Opening ThisWeek

PGone Girl

Opens Fri., Oct. 3 at Sundance, SIFF Cinema Uptown, and other theaters. Rated R. 145 minutes.

Likable characters are a curse in Hollywood. Studios want someone relatable, someone personable, someone who looks friendly on the cover of Us magazine. What the movies emphatically don’t like is a dour mug like Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) staring at them on a tabloid TV show: five o’clock shadow, dimple, a drinker’s saggy eyes, unsmiling and seemingly unloving about his missing (and presumed murdered) wife Amy (Rosamund Pike). What’s exceptional about Gillian Flynn’s adaptation of her 2012 novel, directed with acid fidelity by David Fincher, is that Gone Girl doesn’t like most of its characters either. Those who aren’t sociopaths are numbskulls or clowns. Ozark hillbillies and TV hucksters stroll through the action, along with nitwit trust-funders and desperate housewives.

What’s to like? Who’s to like? And where to start with a movie brimming with plot twists and sudden reversals of perspective? For those like me who didn’t read Flynn’s bestseller, I’ll say that the small-town Missouri police investigation (led by Kim Dickens, from Treme and Sons of Anarchy) goes entirely against Nick for the first hour. He behaves like an oaf and does most everything to make himself the prime suspect, despite wise counsel from his sister (Carrie Coon) and lawyer (a surprisingly effective, enjoyable Tyler Perry).

Second hour, still no body, but flashbacks turn us against the absent Amy. (Here the English Pike, of the current Hector and the Search for Happiness, gets to try on a New Orleans accent and embrace her inner trailer-park diva.) Fincher takes his time with the story—probably too much time for those expecting a straightforward thriller. He’s a famous crime-procedural perfectionist (e.g. Seven and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo) not much known for a sense of humor, so the perverse levity I’ll attribute to Flynn. As we slowly investigate the Dunnes’ very flawed marriage, funny little kernels of bile begin to explode underfoot. Control-freak Amy, as it turns out, was precisely plotting against Nick with colored Post-It Notes. And Nick, when red panties are found in his college office, can’t be sure if they were left by his wife or an amorous student. How the hell did these two end up together?

Flynn’s foundational joke answers that question with a satire of marriage. The movie poster and tabloid-TV plot suggest a standard I-didn’t-kill-my-wife tale, but matrimony is what’s being murdered here. Role playing and mundane daily deceptions— “No, honey, your breath doesn’t stink in the morning”—are integral to the daily maintenance of the nest. Then, scrutinized by the media circus, all those necessary little lies begin to look pathological. Nick becomes the scorned sap because of his untruths; but what really damns him in the movie’s intricate plot is his credulity—he believed in Amy too much. And here let’s add that Flynn has clearly studied the dark, twisty movies in which Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray used to star in the ’40s. Shades of Laura hang over Amy’s ghostly televised image, too.

Gone Girl is all about manipulation—Fincher’s stock in trade, really, which helps make the film such cynical, mean-spirited fun. It’s not Coen Brothers-funny, but black humor helps mitigate the late-film geyser of blood. (There’s only one body in the film, and not the one you expect.) In a key, creepy role, Neil Patrick Harris gets to coin a new catchphrase with “Octopus and Scrabble!” And Flynn lets Nick and Amy supply the movie’s motto: “All we do is cause each other pain.” “That’s marriage.” Brian Miller

Kelly & Cal

Opens Fri., Oct. 3 at SIFF Film Center. Not rated. 109 minutes.

Kelly is a onetime ’90s riot grrrl, now a domesticated new mom and prisoner of suburbia. Who better to play the part than Juliette Lewis, a survivor of such wild-child projects as Natural Born Killers and Strange Days and a veteran musician known for her theatrical caterwauling? Lewis lends lived-in credibility to the otherwise bogus Kelly & Cal, a stilted indie without a compass. Kelly is new to the neighborhood, shunned by the local ladies (they suggest she consult their website if she’d like to join their social group), and ignored by husband Josh (Josh Hopkins), who’s at the office all day. And so she starts hanging out with local teen Cal (Jonny Weston, from Chasing Mavericks), a paraplegic who makes it clear he’s interested in Kelly’s body as well as her sassy punk-rock attitude.

