Opening ThisWeek

As Is It in Heaven

Runs Fri., July 18–Thurs., July 24 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 87 minutes.

The new spiritual leader of a small religious sect in the American South has received the word. That is, the Word. And the Word is that the group must become purified to be sufficiently prepared for the final days, which—according to their own in-house prophet—will arrive about a month hence. Along with their usual rounds of preaching and praying, this will mean intense fasting. That sacrifice will get them back up to speed for the deliverance to come.

This setup provides not only the countdown structure of As It Is in Heaven but also its style. This low-budget indie is itself purified, stripped bare, and ornament-free. We see almost nothing but the big house—where the dozen or so cult members live—and the surrounding woods and creek. We don’t find out much about the recent convert, David (the haunted Chris Nelson), who abruptly takes over the leadership of the group. His visions might be divine intervention or guilty nightmares, but either way he appears to be that most dangerous of things: a true believer. There is some tension surrounding a rival (Luke Beavers) and the possible ambivalence of a brand-new recruit (Jin Park), but for the most part the film rolls out on its sweltering-summer mood and the growing sense of escape routes closing.

As It Is in Heaven is the feature debut of director Joshua Overbay, whose name sounds like it could belong to a megachurch pastor. Although his production design is simple, Overbay is fond of the moving camera, so the film never feels static. There are amateurish performances in the mix, and at times the simplified storyline probably errs on the side of purity—one occasionally yearns for intrigue or a pinch of melodramatic spice. But for the most part this movie joins other recent cult studies (Sound of My Voice and Martha Marcy May Marlene, good; The Sacrament, not so good) in identifying the apocalyptic simmer that runs beneath current American culture. Evangelical and horror-movie makers have their own takes on that theme, but these indies seem interested in examining that need to buy into the eve of destruction. They’re serious about it, and admirably searching—although with all this careful even-handedness on display, a good Dr. Strangelove-like satire would not be unwelcome. Robert Horton

Coherence

Runs Fri., July 18–Thurs., July 24 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 89 minutes.

Eight Los Angeles friends gather for an ordinary meal, which is then interrupted by a mysterious crisis. That film was last year’s It’s a Disaster, the occasion brunch, and the outside menace some kind of plague. This time around, in James Ward Byrkit’s modestly suspenseful thriller, it’s a dinner party that happens to coincide with a comet passing close to the Earth. (No, it doesn’t awaken the dead and turn them into zombies; I’ll stop your supposition right there.) The four couples spar a bit and hint at some past sexual intrigue, but they’re a calmer, less neurotic ensemble than that of It’s a Disaster. The vibe is one of settled, contented 30-something-dom: mortgages, Priuses, and careers. These people are more than a little complacent and self-satisfied, in need of a jolt.

Then cell phones stop working and the Internet goes down, the universal tokens of crisis in any modern disaster movie. Soon the power is out, and our eight bumblers are navigating by candles and glow sticks (perhaps left over from that planned trip to Coachella that was canceled for a weekend of shopping and spa-going instead). What’s happening? One guy makes a worrisome reference to something his brother, a physicist, had warned about. They send a search party to the one house outside that seems to have electricity, but this only complicates matters—perhaps by a factor of two, maybe more on a logarithmic scale (I stopped counting at a certain point).

Certainly there’s been an indie trend toward smart, low-budget sci-fi since Darren Aronofsky’s Pi debuted at Sundance ’98 (e.g., The Signal, Safety Not Guaranteed, and the forthcoming The One I Love). Without the expensive crutch of CGI and special effects, however, your script has to be airtight. Byrkit doesn’t have the option here of cutting to alien invaders or the White House being blown up, even if he wanted to. Locked into its one-bungalow location, Coherence is essentially a chamber drama where, most problematically, the writer let his cast improvise the script. Byrkit gave them an outline, then the ensemble ad-libbed during five nights of shooting.

