Opening ThisWeek

Draft Day

Opens Fri., April 11 at Sundance and other theaters. Rated PG-13. 110 minutes.

Kevin Costner came late to the Hollywood party, minting his stardom in his 30s with hits like The Bodyguard and his Dances With Wolves. By 40 and Waterworld, audiences grew tired of his earnest, humorless heroism. Now pushing 60, despite nice character work in The Upside of Anger and Man of Steel, he still clings to the same square, virtuous leading-man template that isn’t really interesting anymore. His NFL team manager, Sonny Weaver of the Cleveland Browns, keeps insisting “Let me do my job,” as if mere competence—and listening to his gut, of course—were all it took to succeed in today’s marketplace (be it football, finance, or flipping burgers). The gimmick here, and it’s a good one, is the ticking clock, a finite period of time in which NFL teams can draft or trade top college prospects, now a fairly data-driven process. Yet Sonny resists the usual metrics, which annoys his coach (Denis Leary) and the team owner (Frank Langella), and confounds his secret girlfriend (Jennifer Garner), also on the Browns staff, and conveniently pregnant. Slickly directed by the veteran Ivan Reitman, this is a very NFL-authorized product, and it duly celebrates the league and its loyal fans. (Our Seahawks figure in the plot, thus some lovely stock footage of Seattle.) Here is the glory of the gridiron, without the eccentric underside celebrated in Costner’s best sports movies—Tin Cup and Bull Durham (both created by Ron Shelton). Even if Sonny isn’t a numbers guy, Draft Day simply plays the percentages. Brian Miller

Exhibition

Runs Fri., April 11–Thurs., April 17 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 104 minuTes.

Form follows function in this modernist house on a quiet street in London. Stacked in clean, streamlined boxes, its floors are wrapped in glass. It is home to two artists, who work in different sections of the house and communicate through an intercom. We don’t have to watch long to intuit that the house is like their marriage: compartmentalized but comfortable, hiding its share of secrets despite the great views in every direction.

The home, a real place designed by architect James Melvin, is the primary location for this new film by British director Joanna Hogg. Hanging over the action—if “action” is the right word for this immersive, elliptical movie—is a pending sale of the home, which has put the spouses on different sides of the fence. He’s ready to move; she is hesitant. (Tom Hiddleston shows up briefly as a real-estate agent.) The two lead roles are played by non-actors: The wife, known as D, is played by Viv Albertine, onetime member of Brit-punk band the Slits; husband H is played by artist Liam Gillick. The one-off performances are completely credible. The two remain physical with each other, albeit with a few quirks. He’s stymied by her reluctance to share her working methods, which she chalks up to his tendency to pass judgment. We see her more often by herself, frequently trying out strategies for her performance art while tentatively allowing the neighbors to see what she’s up to through the windows.

I think that’s what she’s doing, anyway. Exhibition does not spell out its purposes, at least not often. It comes as a relief, after H and D have gone to a dinner party across the street and D has had a fainting spell, when we hear them talking about the spell being a tactic for escaping dull company. Other sequences, equally inscrutable or vaguely alarming, are left unexplained. All of which will undoubtedly annoy some unsuspecting viewers, although for the most part Hogg has made a consistently intriguing movie. Maybe it’s the sense that something serious has happened in the past, and remains coursing beneath the surface through the most mundane sequences. Maybe D knows that their world will collapse when they give up this unique domicile. Maybe H knows that, too; maybe that’s why he’s pushing for it. Whatever they are thinking, after they move out of the place, I give the marriage six months. Robert Horton

PFinding Vivian Maier

Opens Fri., April 11 at Seven Gables. Not rated. 83 minutes.

The biggest discovery of 20th-century photography was made in 2007 by Chicago flea-market maven/historian John Maloof. Vivian Maier was a nanny who died soon thereafter, indigent and mentally ill, a hoarder. Maloof bought trunks of her negatives with no idea what they contained. The revelation of those images, in a series of art shows—including at Photo Center NW last year—and books, immediately placed her in the front rank of street photographers like Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand. But who the hell was she?

