Opening ThisWeek

Better Living Through Chemistry

Opens Fri., March 14 at Sundance Cinemas and SIFF Cinema Uptown. Not rated. 91 minutes.

Sam Rockwell sightings are like spotting a wobbling comet in some oblique, unpredictable orbit. You’re never sure why he’ll show up in this movie or that, seldom as the star, and never following the obvious trajectory. The Way, Way Back gave him a surprise hit last summer, when he wore his teen-mentorship lightly. Not long thereafter, he portrayed a different kind of loner in A Single Shot, and now he plays a disaffected suburban pharmacist who’s also at odds with society. Doug Varney, like so many of Rockwell’s characters, isn’t a joiner; he’s something of a stranger to his wife (Michelle Monaghan), a health fanatic and cyclist, and teen son (Harrison Holzer), a chubby pariah at school. And another thing about Doug, also common to Rockwell’s casting: He’s a suggestible sort, a bit of a weakling, a dupe waiting for a woman to lead him astray—a femme fatale, if you will.

This brings us to Olivia Wilde as pill-popping trophy wife Elizabeth, who proves to be Doug’s undoing. Written and directed by Geoff Moore and David Posamentier, Better Living is patently modeled on old film noirs like Double Indemnity or The Postman Always Rings Twice, though it’s given an entirely larky, comic spin. Murder is discussed (here’s Ray Liotta as Elizabeth’s rich husband), crimes are committed, and there’s even a doped-up bicycle race in which Doug makes like Lance Armstrong. Still, the tone is as light as a trip to Ikea (though it gains a little texture from Jane Fonda’s droll, purring narration).

For a while, high on his own pills, power, and adultery, Doug can crow, “I’m the man behind the curtain, the wizard! I pull the strings!” But the enjoyably shallow Better Living pulls back from any real transgression or black comedy. (Recall The Details for a genuinely dark-comic take on similar material.) It’s like a John Cheever story scrubbed of the angst or consequences. On the plus side, however, the movie gives Rockwell room to dance; and for that we must be grateful. Brian Miller

PThe Grand Budapest Hotel

Opens Fri., March 14 at Guild 45th, pacific place, and lincoln square. Rated R. 100 minutes.

Some filmmakers become genres unto themselves. A “Wes Anderson movie” very quickly came to mean something specific, regardless of its definition as coming-of-age picture (Rushmore), Salingeresque family comedy (The Royal Tenenbaums), or animated kiddie fare (Fantastic Mr. Fox). If you’ve absorbed the storybook Anderson style, you won’t find too many surprises in The Grand Budapest Hotel, his eighth feature. But you will find a disciplined silliness—and even an occasional narrative shock—that vaults this movie beyond the overdeveloped whimsy that has affected Anderson’s work since The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou.

By the time of its 1968 framing story, the Grand Budapest Hotel has been robbed of its gingerbread design by a Soviet (or some similarly aesthetically challenged) occupier—the first of the film’s many comments on the importance of style. A writer (Jude Law) gets the hotel’s story from its mysterious owner, Zero Moustafa (F. Murray Abraham, a lovely presence). Zero takes us back between world wars, when he (played now by Tony Revolori) began as a bellhop at the elegant establishment located in the mythical European country of Zubrowka. Dominating this place is the worldly Monsieur Gustave, the fussy hotel manager (Ralph Fiennes, in absolutely glorious form), a man given to reciting poetry and dousing himself in a fruity cologne called “L’air du panache.” The death of one of M. Gustave’s elderly ladyfriends (Tilda Swinton) leads to a wildly convoluted tale of a missing painting, resentful heirs, a prison break, and murder. Along the way Zero meets a comely confectioner (Saoirse Ronan), allowing the writer/director to prove that a pastry shop is as ideal a Wes Anderson location as a continental hotel.

