Opening ThisWeek

PAlien Boy: The Life and

Death of James Chasse

Runs Fri., March 7–Thurs., March 13 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 90 minutes.

Seen during last fall’s Local Sightings Film Festival, this Portland documentary was my top pick—and the jury-award winner, hence its return engagement. The 2006 death in police custody of homeless schizophrenic James Chasse will inevitably remind viewers of our own SPD shooting of John T. Williams in 2010. It also has echoes in last fall’s fatal stabbing of a Sounders fan in Pioneer Square by Donnell D. Jackson, evidently also a schizophrenic failed by the system.

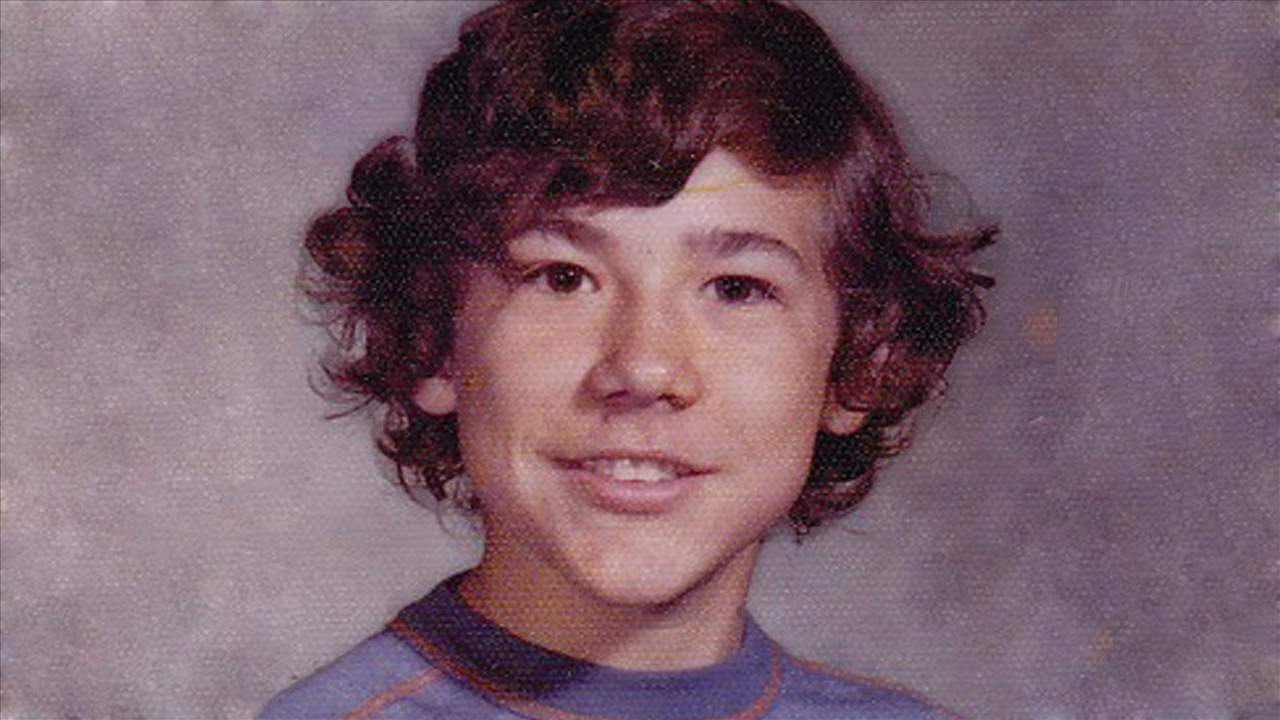

Is there a culture of aggro cops, both here in Portland, that Mayor Ed Murray and our next police chief need to address? Alien Boy strongly suggests so. In Portland’s trendy Pearl District, the frail 42-year-old Chasse is football-tackled to the pavement by a cop for peeing in public. A dozen ribs are broken, a lung is punctured, Chasse is hogtied and taken to the station, and he soon dies of respiratory arrest. At the time, Chasse was a shy, fearful man living in assisted housing who loved coffee shops and the library. Friends and family tenderly recall an avid music fan during the punk-rock ’80s who published a zine, then succumbed to schizophrenia as a teenager.