Such liberty is perilous for sci-fi. If anything can happen (aliens, alternate reality, “quantum decoherence,” etc.), the story has to be controlled, thought through to the very last line. Instead we get shaky dollops of post-Lost paranoia (“We’re in a different reality here”), urban folklore, Schrodinger’s cat, and references to Gwyneth Paltrow’s Sliding Doors. I’m spoiling nothing to say that a giant monster doesn’t arrive a la Cloverfield to settle things by stomping Los Angeles into ruin. But Coherence would be a much better movie if it did. Brian Miller

PA Summer’s Tale

Opens Fri., July 18 at Varsity. Not rated. 114 minutes.

The movie of the summer in 1996 should have been A Summer’s Tale, a wise and bittersweet romance by then-septuagenarian filmmaker (and French New Wave co-founder) Eric Rohmer. But it didn’t get a chance to be. While the film did enjoy a regular release in Europe and was seen at festivals, for some reason it never actually opened in the U.S. for a regular run. This absurd oversight is finally rectified, as the movie is enjoying a proper arthouse go-round at last.

A Summer’s Tale, or Conte d’ete, was the third film in Rohmer’s four-seasons cycle. (Somewhat confusingly, Rohmer’s 1986 Le rayon vert was titled Summer for the English-language market.) This one’s about a would-be musician named Gaspard (Melvil Poupaud) who travels to the Brittany seaside for a summer break before his grown-up duties beckon. Three young women are in his mind: loquacious waitress Margot (Amanda Langlet, the adolescent star of Rohmer’s great Pauline at the Beach), with whom he can talk about his problems; assertive singer Solene (Gwenaelle Simon), ripe for a summer fling; and his quasi-girlfriend Lena (Aurelia Nolin), who’s supposed to be showing up any day now. The situation is far more nuanced than this romantic choice would suggest, and Gaspard faces long days of exploring and reassessing his attitudes about romance, most of which are charmingly in error.

Nothing in the movie is glibly scenic, but the locations are beautifully and precisely captured. So is the shapelessness of youthful summer days, which could be why the movie lasts 114 minutes; if it moved quicker it might not get that drowsy quality right. And Rohmer, as always, has the touch when it comes to tracking the tiny shifts in intensity between people. His neutral camera, which generally stays far enough from the characters so that we can appreciate body language and comfort levels, is ideal for allowing us to notice the tentative brush of a bare foot against someone else’s leg or the incline of two heads toward each other in a game of chicken that will end in a kiss. Or not.

For a while there it seemed as though Rohmer might just keep making a movie a year indefinitely. But he died, in 2010, at 89. So the belated arrival of this neglected gem is an unusual pleasure—maybe even the movie of the summer. Robert Horton