Adrien Brody and Willem Dafoe play fascist villains, and Edward Norton is a fumbling policeman. Some of Anderson’s other regulars—Bill Murray, Jason Schwartzman, Owen Wilson—flash by in cameos. All are in service to a project so steeped in Anderson’s velvet-trimmed bric-a-brac we might not notice how rare a movie like this is: a comedy that doesn’t depend on a star turn or a high concept, but is a throwback to the sophisticated (but slapstick-friendly) work of Ernst Lubitsch and other such classical directors. In films like this, behavior and personal elan are the currency that matters, a triumph that outlives the unpleasantness of dictators and storm troopers—as evidenced by the way the aged Zero still speaks worshipfully about his natty mentor. In a delightful way, Anderson is making the case for the value of his own moviemaking approach. Yes, he spritzes “L’air du panache” over his work, but in this case the combination of playfulness and gravity makes The Grand Budapest Hotel linger in the air long after it’s is over. Robert Horton

If You Build It

Runs Fri., March 14–Sun., March 16 at SIFF Film Center. Not rated. 86 minutes.

Northern liberal do-gooders come to a poor region of North Carolina to teach teenagers how to measure, design, and build things. Folks in Bertie County already know how to work with their hands, of course, since farming and industrial chicken ranching are the main forms of employment. But brain drain is an evident problem, so the local school superintendent hires Emily Pilloton and Matthew Miller for a pilot program they call Studio H. There, skeptical students are encouraged to get their fingers dirty, make design sketches, and use power tools. Meanwhile, the school board kicks out its chief and cuts the studio’s funding.

This could be the plot for a fish-out-of-water comedy, only Emily and Matthew are already a couple, and Patrick Creadon’s earnest documentary is plainly aiming for inspiration, not laughs. Emily and Matthew are relentlessly cheerful and patient, though there are moments of exhaustion and doubt (they’re surviving on grant money). The kids are a typical bunch of teens, by turns rowdy and studious, all of them flattered to be treated like peers. (Creadon, previously the director of Wordplay, doesn’t gain access to their regular classes; nor does he interview the school board members, who’ve made other questionable decisions.)

The idea of reinventing shop class is a sound one, particularly when we’re trying to resurrect American manufacturing and train a new generation of skilled workers. Emily and Matthew are like emissaries from the Brooklyn maker movement of 3-D printers and artisans with MFAs. After two years in town, they clearly make a difference to their pupils and community. Yet in the film’s frustrating postscript—do any of these graduates have jobs, by the way?—we see how even these two committed idealists must go where the funding is. And that is far from Bertie County. Brian Miller

Particle Fever

Opens Fri., March 14 at Harvard Exit. Not rated. 99 minutes.