A series of contrivances allows the plot to unfold: Josh’s mother (Cybill Shepherd, spacey as ever) and sister (Lucy Owen) insist on tending the new baby in the afternoons—they consider Kelly’s blue hair dye a sign of post-partum mental illness—thus making plenty of free time for Kelly to lounge around in Cal’s garage. Even if you’re with the movie thus far and sympathetic to the trapped feelings of the title characters, there’s a moment when director Jen McGowan and screenwriter Amy Lowe Starbin fumble it all away: Kelly plays a cassette from her music days for Cal, and the song—“Moist Towelette”—rings out. I couldn’t tell whether the movie wants us to take this straight or as a parody of a riot-grrrl anthem; either way, it makes Kelly look idiotic (the sound is good, but the lyrics are impossible). In fact, “Moist Towelette” and an end-credits tune called “Change” were written and performed by Lewis in the mode of something her character might create.

The film becomes increasingly unbelievable, but the most annoying thing about it is the failure to commit. Kelly & Cal doesn’t have the nerve to go all the way with its more troubling implications, so it stays on the surface throughout. In the movie universe, there must be a place for the curious lost-girl presence of someone like Juliette Lewis, but if this film gets the casting right, it blows the execution. Robert Horton

PLast Days in Vietnam

Opens Fri., Oct. 3 at Varsity. Not rated. 98 minutes.

How, short of total victory, do you end a war? The question has been haunting our military and political leaders since Korea. And though Rory Kennedy’s sobering new doc focuses on the last few desperate days of the Vietnam War, 40 years ago, its lessons are surely applicable today in Iraq, Afghanistan, and whatever the hell it is we call ISIS.

Kennedy, director of Last Days of Abu Ghraib and daughter of RFK, is obviously super-connected. She gets Kissinger on camera, plus other veterans of Nixon’s White House, but the bulk of the testimony here comes from guys who were actually on the ground in Saigon—soldiers (American and Vietnamese), a CIA agent, embassy staffers, and the stray journalist or two. These fresh interviews are coupled with vivid archival news footage from a time when photojournalists were on the frontlines. They filmed on both sides of the U.S. embassy walls as a terrified tidal wave of humanity sought evacuation before the North Vietnamese Army overran Saigon in late April 1975. Kennedy’s task is now to make sense of that chaos.

Direct U.S. involvement in the war had concluded with the 1973 peace accords; but, as in Baghdad today, a sizable American contingent remained. Then Nixon resigned after Watergate, and North Vietnamese fears of new carpet bombing were dispelled. President Ford couldn’t get any military-assistance funds out of Congress (no surprise), and the NVA began its swift, relentless drive south. With a deluded ambassador in charge, his men began a covert evacuation plan that would also include thousands of Vietnamese (despite orders and U.S. immigration laws): girlfriends, wives and families, friends, and brothers-in-arms. (“We gotta save the tailor!” says one attache whose suits he made.)

There’s intrigue in these brave tales that occasionally recalls Argo, only with an unhappy outcome for all those natives left behind (some of whom Kennedy interviews). The helicopters frantically shuttled thousands to U.S. ships, and one Navy commander says the accompanying boatlift “looked like something out of Exodus.” Does he mean the Bible, the Leon Uris novel, or the movie? The analogy works in all senses. Events here took place only three decades after the Holocaust and the postwar partition of Europe. How could we Americans not feel guilty about our past failures? Starting with the best intentions, our country became the retreating imperial arbiter between the drowned and the saved. Kennedy hardly has to say it, but the same unhappy situation exists today. Brian Miller

The Liberator

Opens Fri., Oct. 3 at Sundance Cinemas. Rated R. 118 minutes.

The Great Man school of biography is alive—if not particularly well—in The Liberator. A quick glimpse of unloving parents, a tragic lost love, reluctant heroism, sweeping battle scenes, and of course a charismatic international star: All are part of the once-over-lightly treatment. The great man in question is Simon Bolivar (1783–1830), the George Washington of South America; the star is Edgar Ramirez, whose dashing performance as the Jackal in the three-part Carlos bagged him roles in Hollywood projects like Clash of the Titans and Deliver Us From Evil. Because the Venezuelan-born Bolivar’s goal was nothing less than the liberation of an entire continent from colonial rule, there’s a lot to cram into a two-hour movie. This means historical complexity is sidelined in favor of scenes in which Bolivar is nobly seated on the back of a charging horse, or clutched in the embrace of a beautiful woman while assassins lurk outside the hacienda. The images are handsome, but they don’t make much sense.