Now Maloof and Charlie Siskel have directed a kind of documentary detective story about the enigmatic spinster (1926–2009). It’s an irresistible quest, as Maloof interviews the now-grown kids Maier cared for, plus a few fleeting friends and acquaintances, who had no idea of her gifts. I don’t want to spoil the sleuthing in this sad, intriguing movie, which also functions as a sales reel for more books and shows to follow from a massive archive that’s still being indexed and printed. Maloof has become a one-man industry on Maier’s posthumous behalf: curator, champion, and businessman. Maier’s prints are selling in a way those of the tired icons of the last century are not; she’s trendy not just because of her eye—excellent, with many new (to me) images included here—but because of her mystery.

That’s where, despite the film’s art-history appeal, I part ways with Maloof. Do we really need to know an artist—Frank, Winogrand, Diane Arbus, whomever—to appreciate their work? Why must there always be psychology on the other side of the lens? Maier was almost pathologically secretive (“sort of a spy,” she said), but all photographers hide behind the camera. Would she have wanted her images seen by the public? Maloof conclusively answers that question. Would she have wanted his movie to be made? All her grown charges say the same: No. Brian Miller

Ilo Ilo

Opens Fri., April 11 at Varsity. Not rated. 99 minutes.

Nearly 10, Jiale is a nightmare of an only child: selfish, spoiled, ungrateful. His mother, a Singapore office clerk, is pregnant with baby number two, which may explain Jiale’s acting-out at home and school. His father is in sales until he’s not. It’s 1997, and Asia is plunging into economic crisis, which matters not a whit to Jiale, an obsessive student of lottery numbers, until his busy parents hire a Filipina live-in maid to care for the household and him. Suddenly there’s a new focus for this petulant boy (Koh Jia Ler): his vehement opposition to “Auntie Terry” (Angeli Bayani).

Anthony Chen’s worthwhile drama (his debut) makes Jiale neither unbearably horrid or, when patient Teresa finally wins him over, unbearably cute. He’s just another self-absorbed kid who can’t understand how the globalized economy is making pawns not just of Teresa but his parents, too. The script is based on Chen’s own experience with a Filipina nanny, and we see how an ethnic and religious outsider is gradually drawn into the intimate rituals of a Chinese home. (Dad wanders around obliviously in his tighty-whities until Teresa giggles.) The Lim family and their servant communicate in English (with subtitles), and this peculiar mixing of cultures points to Chen’s larger point—the economic interdependency of Asia, with its close proximity of cheap labor and wealthy cities. Even as we watch the Lims slipping out of their middle-class bubble, we also learn from Teresa’s pay-phone calls that she has family back home. She works abroad and surrenders her passport because she must; and Jiale’s father is soon also forced beneath his station.

That Ilo Ilo—a childish transliteration of Iloilo province in the Philippines—is set 10 years before the global financial crisis gives it a small, sad, prophetic power. Think of all the Mexican migrants ebbing across our border, the Eastern Europeans doing menial work in the West, the desperate Africans drowning in the Mediterranean. Teresa is a member of the same bottomless sea of unskilled workers that sloshes around the planet. Brian Miller

PLe Week-End

Opens Fri., April 11 at GUild 45th. Rated R. 93 minutes.

If a British couple making a misguided trip to Paris to save their marriage sounds like a cliched plot, rest assured it’s not. This is no midlife crisis movie a la Woody Allen or Judd Apatow. In fact, our protagonists are past middle age, in their 60s even—an age group that most films avoid like the plague. (Unless they star the likes of Diane Keaton or Alec Baldwin bumbling through one slapstick joke after another.) Instead, we meet still-beautiful Meg (Lindsay Duncan) with her sculpted cheekbones and long blonde hair, and Nick (Jim Broadbent), a sweet, goofy-ish philosophy professor who confesses on the trip that he’s just been sacked from his job.

