Opening ThisWeek

The End of Time

Runs Fri., Feb. 7–Thurs., Feb. 13 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 114 minutes.

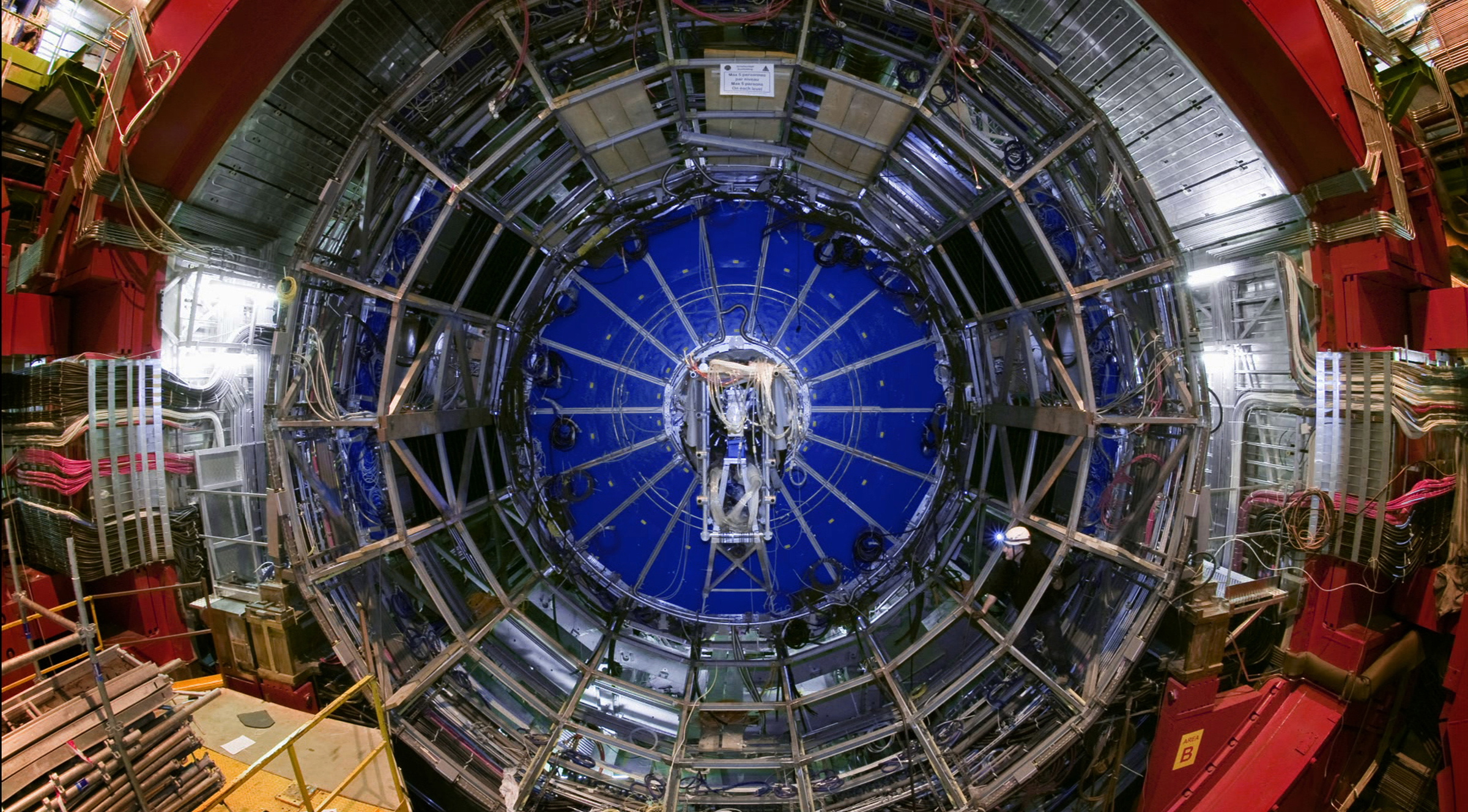

Peter Mettler’s inquisitive doc clocks in at a non-tedious 114 minutes of philosophy, but there are other units of temporal measurement. In the bowls of the CERN particle accelerator in Switzerland, this film would be considered an eternity, since its scientists are studying sub-atomic bits of the most ephemeral nature. In a Hawaiian suburb gradually being overrun by lava flows, The End of Time wouldn’t even register as a blink—it’s as geologically insignificant as Mettler or the moviegoer or all recorded human history. In crumbling Detroit, which Mettler also visits, no one would even have time to watch such a ruminative doc—it’s unclear if any art-house cinemas are even left there.