Director Brian Lindstrom spent a half-dozen years following public demands for police accountability and the ensuing lawsuit against the city. Depositions and station-house videos are damning, though Lindstrom grants a police-union rep space to respond. Incoming mayor Sam Adams eventually fires the old police chief; but as in Seattle, street-level cops are maddeningly untouchable—they have all the protections and benefits that Chasse was denied in his unhappy life.

Eight years later in a different city, our new mayor can’t seem to get a handle on police discipline. Alien Boy is a film that Ed Murray and his next police chief should be required to be see. It ought to be mandatory viewing for all Seattle cops, veterans and rookies alike. Peeing in public is a nuisance, not a crime. And as this city grows ever richer yet more stratified between Amazon workers and those seeking shelter bunks (or sleeping beneath the viaduct); as taxpayers seem unwilling to fund needed mental-health services for the homeless, our sidewalks will increasingly be shared with the indigent, the mentally ill, and those committing illegal acts both large and small. James Chasse was a sad casualty of that economic conflict, a small, weak man whom the authorities deliberately chose not to protect or serve. Brian Miller

PChild’s Pose

Opens Fri., March 7 at seven gables. Not rated. 112 minutes.

Something happened on a dark road outside Bucharest, and a boy is dead. We will not learn the details, because that’s not the point of Child’s Pose. The point is watching how character, class, and family dynamics twist the aftermath of a tragic event. There are no scenes of screeching wheels, because this Romanian movie is a series of scenes of people talking in rooms—a tough sell for a publicist, but a compelling experience when the stakes are high and the portrait of human nature is clear-eyed. As it is here.

The dead adolescent, a kid from a peasant family, was running across the road when a car driven by Barbu (Bogdan Dumitrache) hit him. Barbu was trying to pass another car and probably speeding. Under ordinary circumstances he’d be a sure bet for prison, but ordinary circumstances do not include his mother Cornelia (Luminita Gheorghiu), an elegant but ferocious upper-class woman determined to control this situation—just as she’s controlled every other aspect of her grown son’s life. In a simpler film, Cornelia would be a wicked witch strangling Barbu with apron strings (let’s cast Jane Fonda there) or a mama bear fighting for her child against all odds (Sally Field). In Child’s Pose, she is both.

Cornelia sashays into the police station the night of the accident, still wearing fur from an evening out, and promptly takes over the investigation. She reeks of clueless entitlement (her conversation with her maid is a small gem of generosity laced with manipulation), yet you’d want her on your side in a street fight. For his part, Barbu is anything but sympathetic, a cowardly sluggard who might be better off going to the clink. Gheorgiu’s performance (she’s been in a bunch of the best movies of the ongoing Romanian New Wave, including The Death of Mr. Lazarescu and 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days) captures Cornelia with brittle, I’m-still-standing exactitude.

Child’s Post is directed by Calin Peter Netzer, who uses the house style of recent Romanian film: long scenes rendered in something close to real time and deadpan treatment of bureaucracy and social conventions. As we reach the long final sequence, the ending is not at all predictable. After all the talk, it will come down to a conversation we don’t hear—but witness nonetheless—to suggest a resolution. That’s precisely how to do it. Robert Horton

PElaine Stritch: Shoot Me

Runs Fri., March 7–Thurs., March 13 at Sundance Cinemas. Not rated. 80 minutes.