From the first scene their dysfunction is evident: Arriving at a third-rate hotel, Meg’s silent fury at Nick grows hysterical as she huffs off, hails a cab, and checks them into a gorgeous suite at a luxe hotel. From there, the weekend perfectly encapsulates this trenchant quote from Liane Moriarty’s novel The Husband’s Secret: “Marriage was a form of insanity; love hovering permanently on the edge of aggravation.” As Nick makes one loving overture after another, Meg’s aggravation with him—and downright cruelty—becomes increasingly palpable, even as she tries to check it. When Nick falls on the street and badly hurts his knee, she runs to him, the worried wife trying to help him up—yet ultimately walks away scoffing at his weakness. (Their push-pull dynamic is expertly rendered by the veteran team of director Roger Michell and screenwriter Hanif Kureishi, previous collaborators on The Mother and Venus.)

Despite Nick and Meg’s 30-year rut and the loathsome jabs that result, there are exquisite moments of levity, like when they dine and dash at a pricey Parisian restaurant, or chase each other through the halls of their grand hotel. Also here are unexpected moments of passion: a long kiss on the street, an almost discomfiting scene of sexual masochism. The weekend culminates at a posh dinner party thrown by Nick’s old Cambridge buddy, played appropriately neurotically by Jeff Goldblum, where both this marriage’s frailty and its endurance are beautifully, achingly captured. Nicole Sprinkle

POn My Way

Opens Fri., April 11 at Sundance. Not rated. 113 minutes.

Femme d’un certain age Bettie Chapoutier is beleaguered by some very French problems: Her bistro is failing, and her lover—she’s been waiting for years for him to leave his wife—instead takes up with some queue-jumping 25-year-old. Bettie doesn’t intend to run away from all this, but one afternoon I’m-just-going-for-a-drive turns into a road trip, and that carpe diem adventure (among other things, she hooks up with a skeezy guy half her age, at most) turns into a surprise opportunity to reconnect with the grandson she barely knows and the troubled daughter she knows all too well.

Bettie is played by Catherine Deneuve, whose face, I don’t need to tell you, is one of the wonders of cinema history, and is photographed accordingly by director Emmanuelle Bercot—not prettified, but allowed the ravishing dignity of looking its age. A subplot concerns Bettie’s being inveigled into attending a reunion of beauty queens; loath to think her life might have peaked as Miss Brittany 1969, Bettie at first refuses. But—and this too is so deliciously French—the reunion is portrayed without a molecule of camp, instead filmed as a bouquet, a banquet, of dozens more magnificent faces, as if Deneuve was a priceless pearl placed in an exquisite jeweled setting. And screenwriter Bercot also grants Bettie a final scene that’s a surprise not in terms of plot, perhaps, but in tone: a fizzing, slightly absurd, sparkling-rose sort of joy until then absent from the film but which suddenly seems like the only possible capper. Gavin Borchert

The Raid 2

Opens Fri., April 11 at Sundance and other theaters. Rated R. 148 minutes.

When The Raid 2 bowed at Sundance earlier this year, it triggered an instant-analysis debate along a narrow spectrum. Was it the greatest action movie ever made, or merely the most violent? Considering the film’s target audience, that’s a win/win argument. Gareth Evans’ sequel to his culty 2011 The Raid: Redemption, which was set primarily within a Jakarta high-rise, considerably widens the canvas this time out. Returning hero Rama (Iko Uwais) has survived that adventure only to be tapped for an undercover operation as unlikely as it is brutal. He’s spent two years in jail earning the trust of an Indonesian gangster’s son (Arifin Putra), the better to infiltrate the gang when he gets out. The aim is to gain information about police corruption and smash the syndicate, but Evans seems less interested in the intricacies of storytelling than he is in devising one flabbergasting action sequence after another.

