Opening ThisWeek

PBastards

Runs Fri., Nov. 15–Thurs., Nov. 21 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 83 minutes.

If Alfred Hitchcock were still alive and exploring 21st-century modes of moviemaking, would he come up with something like Bastards? The Master of Suspense changed with the times, and maybe it’s not too far-fetched to imagine him experimenting in the style operating here: a terse, elliptical, and ultimately horrifying method that withholds as much information as it doles out.

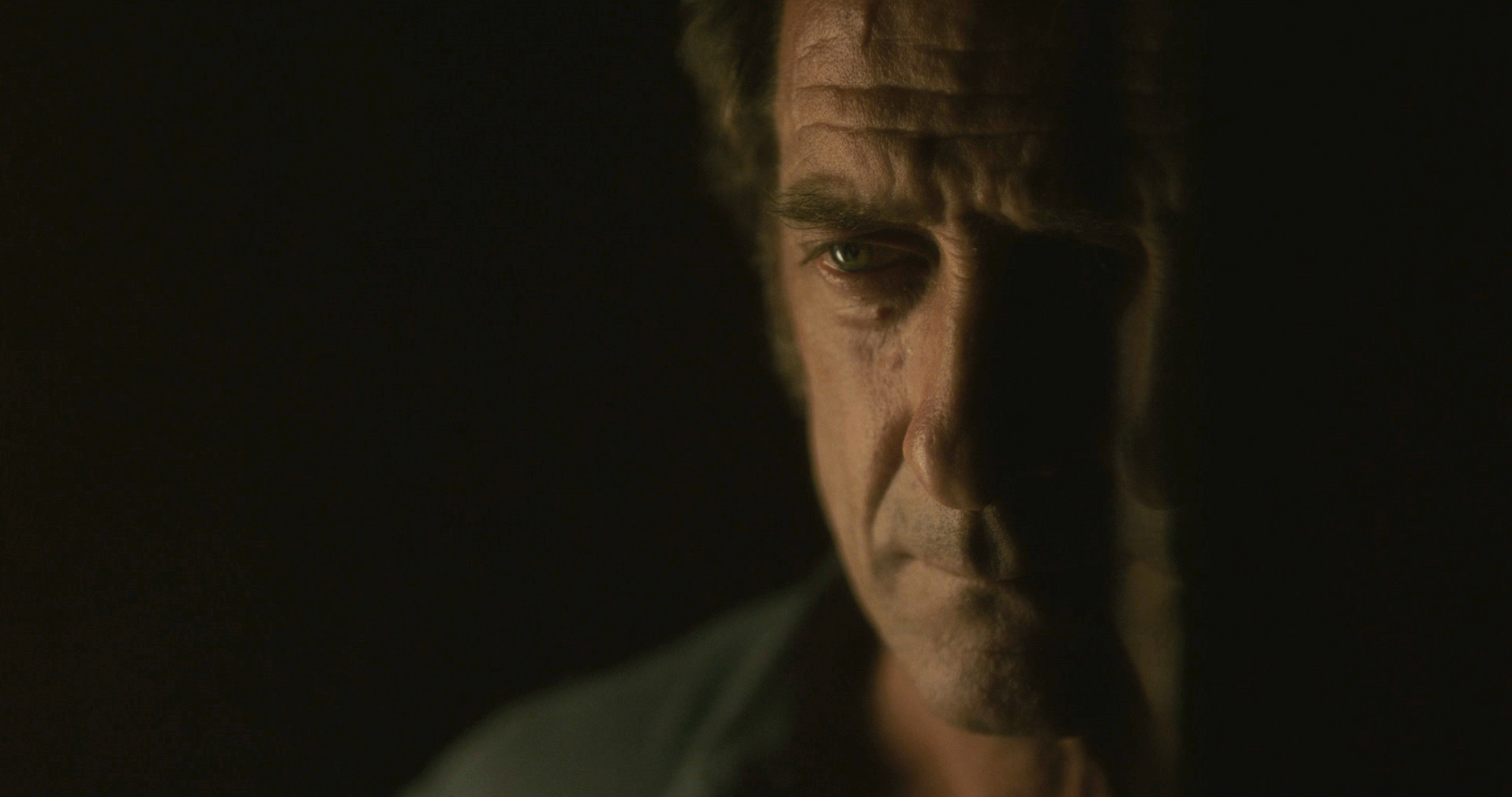

This thought passed through my mind halfway through Bastards, but make no mistake: This movie is definitely the work of French filmmaker Claire Denis (White Material, 35 Shots of Rum, Beau Travail, etc.), whose cryptic approach only adds to the film’s creeping sense of unease. The picture begins by contemplating a wall of rain, as though preparing us for how hard it will be to see and understand what’s going on. A man commits suicide on this rainy night, and his brother-in-law Marco (Vincent Lindon) quits his job as a ship’s captain in order to come home and sort things out for his deeply damaged sister (Julie Bataille) and niece (Lola Creton). Marco moves into a huge, empty apartment across the hall from a prominent businessman (Michel Subor), who lives with trophy mistress Raphaelle (Chiara Mastroianni) and their young son. The hints that emerge about this world grow darker as the movie goes on—and are, in fact, about as dark as a family nightmare can get.

With his blunt masculinity, Lindon raises our hopes that his rugged loner can rescue the disaster. That’s what rugged loners do in movies. But Denis is aware of how the power stacks up in this situation, so the resolution is probably going to be closer to Vertigo than Rear Window. And for a movie obsessed with how difficult it is to see the truth (and how reluctant people are to acknowledge it), it is fitting that surveillance cameras and other recording devices are an almost-unnoticed fact of life—culminating in the last, terrible sequence. A final piece of evidence, knowingly recorded for a camera, confirms our worst fears. Bastards is a skillfully assembled mosaic, the work of a filmmaker fully in control of her talents; and despite the grim material, we can at least find some satisfaction in how well the tale has been told. But Claire Denis sure doesn’t make it easy on us. Robert Horton

