons of Morris Graves, recalled: “The last thing Morris tried to explain to me was his notion that ‘The opposite of life isn’t death. The opposite of life is time.’ I’m still mystified by this pronouncement, which made perfect and obvious sense to him.”

Morris Graves’ transcendentalism is famous and is evidenced in his charmingly totemic and atmospheric paintings, but he was also known to relish a hearty laugh. He once said, “I began by saying that, as a painter, I am aware of the sky of the mind. In concluding, I would like to remind us each of the other two languages that all humanity shares: the secret language of silence, and the second language we all share is laughter.”