So there are different ways of thinking about time, and Mettler sets some lovely images to his musings (“The Earth will heal itself; humans will be gone”) and borrowed aphorisms (“In many languages, time and weather is the same word”). The effect of this rambling essay film is like a TED talk crossed with Coachella: educational, but reaching toward the ecstatic—a loss of awareness of time. Mettler also visits Bodhgaya, India, to watch meditation sessions and corpses being burned. “If you have a beginning, there is always a problem,” says one Buddhist sage. Cut to time-lapse skies with a lulling electronica score. Dude, whoa.

With prior documentary titles including Gambling, Gods and LSD, Mettler is working somewhere in the trip-film continuum traced from 2001 to Koyaanisqatsi. He’s not a scientist, more of a cosmic speculator or aggregator. If time is a subjective notion, that means it can be defined in myriad ways, and no one—not even the director—gets the final word on the subject. The chalkboard fills up, until the director’s aged mother renders her verdict on the meaning of time. She rejects a conceptual framework, saying instead, “We have to make the most of [time]. Enjoy everything possible.” Yes, but there are other ways of enjoying 114 minutes. Brian

Miller

A Field in England

Runs Fri., Feb. 7–Thurs., Feb. 13 at SIFF Film Center and SIFF Cinema Uptown. Not rated. 90 minutes.

Anyone innocently wandering into A Field in England can be forgiven for thinking they’ve stepped through a time portal to the late ’60s. Along with its arty approach and unexplained allegorical premise, the movie explodes into full-on psychedelia after a certain stage—all the weirder for being in black-and-white. One wants to summon a few reference points, but even this is challenging. The movie’s a little Waiting for Godot and a little Magical Mystery Tour, with Vincent Price’s character from Witchfinder General hanging around. We should invoke Monty Python, too, for the film’s grubbiness and catch-all social criticism. (Had they been younger, the surviving Pythons might’ve made a fine cast for this.)

The actual setting has nothing to do with Swinging London; the film’s summary says it’s set in the mid-17th century, so that’s what we’ll go with. All of the action takes place in featureless fields, where a small group of soldiers trudges along after fleeing a battle. The most talkative of them, Whitehead (Reece Shearsmith), is actually no soldier, but a scholarly servant out doing the bidding of his unseen “master.” He and his filthy fellow deserters fall under the sway of an Irishman named O’Neil (Michael Smiley), who claims to be an alchemist and says that if they begin digging holes in the field, they will find gold. This goal, clearly absurd, is enough to define this temporary five-man social experiment.

Director Ben Wheatley (Down Terrace, Sightseers), working with screenwriter and frequent collaborator Amy Jump, creates a distinctive world, that’s certain. Like many British artists, Wheatley is obsessed with the subject of Englishness, and he leaves no class or type unscathed. So the movie probably has more sock for UK viewers, to say nothing of the fact—for this hearing-impaired Yank, at least—that maybe a third of the dialogue is unintelligible. (At least the trippiest stroboscopic parts, however migraine-inducing, are without dialogue.) Speaking of the psychedelics, it’s typical of this film’s puzzling storytelling that we can’t be quite sure when things go off the even keel. The fellows ingest their first stewed mushrooms fairly early on, which could explain the curious arrival of O’Neil—tied up at the end of a thick rope attached to a tribal-looking post?—and other such happenings. The maddening thing is that for all the film’s doodling, occasional moments are genuinely funny or haunting. Whitehead’s slow-motion stumble out of O’Neil’s pitched tent, where something unspeakable has just happened, is A Field in England at its best: arresting, druggy, and mystifying. Robert Horton

PGloria

Opens Fri., Feb. 7 at Sundance and Meridian. Rated R. 110 minutes.