Charlie Countryman

Opens Fri., Nov. 15 at SouthCenter. Rated R. 108 minutes.

Because of those Transformers movies, Shia LaBeouf gets the rap as a no-talent young journeyman who won the casting lottery. (Being fired by Daniel Sullivan, formerly of Seattle Rep, from this year’s Broadway revival of Orphans didn’t help his reputation.) But when not running from giant robots, LaBeouf hasn’t been terrible in The Company You Keep (as a reporter one step behind his story) or Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (as a financier one step behind Michael Douglas). He never seems to be in command of a movie, even when he lands the starring role. Yet there’s something authentically fugitive and rabbity about the guy, as though he never stops long enough to think anything through. You can’t really imagine him playing a master spy or genius hacker; and it may take another decade to see if he pulls a McConaughey and develops any depth as an actor.

For that reason, LaBeouf works just fine as a scared young Chicago tourist who stumbles into Bucharest’s underworld of gangsters and classical musicians. Innocent, bewildered Charlie knows nothing about handguns or Handel; he just runs through the city with goons and cops on his trail, receives multiple beatings, and falls in love with a lovely young cellist (Evan Rachel Wood). Oh, and one more thing: Charlie sees dead people. There’s even a Sixth Sense joke in Charlie Countryman, which is a little more meta than needed. Charlie communes with the spirits of his kindly mom (Melissa Leo) and the cellist’s wise father (Ion Caramitru). Yet these ghostly interludes are mostly lighthearted—nothing so leaden as M. Night Shyamalan. Effectively shot on location in Romania, Charlie Countryman is fundamentally a chase movie, with Mads Mikkelsen and Til Schweiger the baddies in pursuit of LaBeouf. His Charlie is certainly part of the action, only somehow always one step behind. Brian Miller

PGod Loves Uganda

Runs Fri., Nov. 15–Thurs., Nov. 21 at SIFF Film Center. Not rated. 83 minutes.