The movie looks as though it has a budget, so the battle scenes are credible enough. Beyond the appeal of the physical production, director Alberto Arvelo goes for the well-worn anecdote—the equivalent of Washington’s cherry tree or Lincoln’s rail-splitting. A sequence in which Bolivar thrashes the native boy who steals his boots, then reconsiders his privileged reaction, is offered as a classic turning-point parable. This approach leaves aside much of the complicated business of geopolitics, although the recurring figure of an English banker (Danny Huston) stands in for all the outsiders waiting to profit from whatever happens after the revolution. Screenwriter Timothy J. Sexton provides enough scenes of Bolivar delivering speeches to guarantee some rousing rhetoric, and the movie does stir to life whenever an all-or-nothing battle looms. (The musical score is by wonder-boy L.A. Philharmonic conductor Gustavo Dudamel.)

The brawny Ramirez handles both speechifying and swordplay with aplomb, and he suggests just enough of Bolivar’s aristocratic blood to keep the character from becoming saintly—Ramirez always looks as though he might be tempted back into lying in a hammock and eating peeled grapes. That’s not enough to save the movie, which never rises above the level of a dutiful classroom essay. Robert Horton

Pacific Aggression

Runs Fri., Oct. 3–Thurs., Oct. 9 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 100 minutes.

Local filmmaker Shaun Scott’s history-infused love story is superficially a case of opposites attracting. Native American college student Meryl (Libby Matthews) is cyber-stalking New York author Frank (Trevor Young Marston), whom she met on a book tour two years before. She embraces the Web and social media—so much so that she’s undergoing a “digital cleanse” with her shrink (Marya Sea Kaminski). Frank, though he’s blocked on his next book project, meanwhile disdains the Internet—until his editor convinces him it’s the best way to promote his new travelogue. This, conveniently, takes him back to Seattle, where Meryl is waiting, though Pacific Aggression bides its time in reuniting the pair.

First, Scott wants to educate the viewer about the history of Washington state and the West in general. He makes Frank a history buff, fond of watching old cowboy movies in motel rooms. Frank’s ruminations on the frontier, like Meryl’s explication of her heritage, are illustrated via eclectic old archival footage. Scott has employed this hybrid approach before in his 100% Off: A Recession-Era Romance, couching a fictional tale in its socioeconomic context. This makes Pacific Aggression as much a lesson, often talky, as a romance—which is equally talky. Frank and Meryl are staunch literary types, and their constant musings give the movie an epistolary feel. Around them, a few supporting characters also add to the swirling debate. (You’d like to see more of Kaminski, a noted local stage actress, who performs a silent meltdown while listening to the car radio.)

Just as one expects Frank and Meryl to eventually connect, one hopes all these discursive lines will eventually land on a solid thesis. Pacific Aggression is nothing if not ambitious by local film standards, with interests that extend to uranium mining near Spokane and the A-bomb dropped on Hiroshima. That’s a lot for Scott, let alone his characters, to chew; and the easy part is simply to supply his lovers with a happy ending. The greater challenge, where this smartly engaged movie falls a little short, is to reconcile the broader underlying conflicts behind the love story. And yet, how many couples ever put past differences behind them? Brian Miller

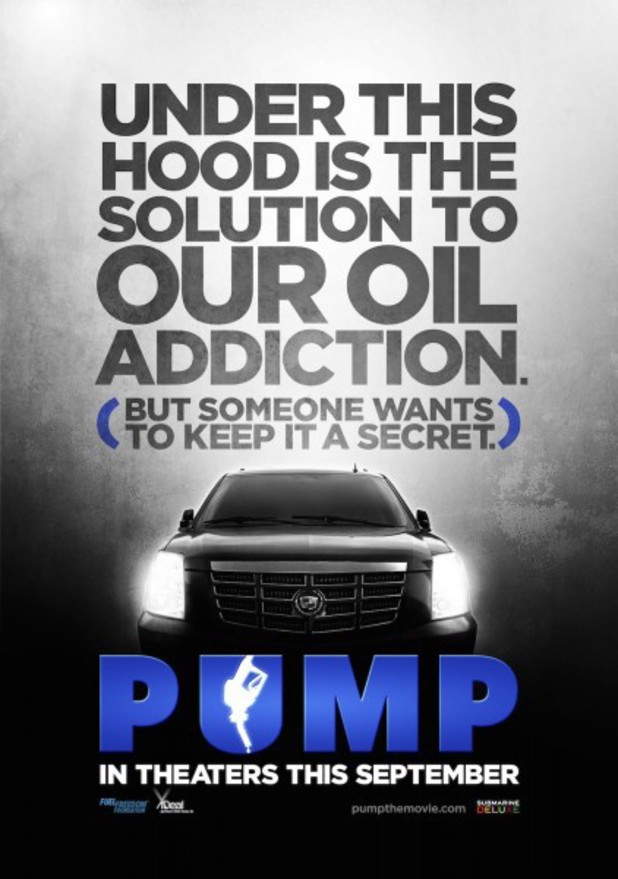

Pump

Opens Fri., Oct. 3 at Sundance. Not rated. 88 minutes.