Gloria sings along to oldies on the car radio. Everybody does—especially in movies—but for Gloria, a divorced lady nearing 60, singing along seems like an especially cherished private celebration. The rest of her life is less well-ordered than those well-crafted pop songs: Her grown kids are kind but aloof; her new romantic relationship is mystifying; and this hairless cat keeps showing up in her apartment. Gloria, Chile’s official submission to the Academy Awards (it didn’t get nominated), is the film that comes out of this very specific character, and it succeeds because of its well-chosen vignettes and a remarkable lead performance.

Paulina Garcia—a veteran of Chilean television—plays the title role, and she builds a small masterpiece out of Gloria’s behavioral tics. Garcia understands this woman from the heels up: the guarded smile at social dances, conveying her interest in meeting someone but also her wariness at getting duped; the habit of idly cleaning crumbs from the table of her son’s home; the forced casualness of ordering a drink at a bar when she suspects she might have been abandoned there by her date. Gloria has a couple of purely sexual encounters during the film (the movie is admirably nonchalant about suggesting that people over 50 might enjoy a fling or two, and unembarrassed about depicting such flings), but her main romantic interest is a recently divorced ex-Navy retiree, Rodolfo (Sergio Hernandez). He’s boyishly delighted by Gloria’s sense of fun, but his adherence to a certain code of machismo has him hopelessly at the beck and call of his ex-wife and two adult daughters. Formerly tubby, Rodolfo has had gastric bypass surgery and is just beginning to try out his life as a chick magnet. Maybe he misses his protective layer, or he still lacks willpower; whatever it is, he keeps disappointing Gloria.

Director Sebastian Lelio fills Gloria with colorful detail, to the point of occasional pushiness. We didn’t need to see Gloria encounter a peacock at a garden party to infer that she herself might be ready to bloom, for instance. But he and Garcia have created a character so richly imperfect and fully inhabited that her trajectory remains engaging despite the occasional overstatement. By the end, she’s earned her own song (for ’80s pop-music fans, the choice is obvious but still exhilarating); and this time everybody else gets to sing along, too. Robert Horton

Interior. Leather Bar.

10 p.m. Fri. & Sat.; 8:45 p.m. Thurs. Feb. 13; 10 p.m. Sat., Feb. 15 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 70 minutes.

Co-directors James Franco and Travis Mathews, learning that 40 minutes had been censored from William Friedkin’s incendiary 1980 film Cruising, decided to remake/reimagine them. We see some of those completed scenes, but basically this is a making-of doc—in other words, we are watching Franco’s footage of Mathews filming actor Val Lauren playing Al Pacino playing undercover cop Steve Burns playing gay. To recreate the discomfort Pacino’s character (and presumably Pacino himself) felt while shooting the original steamy S&M-bar scenes, they naturally had to cast a straight actor in the role. (After we see Lauren and his fellow thespians receive a lesson on how to cruise, it becomes amusingly clear they needn’t have bothered—the attitude and body language of a gay man on the prowl in a club is identical to an actor’s habitual, perpetual how-do-I-look self-consciousness.)

For a working actor, Lauren’s surprisingly unworldly, and consequently Interior. Leather Bar. is primarily an exploration of his personal conflict over all this scary gay stuff. On the phone with Lauren, we hear his agent’s harangues, warning him of the damage to his reputation that’ll be done by “Franco’s faggot project.” (Because of course after Cruising, Pacino’s career tanked.) Since Franco’s stated motivation for this exercise was a demand for the freedom to explore sexuality on film, and since the unseen agent’s homophobia thus lies at the crux of the issue, it’s odd that these conversations are the scenes that ring falsest; and when we later see Lauren sitting against the wall of a parking lot, his script in his lap, reading aloud the stage direction “Val sits against the wall of the parking lot. The script is in his lap. He reads to himself,” you suspect the entire thing—in yet another layer of meta—is a fully scripted put-on. (What’s not simulated is the close-up fellatio; take this either as warning or encouragement.) Also see Steve Wiecking’s take on both movies, page 19.

