Opening ThisWeek

About Alex

Runs Fri., Aug. 8–Thurs., Aug. 14 at Sundance CInemas. Rated R. 96 minutes.

Suicide attempt. Six college friends, not yet 30, converge for the weekend at a ramshackle country home. Oldies soundtrack. Generational angst. Can you guess the decade or the movie? The Big Chill comes first to mind, and there’s even a Big Chill joke or two in this stale debut feature from Jesse Zwick, son of 30-something co-creator Ed Zwick, who rose to Hollywood prominence from Glory through The Last Samurai. The younger Zwick went to Harvard and Yale, and he’s more the product of cosseted MFA-land, not the brutal TV trenches where a writer is told, If your script’s not good enough, look for another job.

The script for About Alex isn’t good enough, the direction no better. The setup is a C-plus senior thesis of a stage play (motivating incident, confined characters, past sexual intrigue, blocked writer, secret pregnancy, etc.), and none of the typical characters ever comes to life. Aubrey Plaza is a discontented lawyer; Max Mingella is a dorky hedge-fund king; and everyone else likewise registers as a cliche. Why are these people still friends? There’s topical talk of Facebook and Instagram; the resident cynic (canned, insufferably written) is shamed into admitting he watched Friends ; but this circle of friends is held together only by screenwriting contrivance, not conviction.

The writer who’s black never mentions race. The actor who’s clearly gay turns out to be straight. There’s a cute stray dog and even a car crash (bloodless, of course), but Zwick doesn’t deviate from the playwright’s dusty old rulebook. Every conflict must be resolved. Every past hurt must be forgiven. Then everyone drives home, instantly forgetting what the whole fraught weekend was about, as do we. Maybe they’ll read the status updates later. As we won’t. Brian Miller

Burkholder

Opens Fri., Aug. 8 at SIFF Cinema Uptown. Not rated. 81 minutes.

When a feature’s title is the name of one of its actors, not his character’s name, you know the project is about more than its script. Taylor Guterson, son of novelist David Guterson, scored a hit at SIFF ’11 with the likable Old Goats, starring three geezers from Bainbridge Island whom he’d roped into making their acting debuts. Burkholder is essentially the sequel, which reconvenes its principal cast—mortality tugging ever more insistently at their sleeves. Pushing 90, Teddy (Bob Burkholder) is the long-time tenant and de facto BFF of Barry (Britt Crossley), long-divorced and equally indignant about enforced bachelorhood. Teddy’s libido is more intact, even as his wits are declining. “I should do things while I still can,” he declares—chiefly photography and courting widows, neither with much success.

Also returning from Old Goats is David Vanderwal (the best actor of the three), playing an inept and equally lonely New Age vision-quest leader who takes our main duo on a forest debacle. That this excursion comes at the movie’s midpoint hints at its gentle pacing; very, very little happens in Burkholder apart from discussion about, and evidence of, our inevitable decline. The film becomes almost a documentary about the perilous making of a movie. You sense the pressures weighing upon the young director of a fragile cast, the pathos of an actor portraying his character’s—and his own—future mental decline. Each scene could be a final scene for its stars. Burkholder never becomes lachrymose about the yawning grave, and it doesn’t force any profundity upon these three men shuffling against the clock. “Let’s make each day count,” says Barry. Even if that means only a photo excursion to Cle Elum, the wheels of Teddy’s walker etched into the warm snow, it’s better than the easy chair—or the coffin. Brian Miller

Double Play: James Benning

and Richard Linklater

Runs Fri., Aug. 8–Thurs., Aug. 14 at Northwest Film Forum. Not rated. 70 minutes.

Watching two film directors play catch is not a guarantee of interest. Put Brett Ratner and Jean-Luc Godard in a field with a couple of mitts and a baseball, and things could get ugly fast. But when the players are Richard Linklater and James Benning, the back-and-forth tossing becomes contemplative, a spur to ideas, and a salute to the value of getting in a good groove. Plus, both men have baseball in their blood—they both went to college on baseball scholarships, and have made films on the sport—so they actually know what they’re doing.

The simplicity of such a sequence fits the mood of this documentary by film critic Gabe Klinger. The film tracks a few days in Texas, as septuagenarian Benning comes to Austin for a tribute headed by Linklater. The two have known each other a long time; as Linklater says in an onstage introduction, Benning was the first filmmaker invited to visit the Austin Film Society (Linklater was one of the founders) in the late 1980s. Linklater would go on to make Slacker, Dazed and Confused, and School of Rock, but at that time he was a movie-mad film fan fascinated by Benning’s experimental work. Klinger shows clips from both filmmakers’ careers, including snippets of Benning’s long-take projects (13 Lakes, for example, composed of 10-minute unmoving shots of lake and sky).

In their conversations onstage and off—they hang around Linklater’s ranch for part of the visit—there’s some implied tension between their choices: Benning has maintained a monklike devotion to his non-narrative aesthetic, while Linklater glides between his own indie projects and Hollywood. One of the best sequences, not surprisingly, has the two men looking at scenes from Linklater’s current hit Boyhood (then in the editing stage). Both artists are obsessed with time’s effect on film, and the conversation here is a real meeting of minds. One comes away wanting to see more of Benning’s world outside film, such as his painted copies of other people’s work or the two cabins he built on his property in the Sierra Nevadas—replicas of Thoreau’s Walden house and Ted Kaczynski’s Unabomber shack. Benning may be opposed to telling conventional stories, but there’s got to be a story there. Robert Horton

Elena

Runs Fri., Aug. 8–Thurs., Aug. 14 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 80 minutes.