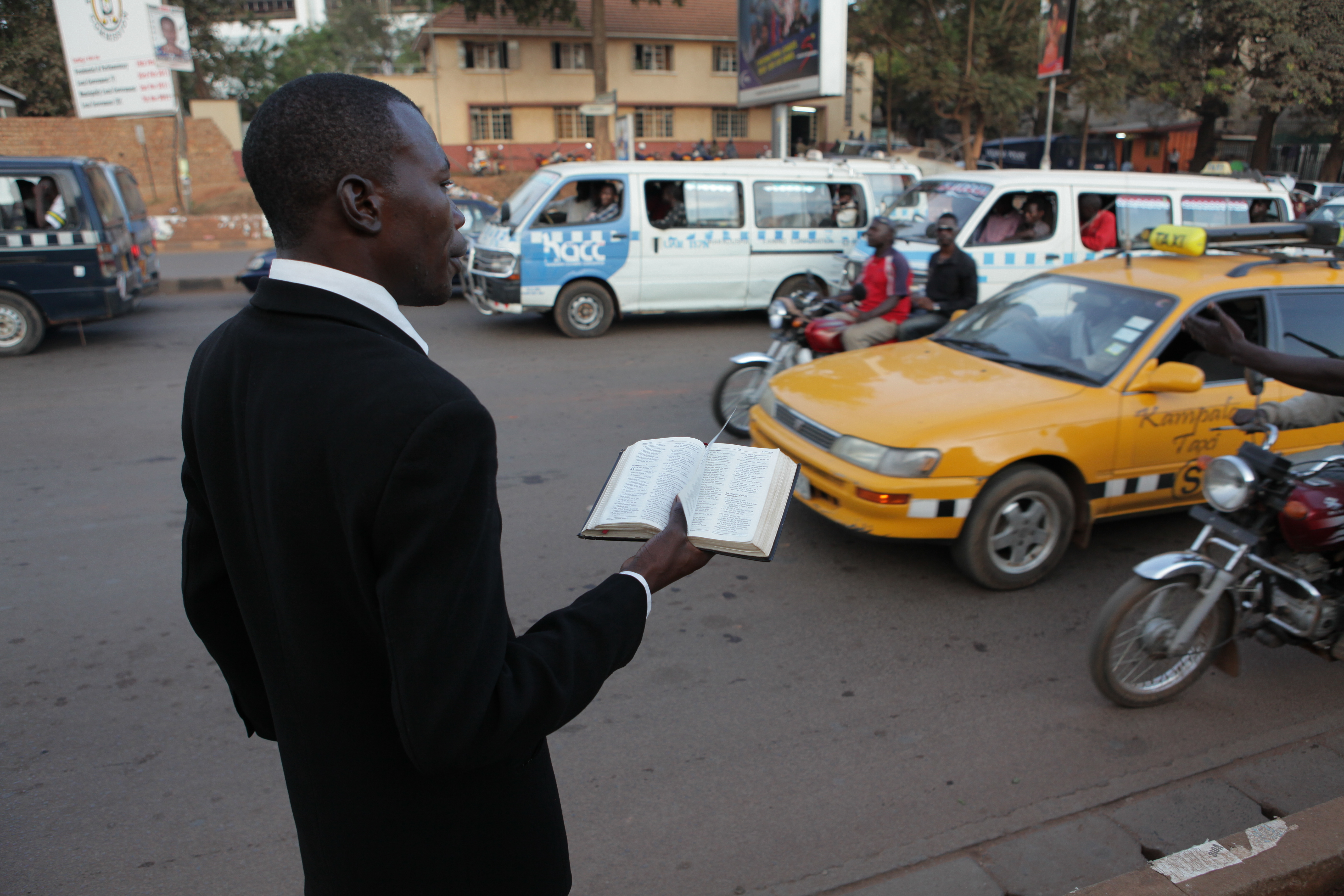

If he’d wanted to go the first-person Michael Moore route, Roger Ross Williams could have gotten some high drama into this documentary. Williams told The Hollywood Reporter that after shooting in Uganda for a few weeks, he was taken aside by a group of bishops who had discovered his sexual orientation. Homosexuality is illegal in that nation, and these clerics had been preaching their vehemently antigay beliefs to him, so the moment was tense. Williams was lucky; the priests began praying over him, the better to cure him.