This he does, with utter confidence, for two and one-half hours. This is far too long by ordinary standards, but not too long if you a) have an appetite for unbridled mayhem, or b) curiosity about the spectacle of a director playing can-you-top-this with himself. On the latter point, Evans frequently succeeds, staging an awe-inspiring car chase, a massive donnybrook in a muddy prison yard, and a climactic hand-to-hand fight in a state-of-the-art kitchen that uses each utensil for maximum effect. We’d also like to introduce you to a couple of characters who lurk around the edges waiting to deliver their specialties: Hammer Girl and Baseball-Bat Man. Given the expectations raised by their billing, they do not disappoint. There’s also a fantastically cool old-school assassin (Yayan Ruhian, sharing fight-choreographer credit with Uwais) who really deserves his own spinoff vehicle.

Before that comes, Evans will undoubtedly deliver Part 3 of this series—or so the ending suggests. It’s hard to know where that movie would go, given the maximalist treatment here: The fights are breathtaking, the stunts a hoot, and a few of the most violent moments are shockingly grisly. The Raid 2 is some kind of pulp achievement, but it doesn’t really make you eager for more; except for die-hards, exhilaration could surrender to exhaustion just after this movie gets out of the kitchen. Robert Horton

The Retrieval

Runs Fri., April 11–Thurs., April 17 at SIFF Film Center. Not rated. 94 minutes.

It would be cynical to suggest that this sound little drama about fugitive slave hunters, set during the late Civil War, is riding the coattails of 12 Years a Slave. Let me put it differently: Chris Eska’s indie feature wouldn’t be released in theaters were it not for the new interest in that fraught chapter of American history. The plot you know from countless Westerns and such: An impressionable youth on a perilous journey, mentored by two father figures—one a scoundrel, the other a man of integrity.

Will (Ashton Sanders) is a 13-year-old whose parents have disappeared into the plantations. He and Marcus (Keston John) are the two black members of a white bounty-hunting gang that uses them as bait. They’re paid a few coins to betray their kind, but the ringleader clearly has the power of death over them, too. Will feels compelled to obey, even when he and Marcus are sent north over the border—the film was shot in Texas, though the story isn’t region-specific—to entice Nate (Tishuan Scott) back to the land of shackles (or worse).

On this rural odyssey, our trio walks off the paths where whites and soldiers might be encountered. Their existence is liminal, and we’re unsure where the border lies. The grass, trees, and swamps provide no clue, since all men ought to be free in this natural domain. Only Nate feels confident here. “I ain’t a runaway,” he tells Will, who’s awed to meet a free black man—probably the first he’s ever encountered. (Nate’s also lethal with a tomahawk, which helps make an impression.)

Rather than burrowing into the psychological anguish of one particular slave, as in the recent Oscar winner, this is a more archetypical tale—solemn and familiar, with an outcome that seems older than slavery itself. Brian Miller

Under the Skin

Opens Fri., April 11 at Harvard Exit and Sundance. Rated R. 107 minutes.

Yes, this is the movie where Scarlett Johansson gets naked and—playing an alien huntress cloaked in human skin—lures men to their deaths. Let’s get that out of the way early. Adapting a 2000 novel by Dutch writer Michael Faber (not really a sci-fi guy), Jonathan Glazer dispenses with suspense or context. Instead we have process. Aided by some motorcycle-riding minions, Johansson’s unnamed character functions like part of the same hive-mind. She’s more worker bee than killer, a drone programmed to do one particular thing. This consists of driving around Scotland in a white van, calling out to single men with a posh English accent, then leading them back to her glass-floored abattoir. Her victims follow willingly and seem to die painlessly. (Also naked and erect.) Not only is the eerie, affectless Under the Skin not really sci-fi, it’s not really horror, either.