The core audience for this showbiz documentary is self-selecting: If you’ve heard of the Broadway legend, age 87 at the time of filming, then you will go see the movie and be entirely delighted. Produced by Alec Baldwin, an admirer who played Stritch’s son on 30 Rock, this is emphatically a tribute to old-school musical-theater prowess. Caustic, profane, and generally averse to self-pity, Stritch is a woman whose fame never reached far beyond the Hudson. Her cabaret residencies at the Carlyle and interpretations of Sondheim endeared her to a certain kind of fan; and those fans are fading along with their alcoholic, diabetic doyenne.

Still, it’s not all sadness and nostalgia as Stritch prepares for a new show (all Sondheim, natch), grudgingly tolerates the camera of director Chiemi Karasawa, and collects praise from her Broadway epigones (Baldwin, Tina Fey, Nathan Lane, James Gandolfini, etc.). She wears her legend blithely, but never lets you forget she’s a legend. Her photo albums and polished stories are suitably glamorous (JFK tries and fails to seduce her), yet this is equally a portrait of aging—of working to the end, of the structure and dignity that work provides. We see this trouper’s slips in rehearsal and watch her tell the audience, “If I forget my lyrics, fuck it!”

Now 89, Stritch has no children; her assistants, AA buddies, and band compose her family. There can be no larger-than-life stars without such patient devotion. In this affectionate profile of a wonderfully cranky old broad, Karasawa is careful to veer her camera toward those just outside the spotlight. Stritch’s music director, Rob Bowman, for instance, vamps at the piano while she grasps for a lyric—mugging quite effectively to the audience, it must be said—and later gets the satisfaction of reading Stephen Holden’s review in the Times. Not all of us can make showbiz history, but some can still be a part of it. Brian Miller

Stranger by the Lake

Runs Fri., March 7–Thurs., March 20 at SIFF Cinema Uptown. Not rated. 97 minutes.

How well do you know this guy? The same question applies to straight weddings in proper Episcopalian churches and gay cruising encounters in the woods. It’s in the latter milieu, a hothouse monoculture, that Stranger takes place. Written and directed by Alain Guiraudie, this slow, quietly disturbing French film is no thriller. Don’t expect echoes of Hitchcock or Chabrol. The killer’s identity is obvious; the guy who falls for him is handsome and kind; and the film’s sole voice of reason is a sad, chubby closet case who observes the cruising rituals from his lonely, pebbled peninsula. Here, sex is for the taut young bodies who dare dive into the lake, not for the timid old nellies who observe from the shore.

There is a lot of cock on display in Stranger—mostly flaccid, sometimes erect, occasionally spewing—but not a lot of moral passion. Franck (Pierre Deladonchamps) witnesses a murder-by-drowning, but reports nothing to the authorities. Neither do his cruising cohort say anything about the beach blanket and car that remain unclaimed for days afterward. Franck has a crush on the sinister, mustachioed hunk Michel (Christophe Paou); to go the cops would be to hurt his chances with him. But inevitably the police come calling. “One of your own was murdered, and you don’t even care?” asks the fidgety inspector.

The movie, like Franck, answers the question with a shrug, and that may be its greatest—and only—discomfiting quality. Michel is the shark in a pool into which men knowingly throw themselves. Whether he’s an AIDS metaphor is up to you, though this eerie complacency among the cruisers makes me think of that old ’80s slogan: “Silence equals death.” Franck and company don’t want their idyll interrupted, so they evade most of the cop’s queries. Consequences, like the outside world, don’t figure here. Guiraudie’s drama never leaves the lake, and there are only a few passing references to jobs and dinner dates in town. Franck may speak of love and the desire for a companion back home, yet he keeps coming back to the woods, where a man waits with a knife. Brian Miller

300: Rise of an Empire

Opens Fri., March 7 at Sundance and other theaters. Rated R. 102 minutes.

The weather in Greece always looks so nice—sunny skies, white-sand beaches cooled by gentle zephyrs. Which means either climate change has messed with Greek weather in the past 2,500 years, or the makers of the 300 movies are taking artistic license: As befits a graphic-novel adaptation heavy on blood-spilling and war-mongering, the computer-generated skies of this world are perpetually roiling with black clouds and gloomy foreboding. 300: Rise of an Empire is based on Frank Miller’s Xerxes, and it provides a sequel to the 2006 hit 300.