That moment is not included or described in God Loves Uganda, nor is Williams a presence in the movie (there is no narration). Instead, what he presents is a lucid and appalling portrait of the modern missionary movement and the effect it has had on a single African nation. Although Uganda’s widely criticized (and still pending) legislation threatening the death penalty for homosexual behavior is described in the movie, the broader subject here is the way American evangelicals are pouring money and legwork into the country. Williams tags along with missionaries from a Kansas City megachurch known as The International House of Prayer (yes, they call themselves IHOP) who pour their spiritual syrup over the burgeoning phenomenon of Christian fundamentalism in Uganda. That movement’s leaders, American and Ugandan alike, share a particular enthusiasm for denouncing homosexuality, which the movie connects to the rise in antigay sentiment in the country. The most humane exception is Bishop Christopher Senyonjo, whose sympathy with the LGBT community has made him controversial in Uganda. We also meet Kapya Kaoma, an Anglican priest who particularly notes how much harder it’s been to fight the AIDS epidemic since the instigation of “abstinence-only” policies encouraged by religious groups.

Williams, who won an Oscar for the 2010 short film Music by Prudence, generally plays fair with his material. No editorial comment is needed when you have a shot of true believers wandering through a large room, apparently speaking in tongues; it might have come from a sci-fi picture. Showing what’s going on is enough. In a dismal village, a fresh-faced American woman discusses eternity with an older Ugandan lady. “If you die today and have not repented,” she reports, “you will not be with us in paradise. Does that scare you?” There are plenty of frights to go around in God Loves Uganda. Robert Horton

PI Am Divine

Runs Fri., Nov. 15–Thurs., Nov. 21 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 90 minutes.

Harris Glenn Milstead, aka the drag queen Divine, died 25 years ago at the peak of his career, untouched by AIDS, perhaps the most unlikely movie star in alternative-become-Hollywood screen history. Jeffrey Schwarz’s fond tribute documentary is rooted in Baltimore and the recollections of John Waters, Divine’s benevolent Svengali. (There were other formative mentors, we learn, but most are dead.) It may be hard to recall now, after Hairspray has been adapted into a popular stage show and movie musical (cue John Travolta) and with Drag Race a mainstream TV staple, what a disruptive force Divine once was. He went beyond “passing” or prettiness or burlesque into a nether realm of exaggerated, messy revenge—“to use that anger from all his high-school traumas,” says Waters. In a way, Divine’s triumphant story is Revenge of the Nerds before nerds, sadistic glee before Glee. Before the 1988 Hairspray and his death that year, he told Charlie Rose “Cult status isn’t enough.” He wanted more praise from Pauline Kael. He wanted to be a real character actor, like Charles Laughton, who transcended drag.

Sadly, he hardly got the chance. (One notable exception: Alan Rudolph’s 1987 Trouble in Mind, shot here in Seattle.) Divine died in his sleep soon after winning a recurring non-drag role on Married With Children (his episodes were never filmed). As a result, most of the clips come from Waters’ shock perennials, like Polyester, Pink Flamingos (with the notorious dog-poo-eating scene), and Female Trouble (also being screened at 10 p.m. Friday and Saturday). There are also generous selections from Waters’ home-movie collection and that of Divine’s family, from whom he was long estranged before a happy reunion. Praise rolls in from co-stars Mink Stole, Tab Hunter, and Ricki Lake and writers including The

Village Voice’s Michael Musto. Milstead clearly had his demons—food chief among them—but also seemingly enjoyed near-total admiration from those in showbiz. He was a big stoner, says Waters, which might explain his mellow offstage demeanor, so different from the shrieking live shows we see. And did you remember that Divine cut a series of late-disco albums during the ’80s? Those music videos are a treat to behold.

Yet inescapably, Divine is now part of boomer nostalgia, like midnight movies, gay cabarets, and Studio 54 (where he met Andy Warhol, the Rolling Stones, and most of his idols). What was outrageous then almost seems quaint to us now. Time and distance have granted Divine a halo, and he wears it well. Brian Miller

In the Name Of

Runs Fri., Nov. 15–Thurs., Nov. 21 at Sundance. Not rated. 102 minutes.