Gavin Borchert

The Monuments Men

Opens Fri., Feb. 7 at Ark Lodge and other Theaters. Rated PG-13. 112 minutes.

Start reading about the Allied military unit charged with finding and securing the stolen artworks of World War II, and you will happily disappear into fascinating stories of heroism in the face of Nazi treachery. The 2006 documentary The Rape of Europa stirringly recounts part of the saga, and is a good starting point for further inquiry. George Clooney’s movie, inspired by the unit, is a sincere if unwieldy plea for art as a vital human resource, but The Monuments Men can’t quite do justice to the tale.

Clooney first appears as Danny Ocean with professorial beard: Frank Stokes, a museum curator with FDR’s approval to assemble a crack team of art experts for active duty. As a filmmaker (he co-wrote with frequent partner Grant Heslov), Clooney knows he can’t entirely escape the air of the Ocean’s Eleven pictures, so he doesn’t try; the all-star assembly this time returns Matt Damon to the ranks, with new enlistees Bill Murray, Jean Dujardin (the Oscar winner for The Artist), Bob Balaban, and John Goodman. On the theory that professors and art experts are probably less colorful than jewel thieves, Clooney sprints through the recruitment process, getting the Monuments Men to the front lines where they can hunt for hidden masterpieces and crack a few jokes. The old-fashioned humor includes some kidding-in-the-face-of-possible-death, suggesting that Clooney has recently enjoyed a few Howard Hawks pictures. Meanwhile, a subplot involving Hugh (Downton Abbey) Bonneville’s disgraced British curator has an agreeable old-Hollywood simplicity— Clooney could be trying to make a movie that really might’ve been produced in the 1940s.

The problems come when Clooney tries to weave his jocular mood together with intimations of the Holocaust and periodic speeches—there are at least two too many—in which we hear about how the art saved by the Monuments Men really was worth the effort and expense. (I wish the movie didn’t feel the need to apologize and explain—sadly, it knows it does.) The clunkiness of the connecting scenes keeps the film from truly getting underway—it moves like a jeep on a dirt road—although a couple of well-written conversations keep the interest going. One involves Stokes, a pack of cigarettes, and a Nazi POW; the other has Damon’s art restorer passing an evening in Paris with his contact, a museum employee (Cate Blanchett) who watched the Germans move hundreds of artworks out of the city under her careful, wary gaze. (Her character is based on one of the most amazing true stories to come out of the Monuments Men effort.) For a moment, Damon and Blanchett get a palpably human connection going amid the historical do-goodery. There’s a movie that might be made from that moment, but The Monuments Men is too dutiful for that. Robert Horton

PThe Past

Opens Fri., Feb. 7 at Guild 45th. Rated PG-13. 130 minutes.

More than one separation is at the heart of The Past, Asghar Farhadi’s first film made outside his native Iran. In a country where cinematic talent exists in inverse proportion to artistic freedom, Farhadi emerged as a major figure when his fifth feature, A Separation, wowed festival audiences and eventually won the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar last year. Although the Iranian powers-that-be tend to convey ambivalence about their filmmakers’ success overseas (do we take a moment for nationalistic chest-thumping, or condemn the Western devils and their corrupting influence?), something about A Separation earned Farhadi the right to journey to France to make his next picture.

With one exception, The Past is much like A Separation: deliberate, full of feeling, scrupulously made. It begins after a four-year separation. Ahmad (Ali Mosaffa) has come from Iran to Paris to finalize his divorce from Marie (saucer-eyed Berenice Bejo, from The Artist), who is anxious to get on with her life with new beau Samir (Tahar Rahim, A Prophet). At least she seems anxious, although she keeps finding reasons for Ahmad to stay around her house. But the situation is much more complicated than that. Part of the drama revolves around Marie’s teenage daughter from a previous relationship, Lucie (Pauline Burlet), who still needs Ahmad’s fatherly advice after having carried around a guilty secret for a long time. This secret provides the film with its plottiest device, a melodramatic thread that keeps The Past from reaching the delicate achievement of A Separation. It’s like a 45-minute whodunit that suddenly sprouts inside a character study.