Or not quite a sequel, exactly: This is a rare instance in serial-making in which the action actually takes place at the same time as the events of the first film. 300 was devoted to the battle of Thermopylae, the fabled 480 B.C. fracas in which a small contingent of Spartan warriors sacrificed themselves to hold back the invading Persian army. Rise of an Empire shifts the action to sea, where the Athenian general Themistokles (Sullivan Stapleton) leads his ships into battle against the Greek turncoat Artemisia (Eva Green, from Casino Royale), who has allied herself with the Persians.

Many bone-crushing battles ensue. Director Noam Murro, a TV-commercial veteran, apes the style of the first 300, with its geysers of digital blood splashing across the lens and its hiccuping slow-motion—sometimes in mid-decapitation, to savor the effect. These are tiresome, and one waits impatiently for Green’s imperious, kohl-eyed she-devil to stride into the scene and devour men whole. She doesn’t literally do that, of course, but the effect is the same. There’s also Lena Headey, returning from the first movie and as full of bravado as before. (We see a couple of glimpses of her character’s hubby, played by Gerard Butler, in old footage.)

In fact, despite the overwhelming—and perhaps overcompensating—masculinity that dominates these films, the appeal here is almost entirely thanks to the two women. The promise of a showdown between them is sadly unfulfilled—and would of course be historically inaccurate, if you’re still clinging to such old-timey notions. Meanwhile, the array of six-pack abs that brought the first film a certain level of pop-culture notoriety is still in place, pumped up for 3-D in some theaters. The brave few at Thermopylae did not die in vain. Robert Horton

Tim’s Vermeer

Opens Fri., March 7 at Sundance and Lincoln Square. Rated PG-13. 80 minutes.

How did Vermeer do it? This question is apparently important to some people, including a Texas millionaire named Tim Jenison, the founder of NewTek. Jenison decided to prove that the 17th-century Dutch master must’ve had help from special lenses and mathematical devices to create his luminous canvases, so he sets out to replicate the hypothetical methods by which Vermeer might have turned the trick.

The word “trick” is key here, for Tim’s Vermeer is by magicians Penn and Teller (offscreen friends of Jenison). Teller directs, and Penn Jillette acts as producer and—of course—garrulous narrator. Entertainingly, the movie tracks the months Jenison spent on his quest: first researching Vermeer’s techniques, then sitting down to try to paint a Vermeer. He arranges a room with vintage bric-a-brac and northern light; he creates the kinds of paint that Vermeer would have used in the 1600s; he grinds the kind of lenses he thinks Vermeer might have employed to enable his paintings’ near-photographic precision. Jenison’s geekiness is likable, and he makes an affable companion for this process. (He admits at one point that the job is so painstaking he probably would have given up if not for the documentary being made.)

The film’s premise isn’t revolutionary—more than a decade ago, David Hockney popularized the idea that some of the great realist painters must have used a camera obscura or other optical devices to achieve their uncanny masterpieces. (Hockney appears in the film, intrigued by Jenison’s new wrinkle.) Tim’s Vermeer has the same attitude, as though Penn and Teller—sleight-of-hand artists to the core—need to expose Vermeer’s cheat. Magicians, of all people, know there’s no actual magic, just the execution of a trick. So of course Penn and Teller would be flummoxed by genius. This kind of historical inquiry is interesting, but the impetus behind it feels a little like the persistent efforts to demonstrate that Shakespeare didn’t write the works of Shakespeare. There’s something undemocratic about the idea of genius, so the debunkers must disprove the romantic idea of the artist holding his thumb in front of his eye and miraculously solving the problems of perspective and light.

When Jenison finishes his meticulous task, what he has is a trick. It’s a pretty object, cleverly executed—but it isn’t a Vermeer. Robert Horton

E

film@seattleweekly.com