You may recall the controversy, some 20 years ago, surrounding the English film Priest, about a Catholic cleric hiding his homosexuality. A lot has changed since then. Still, after so many pedophilia lawsuits and exposes (including the 2006 documentary Deliver Us From Evil), this Polish drama might seem redundant—or worse, sensationalist. So we have a handsome parish priest, transferred from Warsaw to a rural village, where he oversees a reform-school farm full of shirtless, horny teens. Father Adam (Andrzej Chyra) came late to God, he explains in a sun-washed sermon, though he’s vague about his past. When not working (generally out of his cassock), he exhausts himself by running through the forest to deplete his desire. After rebuffing the wife of a colleague, he makes tearful, drunken Skype confessions to his unsympathetic sister in Toronto. He is, profoundly and sadly, alone.

A rough-trade, bottle-blond teen arrives at the farm, and Adam watches aghast—or enviously—as he cornholes another lad on the rectory couch. (That defiled furniture is promptly removed.) But lurking around the periphery is gentle, long-haired farmhand Lukasz (Mateusz Kościukiewicz), nicknamed “Humpty,” who silently falls in love with the kind Adam. How can this situation be tolerated? Why doesn’t Adam simply leave the church and take Lukasz back to the more-tolerant city?

The weight of tradition and the rhythms of rural life are keenly felt in Małgośka Szumowska’s very assured drama, handsomely shot in widescreen. (Her Elles, with Juliette Binoche as a journalist studying hookers, played the Varsity last year.) Lukasz is loyal to his family because they’re poor, and Adam is loyal to his flock because they plainly need him. In the Name Of isn’t so much about sexual frustration or religious hypocrisy as the conservative bonds of Catholic Poland. Lukasz and the reform-school boys were born after communism, but Adam and his church are still ruled by an inflexible hierarchy. (“We don’t sweep dirt under the carpet,” says a bishop, who does just that.) A different film might explode into conflict or reward us with a happy ending. Instead, in a very deliberate fashion, Szumowska suggests how a cycle of secrecy is perpetuated beneath the collar. Brian Miller

Kill Your Darlings

Opens Fri., Nov. 15 at Meridian, Sundance, and Lincoln Square. Rated R. 100 minutes.

The Beat generation grew up on movies (and jazz and jukeboxes and Rimbaud), but it hasn’t been well served by the movies. Howl, On the Road, and Big Sur are among recent efforts to capture that boundary-breaking time; Kill Your Darlings is earlier and much more specific, tackling one crime and a few months on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where a naive freshman arrives at Columbia University in 1944. His name? Allen Ginsberg, the shy son of a New Jersey poet and a mad housewife. That Daniel Radcliffe plays the young Ginsberg means people will take notice of this film. (Meanwhile, his Harry Potter colleague Rupert Grint provides minor comic relief in Charlie Countryman, also out this week.) Radcliffe has been on a tear since Deathly Hallows, working hard and often to prove he’s got a future outside Hogwarts.

He does, and there’s much to commend about how he turns a watchful virgin into a shrewd campus survivor. I just wish the story—by Austin Bunn and first-time director John Krokidas—better served his talents. Ginsberg is initially awed by fellow student Lucien Carr (DiCaprio DNA culture Dane DeHaan), a privileged, blond, romantic WASP so unlike himself. Carr has other male admirers, including William S. Burroughs (Ben Foster, perfect), David Kammerer (Michael C. Hall), and—in a less sexual way—Jack Kerouac (Jack Huston). Students of Beat literature know how and why all these famous names actually converged; for younger readers, let’s just say that a killing links them.

Nothing dates faster than your father’s bohemia. The filmmakers do everything possible to make a 70-year-old murder mystery seem fresh. Kill Your Darlings is aggressively overscored with anachronistic tunes, overedited to match the amphetamines, and overserious about these poets’ grand sense of themselves. This self-declared “Libertine Circle” tears through the Village and Harlem, their strenuous jollity and campus hijinks supposedly corresponding to the coming literary revolution. (Howl and On the Road would be published in 1955 and ’57, respectively.) But sometimes dorm-room bullshit sessions are nothing more than that, and the movie never lets Allen and company relax in this hothouse of homoerotic camaraderie; they’re too busy posing on pedestals.