This new advocacy doc is essentially the bastard child of Who Killed the Electric Car? and Fuel (also directed by Joshua Tickell). If you’re in the market for a Nissan Leaf, if you’re eager to run your present car on biodiesel or other alternative fuel, if you’re keen on conspiracy theories, this movie is for you. Did you know that Prohibition was a gambit by Standard Oil baron John D. Rockefeller to prevent Henry Ford from allowing his cars to run on ethanol? In this version of history, uncorroborated by actual historians, the temperance movement never existed. Certainly Big Oil has had undue influence in Washington, D.C., but is that the only reason for the petro-monopoly of the marketplace? The film’s producers, affiliated with the Fuel Freedom Foundation, allow no such quibbles or nuance.

Relentlessly optimistic and one-sided (even for those who may agree with that side), Pump is too much the infomercial, with plugs for Elon Musk and Tesla, biofuel peddlers, and various hackers selling semi-legal fuel conversion kits. It takes 40 minutes of historical recap—Rockefeller, Ford, Nikola Tesla, OPEC, the Gulf Wars—to get to the film’s belabored thesis, which boils down to the cheerful twin mantras of empowerment and choice.

Yes, electric cars—mostly powered by coal, let’s note—and flex-fuel vehicles are a good thing, but is Brazil, with its government-mandated sugar-cane fuel industry, really the right economic model for the U.S.? Pump insists so. So fixated is the film on the original sin of oil that it never for a moment addresses sprawl or mass transit. If you gave every Seattle-bound commuter a free Tesla, the city would become a giant, emission-free parking lot. Is oil the problem here or single-car driving from the suburbs? Pump makes no such distinctions.

Jason Bateman narrates, though there is no mention of transportation alternatives like carpooling, the stair car, or hop-ons. Brian Miller

PTracks

Opens Fri., Oct. 3 at Sundance. Rated PG-13. 102 minutes.

Mia Wasikowska’s face, body language, and vocal delivery are in perfect harmony with the countryside that surrounds her in Tracks: human figure and landscape are equally mysterious and unforgiving. The place is the Australian desert, where in 1975 a young woman named Robyn Davidson determined she would walk the 1,700 miles from Alice Springs to the Indian Ocean. In writing a National Geographic article and subsequent best-selling book about the trek, Davidson offered little explanation for her impulse, and the movie is blunt about acknowledging that no coherent justification can be made on that score. She just needed to do it. Wasikowska’s skeptical gaze and stony delivery are ideal for this tough character, and the actress never makes a bid for likability. We observe Davidson as she puts in months of camel training—she’ll need them to carry her stuff for the trip—even before she actually leaves Alice Springs. Once on the path, she endures/exploits the expectations of National Geographic photographer Rick (Adam Driver, from Girls—a necessary warm presence in this severe portrait), as he periodically meets her along the long miles of desert scrub. She also has her dog, Diggity, who remains spirit animal and soulmate for the trip; the only other fellow trekker is Mr. Eddy (Rolley Mintuma), a garrulous if largely unintelligible aboriginal guide who helps Davidson tread respectfully around sacred sites for a few weeks. Beyond that, it’s sand and sun and willpower.

Director John Curran (The Painted Veil) imagines this journey in an admirably terse way. We do hear Davidson’s words on the soundtrack, but for the most part the movie simply forges ahead; the romance-of-the-desert familiar from Lawrence of Arabia is kept at bay. This isn’t about conquering the land, but it’s not a reassuring journey of self-discovery, either—Davidson seems a little too close to yearning for oblivion for this to be about empowerment. If you’re getting the idea Tracks isn’t exactly cuddly, that’s true; it’s easier to get excited by something like Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout (1971), a more lurid take on outback trekking, made just before Davidson took her real walkabout. But Tracks feels true in spirit to the kind of soul who really would take this journey, which explains why you’re right there with this solitary woman every step of the way. Robert Horton

E

film@seattleweekly.com