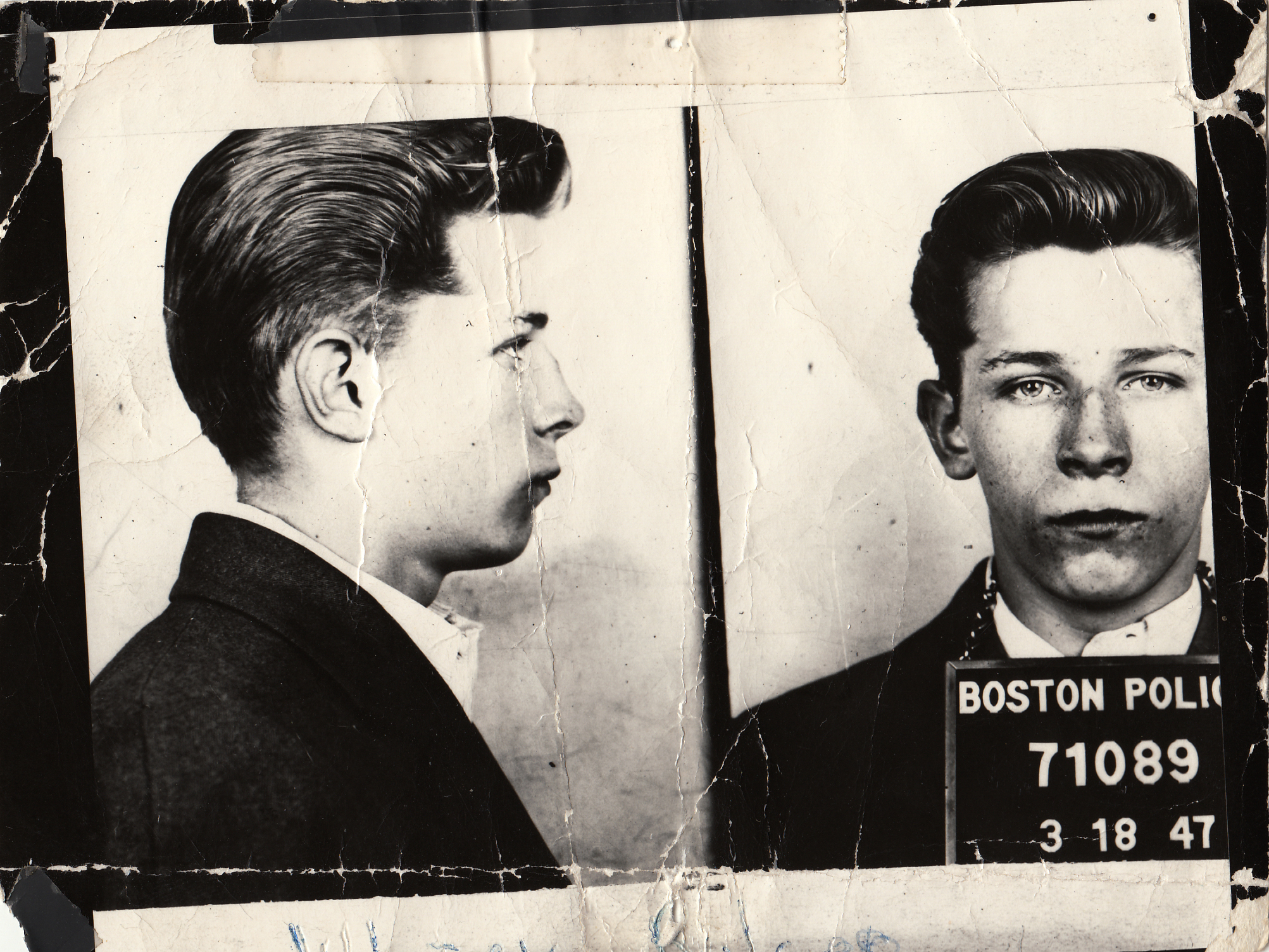

Whitey

Runs Fri., July 18–Thurs., July 24 at Sundance Cinemas. Rated R. 107 minutes.

If you grew up in Boston, the criminal legend of James “Whitey” Bulger might carry some weight, particularly if you grew up Irish Catholic in the South End. A certain kind of outlaw is made an emblem of his ethnicity: Al Capone for the Italians, Meyer Lansky for the Jews, Frank Lucas for the blacks. Their taint becomes a synecdoche for unwelcome newcomers and minorities: See, all these damn, filthy immigrants are driving up the crime rate! Right-leaning newspapers, back in the day, loved to write about such tabloid crime figures; it was a way to displace nativist sentiment with law-and-order headlines. Then, like newspapers themselves, all those legendary gangsters got old and started dying. After a life in crime that began in the ’50s, Bulger went underground in 1995—tipped off by a corrupt FBI agent to avoid arrest—and was basically forgotten until his California discovery in 2011.

A lot changed during the interim, and that’s the challenge for documentary director Joe Berlinger, whose greatest successes have come in chronicling unknown stories (Brother’s Keeper, Paradise Lost, etc.). Bulger’s case is the opposite: His arrest and 2013 trial were widely reported (the verdict: guilty). Martin Scorsese’s 2006 The Departed, though an inferior remake of Infernal Affairs, turned Jack Nicholson into a very Bulgeresque ringleader, right down to the Southie accent. Now 84, Bulger reappeared just long enough to rekindle his infamy; then he disappeared again to spend the rest of his life in jail.