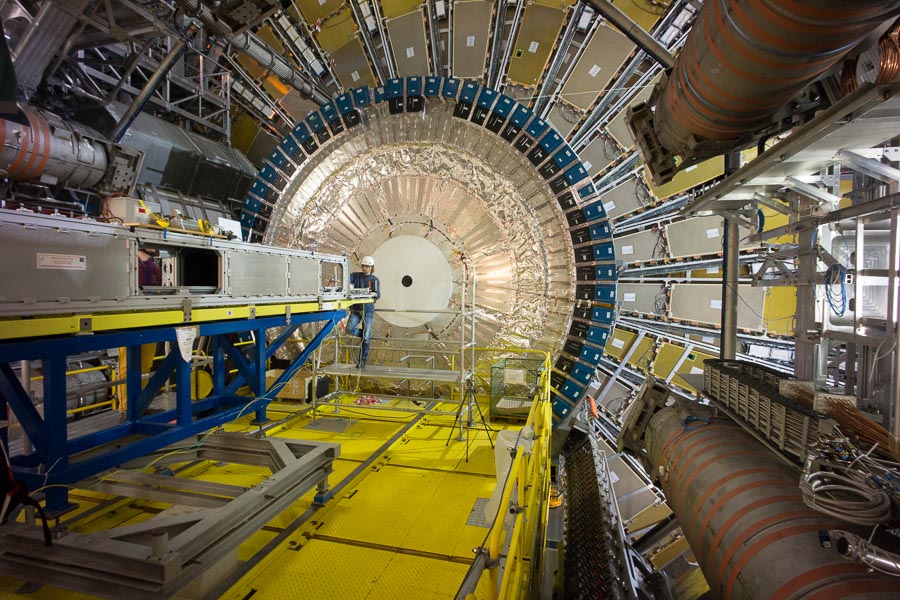

If nothing else, this documentary confirms something you’ve probably always suspected: Really brilliant physicists are almost exactly as nerdy as the average science-fiction geek. A sense of humor and issues of personal style appear to be aligned on the same spectrum in both groups, as is the ability to imagine the future in a new way. Given that reality, director Mark Levinson was probably wise to focus on the personalities working on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), that huge project near Geneva. Their quirkiness allows a human portal into the science behind this massive underground laboratory, which after 20 years of effort went live in 2008 and confirmed important results just last year.

The gist of the project—and I speak with absolutely zero authority on this—is to send protons around a 17-mile ring and smash them into one another at high speed. The result will reveal answers to ongoing theoretical questions about what the universe is made of, especially as regards the Higgs boson, the missing piece in the Standard Model of physics. We get the history of the LHC, and cameras are there when the first tiny proton makes its first circle in September 2008. Cameras are also there a few days later when a design flaw causes an accident that sets the experiment back by more than a year. We are guided in this journey by a batch of physicists, from esteemed veterans in the field to the puppy-dog enthusiasm of Monica Dunford, who treats the word “data” the way the average person might describe a Powerball jackpot. All of them are pretty much unified in their anxiety over the outcome of the LHC’s evidence. It might show them the future of scientific research, or it might prove they’ve come to a $5 billion dead end. They are less worried that the experiment could cause the Earth to vanish into a black hole, an extremely unlikely (gulp) outcome.

Levinson does a good job explaining the basis of this stuff, although one wants to know a little more about why it all matters. One possibility, that the Higgs boson would confirm that all matter isn’t in danger of falling apart at any given moment, is a welcome nugget of information. Particle Fever coasts a bit with its reliance on character study, but it contains real suspense and some tantalizing glimpses into the future. It also serves as a needed reminder of the excitement of science, a practice that need not be left exclusively to nerds. Robert Horton

Vic + Flo Saw a Bear

Runs Fri., March 14–Thurs., March 20 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 95 minutes.

French-Canadian director Denis Cote has described his method as an attempt to create a “no-comfort zone for the audience” that leaves the impression “that a film can fall apart at any second.” That’s a fair description of Vic + Flo Saw a Bear, which sustains the sense that—even in its most mundane moments—something extremely odd is about to happen. When something, at long last, truly horrifying occurs, it’s a confirmation that this little patch of the Quebec woods might not be far on the map from Twin Peaks.

Victoria (Pierrette Robitaille) has come to the forest after her release from a serious prison sentence—what her crime was, we don’t know. She shows up at her comatose uncle’s home and announces that she will now be taking care of him, an act that irritates the neighbors who’d been tending the old man. Vic is 61 and ready to live in this remote place, but her younger lover Florence (Romane Bohringer) is not so content when she arrives. Their relationship becomes rockier as the film drifts along, and an unexplained issue from Flo’s past doesn’t help matters. They receive a peculiar level of scrutiny from Vic’s parole officer (Marc-Andre Grondin), a stern young man of unexpected depth, and from an unnervingly cheerful local (Marie Brassard), whose demeanor in these backwoods is markedly different from that of the other unwelcoming neighbors.

Cote is a former film critic whose demanding output includes the haunting Curling (2010) and the eerie observational documentary Bestiaire (2012). Vic + Flo makes for compelling viewing, although the final 10 minutes invite audience backlash (or at least heated conversation), despite a strangely comforting last-minute coda. Is Cote finishing his film with a disturbing left turn for its own sake, or are we watching a fable about the way the past catches up to people? If the latter, Cote isn’t going to spell out what the past was. At first glance that seems like a perverse storytelling strategy, but maybe not. There’s only the present, and the way people treat each other, and how behavior eventually captures people in traps of their own devising. Robert Horton

E

film@seattleweekly.com