So what is it then? British director Glazer emerged from commercials and music videos with Sexy Beast (2000), stumbled with Birth (2004), and now follows Faber into what Descartes called the mind/body problem. How can we know what another person is thinking? How can we be certain our own solitary consciousness isn’t unique in a world of replicants placed here to fool us? Because humankind is, if you study our physical form long enough, profoundly odd. As it certainly is to Johansson’s alien, who’s constantly scrutinizing her prey: Is he big enough, meaty enough, a suitable delicacy to be slaughtered and beamed back home? Personality or psychology count for nothing; it’s Descartes in reverse. She cares only for the body, and she’s learned only enough of our language and social protocols to flirt and deceive. In the film’s most chilling scene, she drags a victim to her van, ignoring a crying toddler on the beach. Why not grab this little morsel, too? It’s not big enough, not worth the effort for an apex predator. (She’s no cannibal, however, since she’s not hunting her own kind.)

Eventually Johansson’s visitor goes rogue, apparently having been inspired to empathy—or maybe just bloodless curiosity—after picking up a disfigured hitchhiker. Under the Skin then becomes a dilatory chase movie, without much action, as her brood tries to return her to the nest. Johansson is suitably blank (and gorgeous) for her dispassionate role, with several scenes filmed with ordinary Scots who were unaware of the hidden cameras. Out of her van, she’s disoriented and vulnerable, panicking when a gaggle of women drags her to a disco. (You see terror in her eyes: Am I being led to the slaughterhouse, too?)

Standing in a full-length mirror, studying her nude body, the huntress flexes her knees and joints, bends and stretches her unfamiliar physique (really more of a carapace or housing, like a snail shell for her protean being). What is this strange thing I’m wearing? Is that all it takes to trap these stupid men? Why do they want me so badly? What would food or sex actually feel like? Such questions never would’ve occurred to the illegals in Men in Black or the predator in Predator. Intelligence is here vying with instrumentality. If this alien can question her role, consider her apartness from the hive, might she then have a soul? Brian Miller