Why should we care about him now? Berlinger’s thesis, which he can’t quite prove, is that Bulger was never previously prosecuted because he was a protected informant for the FBI, owing to the notorious leadership of J. Edgar Hoover. And where the film is most interesting is its ethnic component: Hoover, in Berlinger’s telling, was so intent on the national Italian mob that he gave a pass to Bulger’s comparatively small-scale Irish-mob misdeeds in Boston. It’s a sensational charge; but, again, he can’t prove it. The sources are mostly dead; the public records aren’t there; and Whitey becomes one of those speculative, comprehensive, well-intentioned dead-ends that would’ve been better served by a fictional treatment—maybe even an opera.

Berlinger gets Bulger on the phone (via his lawyer), an exclusive. We meet the families of Bulger’s victims, still traumatized by decades-old crimes. And Berlinger gets the current federal prosecutors—but not the FBI—to talk frankly about their case; if there are any heroes here, it’s these guys. Whitey skips Bulger’s California years entirely, and we never get a clear personal sense of this sociopath who preyed on his own community for so long, then lived in quiet, happy retirement with his girlfriend.

Whitey is an admirable and thorough effort by an outsider to comprehend this blight upon clannish Southie, a betrayal by one of its sons. If the film falls short on final answers, it hints at a pervasive, fatalistic Catholicism that—along with some sector of the FBI—enabled Bulger for so long. “I guess there’s a reason for everything,” says Patricia Donahue, whose husband Bulger shot in the head in 1982. No, there’s not. But it’s reassuring to think that way, like lighting a candle in church. Brian Miller

PWitching and Bitching

Runs Fri., July 18–Thurs., July 24 at SIFF Cinema Uptown. Not rated. 110 minutes.

This is the kind of comedy where a divorced father—covered in gold body paint, lugging a giant cross (with a shotgun inside) while portraying Christ at a street fair—brings his 10-year-old son along for a jewelry store robbery. Is this appropriate? Cowering on the floor, the store’s customers debate the question along gender lines. The women say no. The sympathetic men say, essentially, Christ loves his son, there are no good jobs in this economy, and a guy feels emasculated by the demands of alimony and hectoring exes. After a police shootout—SpongeBob Squarepants goes down!—the same complaints continue in a hijacked cab: Women expect too much in bed; there’s too much pressure on a guy to perform sexually; and men have become essentially disposable, powerless.

It’s an old complaint, rooted in the folklore of pre-Christian Europe; and it’s into such a pagan redoubt that our fugitives flee from Madrid. In a Basque village forgotten by time, three women hold sway—a matriarchal coven of witches led by Graciana (Carmen Maura, gleefully displaying all her Almodovarian expertise). She’s got an old-crone mother and a sexy daughter named Eva (Carolina Bang), and they easily overpower the hapless criminals. Up against supernatural forces, the guys are like Abbott and Costello in a monster movie, or The Three Stooges versus vampires—woefully and hilariously mismatched. Body paint removed, Jose (Hugo Silva) tries to protect his son and fellow robbers, but they don’t stand a chance against these literal maneaters . . . unless, of course, Eva takes a different kind of carnal interest in Jose.

Originally titled Las Brujas de Zugarramurdi, Witching and Bitching is the latest romp from Alex de la Iglesia, whose The Last Circus and 800 Bullets previously played during SIFF. Those unfamiliar with his earlier works will find the tone here to be the Brothers Grimm meet John Waters. Yet for all the zany laughs, de la Iglesia gives Graciana a serious agenda at the film’s final subterranean witch convention (attended by a giant, naked female ogre—her pendulous breasts as big as Fiats): The witches just want to reclaim the power taken from them by Christendom. Men have ruled for 2,000 years, and someone has to clean up their mess. Brian Miller

E

film@seattleweekly.com