This stridently unsubtle film is afraid of showing the dull business of writing, yet I prefer its quieter moments—Allen’s proud father (David Cross) reading his college admissions letter; the tart disapproval of Kerouac’s neglected girlfriend (Elizabeth Olsen); or Allen finally summoning the nerve to cruise a sailor in a gay bar. Unlike Ginsberg’s poetry, Kill Your Darlings seems to have been written in all-caps. Brian Miller

Spinning Plates

Runs Fri., Nov. 15–Thurs., Nov. 21 at Varsity. Not rated. 93 minutes.

While the idea of a food documentary about three extremely varied places—a 150-year-old small-town country kitchen, a mom-and-pop Mexican joint, and a three-star Michelin restaurant—seems interesting, the delivery here is surprisingly sluggish.

That’s not the chefs’ fault. What comes across in Joseph Levy’s film are the different yet equally compelling connections that these cooks have to their food. The family-run Breitbach’s in Iowa serves as the backbone of the community, a social hub where locals gather as much for the company as for the fried chicken and homemade pies. At Tucson’s La Cocina de Gabby, cooking is what binds a family together; at Alinea, it’s the artistic outlet for Chicago chef Grant Achatz, who’s risen from the kitchens of Thomas Keller and Charlie Trotter to become a kind of Howard Roark-ian figure. But also like Roark in The Fountainhead, Achatz ultimately comes across as a caricature. Here’s the culinary renegade creating nitrous-frozen olive-oil lozenges; throwing spices and smearing fruits onto tablecloths with Jackson Pollock-like flourishes; building fork sculptures on which to serve his esoteric creations. When things turn against him, sadly, we almost don’t like him enough to empathize.

Though Spinning Plates tries to establish a cohesive thread among these three restaurants and their proprietors, our attention is sliced too thin. Also, to manipulate our heartstrings, Levy too-carefully edits the catastrophes, emotionally ambushing us in the film’s final third. You haven’t gotten to know these people well enough to genuinely feel their losses or cheer their victories.

To its credit, Spinning Plates isn’t as bombastic and unrealistic as the Food Network. Still, I left this quiet documentary feeling hungry for more. Nicole Sprinkle

Sunlight Jr.

Runs Fri., Nov. 15–Thurs., Nov. 21 at Sundance. Not rated. 95 minutes.

A minimum-wage drama, Sunlight Jr. is an account of people who mean well, work hard, and still can’t make it. The title is a particularly bitter piece of irony, because the lives of this group of South Floridians couldn’t be less cheerful at the moment. Sunlight Jr. is the name of the convenience store where Melissa (Naomi Watts) holds down a cashier job. It’s dull work, but she hopes to snag a place in the company’s college-placement program—if only she can withstand the lazy harassment of her manager and the threat of a transfer to the dreaded graveyard shift.

Melissa lives with Richie (Matt Dillon), a boozy paraplegic. These two make the film’s early reels promising, especially for the way writer/director Laurie Collyer (Sherrybaby) treats this relationship: Melissa and Richie are affectionate, clumsy, sexual. They don’t live their lives in a smart way, but they care for each other despite the truly tough hand they’ve been dealt—not just his injury, but a general cloud of socioeconomic misfortune. A variety of challenges and opportunities come their way, including the predatory behavior of Melissa’s drug-dealing ex (Norman Reedus, from The Walking Dead) and the dismal example of her mother (a blowsy Tess Harper). The presence of movie stars Watts and Dillon means we won’t take any of this for documentary footage, but Collyer’s realistic method veers close to recreating the maddening behavior of self-defeating folk in reality-TV shows.

Collyer’s sympathy for her hard-luck characters is admirable, although it’s tough to cast glamorous actors in these roles and expect her dreary, kitchen-sink world to ring completely true. The going-nowhere lives are maybe a little too easy to caricature, and the sheer misery of this trap is grueling indeed. The only thing that truly clicks is that central relationship, its moments of unexpected tenderness and support; if only Melissa and Richie could tune out the rest of the world and need nothing of it. But the rest of the world keeps intruding, and it ain’t pretty. Robert Horton

E

film@seattleweekly.com