Still, the movie shows a deep empathy for its people and a strong sense of place—not a sense of France, perhaps, but a feeling for a humble neighborhood (this is not romantic Paris), the surrounding streets, a workaday dry-cleaning shop. We could be almost anywhere. It builds to a sequence in a similarly humble hospital, where one storyline in this drama has been dragging on for months. The sequence lasts a few minutes but consists of a single shot, an approach that allows Farhadi to convey the importance of time (the film is called The Past for a reason) as both torture and consolation. The longer the shot goes on, the closer we watch for the tiny clues that will indicate how a number of lives will be affected by what happens here. And if we’re paying close-enough attention, we’ll see something that rounds off this sad film with a fitting farewell. Robert Horton

Visitors

Opens Fri., Feb. 7 at Cinerama. Not rated. 87 minutes.

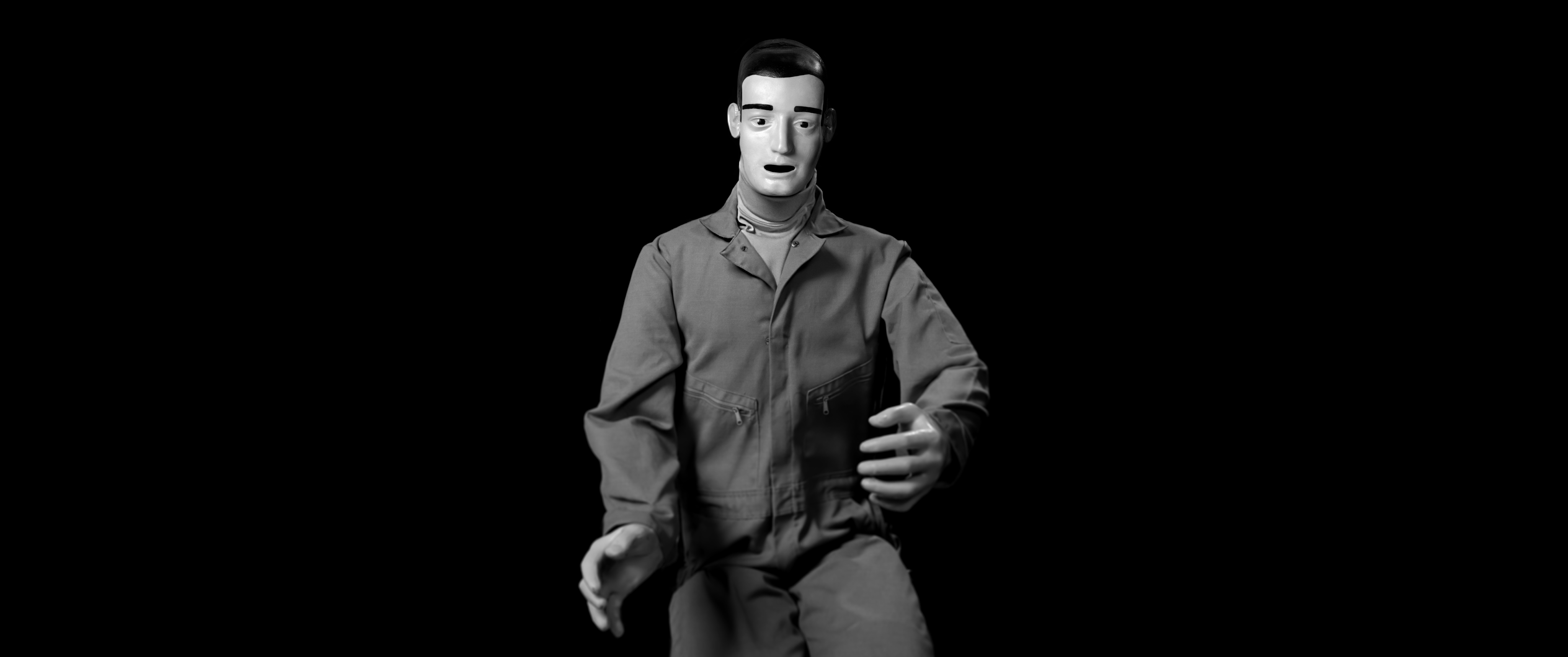

Shot in super-high-def black-and-white digital video, this is the latest state-of-the world doc from Godfrey Reggio (Koyaanisqatsi, etc.), and he doesn’t like what he’s seeing. He also doesn’t like how we’re seeing the world, which increasingly means small, flat screens held in our hands and laps. Where’s the grandeur, the awe, the majesty? Has all the numinous wonder of nature been replaced by Facebook and Twitter? And another thing—you damn kids get off my lawn!

You would call Visitors a film of ideas if it had any. Absent any narration, as usual for Reggio, the film presents a succession of somber images that eventually settles into cliche: a gorilla’s face, an abandoned amusement park, a giant hand manipulating a computer mouse, sports fans watching a game in slo-mo, a mangrove swamp, an albino posed between two black people (yes, really), the lunar surface, a New Orleans cemetery, and so on. (Also s usual for Reggio, Philip Glass supplies the score.) But how many times must we watch time-lapse shadows crawl across a building’s facade? (That edifice’s Latin inscription, Novus Ordo Seclorum, translates as “new order of the ages”—which you’ll also find on the dollar bill, beneath the all-seeing Illuminati pyramid eye. Make of that what you will.) We study the faces of mankind individually, like Martin Schoeller portraits, then in teeming crowds. It’s like scrutinizing strangers on the bus. To fight boredom, you keep hoping you’ll recognize someone you know.