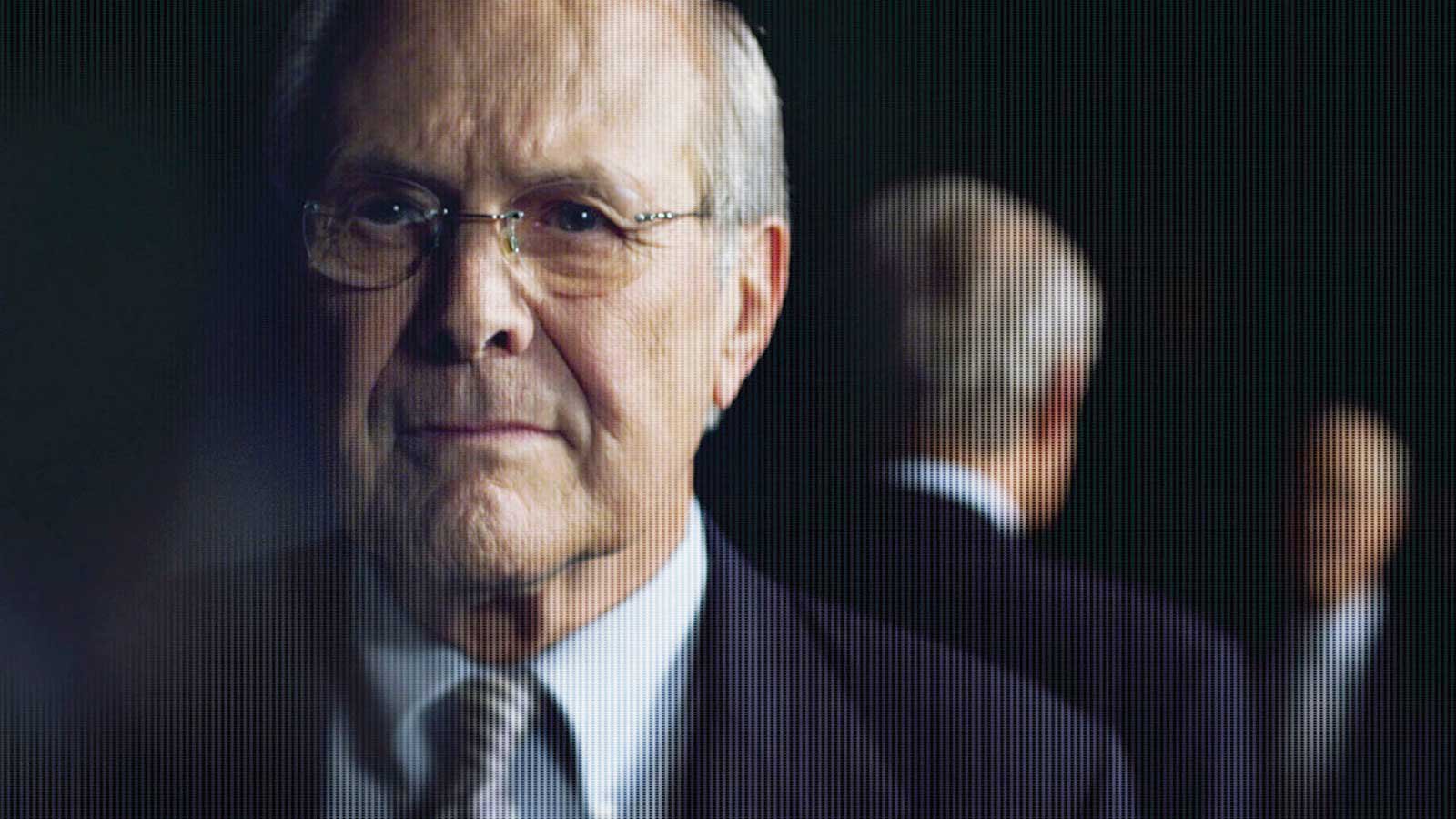

The Unknown Known

Opens Fri., April 11 at Sundance. Rated PG-13. 102 minutes.

The conceptual appeal is unmissable: Having won an Oscar for his 2003 The Fog of War, a study of Vietnam War architect Robert McNamara, documentary giant Errol Morris would naturally turn to another controversial U.S. Secretary of Defense for a bookend project. The subject here is Donald Rumsfeld, who held the job during the commencement of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Rumsfeld became famous for his loquacious (at times downright hammy) press conferences, when the sound of his own voice would lead him through ever-expanding circles of rhetoric—a Yogi Berra elevated to a position of life and death. Thus his classic formulation: “There are known knowns . . . There are known unknowns . . . But there are also unknown unknowns.”

I always thought that was one of the more sensible of Rumsfeld’s puckish quotes. But—at the risk of sounding Rumsfeldian—it does give a glimpse into a mind in which even uncertainties are something to be certain about. And this is what makes The Unknown Known something of a non-starter as an Errol Morris film. Rumsfeld is utterly tranquil in his aphorisms and his conviction. The fog of war? There isn’t even a faint mist in Rumsfeld’s mind. Where McNamara was troubled by the decisions he’d made during Vietnam, Rumsfeld does not appear to have practiced introspection, or even heard of it. Nothing happens to break the surface, and Rumsfeld’s bright-eyed, unfailingly cheerful bureaucrat is unflappable in the face of Morris’ camera.

Morris supports the interview sessions with vintage clips of the man’s career, as well as sound bites from the war years. It comes to feel desperate, as though Morris knew he hadn’t gotten through to his subject and needed to fill out the program with evidence. But maybe this extended look at blandness is a worthy companion piece to The Fog of War after all. It lacks that movie’s drama; but in the absence of a breakdown or the slightest bit of hand-wringing, it allows the viewer to decide how to view this singularly unreflective person. Intriguing bits are highlighted, such as Rumsfeld’s torrent of memo-writing—some on big issues, some daftly trivial. What drives that? For that matter, why did Rumsfeld sit down with Morris for an extended interview? Morris, perhaps exasperated, asks him that question as the film nears its close. It’s the one moment Rumsfeld seems at a loss for an answer. His not to reason why; his but to be a decider. Robert Horton

E

film@seattleweekly.com