Visitors moves in a structure along with Glass’ three symphonic movements, and I prefer the music. The score is often Coplandesque in its thrumming harmonies, full of woodwind drones and plangent timpani clusters; oboes erupt in unison, interrupted by pizzicato strings. In a film that’s intentionally repetitious, full of echt profundity and audience implication, Glass at least escapes Reggio’s banal image sequencing. If Visitors argues for a more authentic, unmediated way of seeing the world, the music allows us to imagine an unseen world. Close your eyes, and it’s like Reggio forgot to take off the lens cap. Brian Miller

Walking the Camino:

Six Ways to Santiago

Runs Fri., Feb. 7–Thurs., Feb. 13 at SIFF Cinema Uptown and SIFF Film Center. Not rated. 84 minutes.

Martin Sheen has already starred in a gentle comedy about pilgrimage paths in Northern Spain (2010’s The Way, directed by his son Emilio Estevez), so this new doc feels slightly out of sequence. Usually it’s the other way around: first the sober nonfiction chronicle, then the cutesy Hollywood version. And if anything, in its international, uplifting cutesiness, Lydia Smith’s film may actually be more genial than its predecessor. A few priests explain the history of the pilgrimage paths to Santiago, where St. James is supposedly buried. At 500 miles from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in southwestern France, the Camino is a strenuous walk on both paved roads and pastoral trails, a trek that takes a month for most walkers. (A series of hostels en route provides bunks and grub.)

Not all of these half-dozen trekkers are strictly religious. For one young Portuguese businessman, the Camino is a personal challenge. A cheerful, sturdy Danish woman wants the time alone—then falls in step with a handsome Canadian. Annie, the lone American, is a New Agey but engagingly candid woman of a certain age; she says nothing about her life back home, but you suspect that her kids are in college and she’s possibly divorced. Then there’s the British-accented Samantha, a brash Brazilian who says she’s lost her job, boyfriend, and apartment back in London. She stops for regular smoking breaks, flirts shamelessly, and would be a far better heroine than Julia Roberts in the Eat Pray Love/Under the Tuscan Sun memoir category.

This cheerful travelogue could well have been produced by the Spanish National Tourist Board. I’m not saying it’s an informercial, but the fellowship among these travelers is enormously appealing. The scenery is gorgeous and often medieval, so much so that you can forgive the platitudes—“Every day is a journey,” “The baggage you carry is your fears,” etc. A better summation comes from a Canadian cleric, who simply calls their 30-day journey “a luxury of time.” Brian Miller

E

film@seattleweekly.com