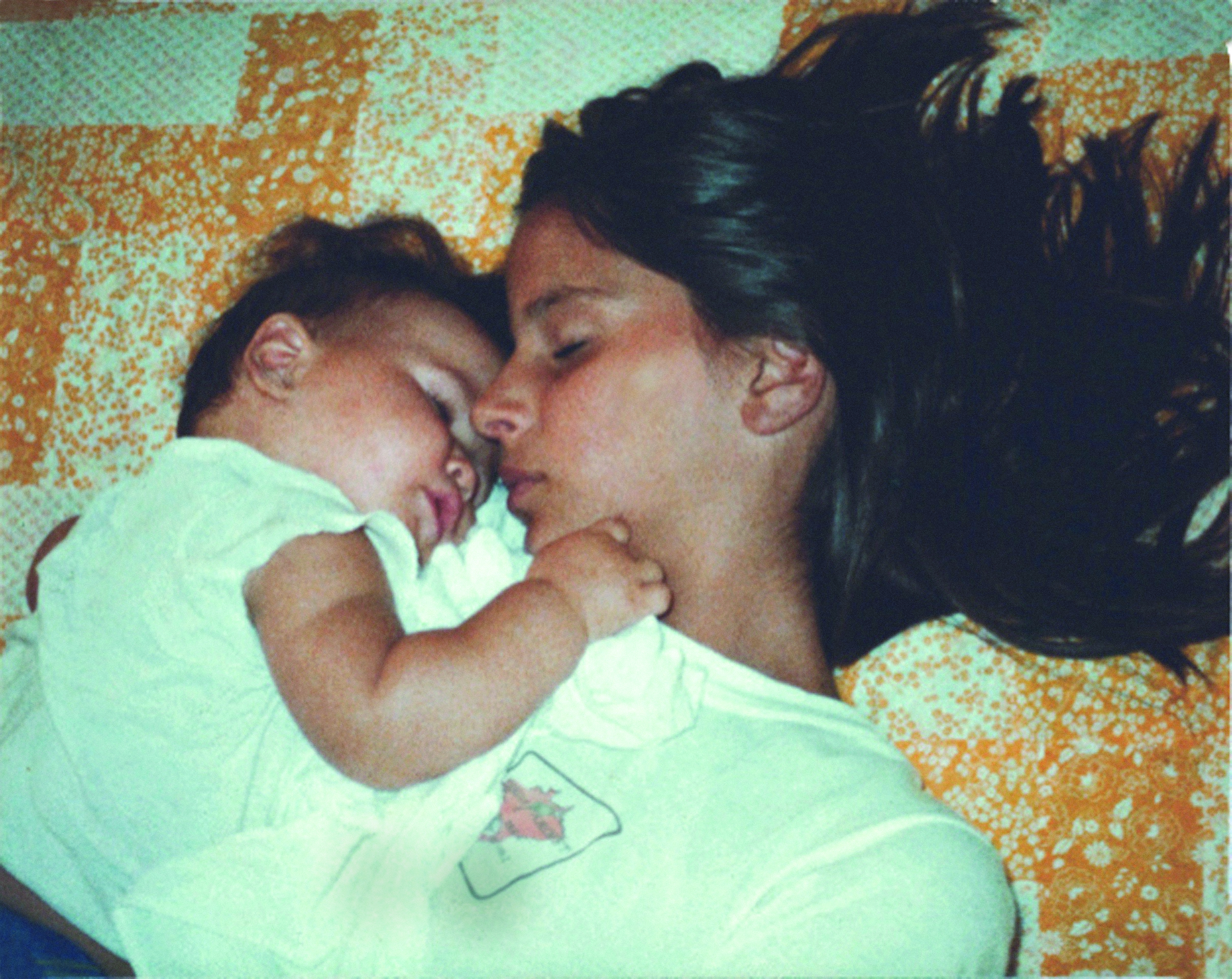

Petra Costa’s very personal documentary is about her sister Elena, 13 years older, who during the late ’80s left Brazil to become an actress in New York. Costa was then a child, with limited understanding of her sister’s motives and mental state following the move. Eventually and unsurprisingly, Costa later becomes an actress herself, then sets out to make a dreamy, elliptical film about Elena’s fate in a strange, uncaring city. Costa narrates the movie in English, though the doc is somewhat vague about her family’s educated, privileged background and the chronology of events.

The greatest mystery any of us are likely to encounter in life is that of our own family: How did it form, what are its secrets, where are its hidden-in-plain-sight tragedies and betrayals? Sarah Polley made her remarkable Stories We Tell about her uncertain parentage—an enigma that was gradually, artfully resolved. Costa, in her first film, has much less experience behind or in front of the camera. She retraces Elena’s unhappy steps, shares old home movies and family photos, plays us audio postcards from her sister, then runs out of filmmaking ideas after the movie’s big revelation at its midpoint.

“My fear is that I’d follow in your steps,” says Costa to her sister. “I drown in you.” That close identification and the film’s shadowy reenactments—Costa wandering through a blurry, wide-aperture Manhattan—are a bit much: genuine, affecting, and somewhat self-indulgent. Costa goes overboard with the Ophelia imagery in this lyrical, unconventional documentary, which is essentially an oblique essay on grief and loss. Still, whatever its shortcomings, Elena is unquestionably made out of love. Anyone who’s ever tried to understand a distant sibling will share in Costa’s heart-clenching incomprehension of a sister’s final act. Brian Miller

PHappy Christmas

Opens Fri., Aug. 8 at Varsity. Rated R. 82 minutes.

I think of Joe Swanberg’s latest lo-fi indie comedy as less a successful movie than a successful situation that happens to take place in a movie. I like it, maybe more than his prolific progression from mumblecore to auteur-dom (Hannah Takes the Stairs, Drinking Buddies, etc.), but I increasingly doubt he’ll mature into a filmmaker who can tell complete stories. Or maybe that’s an obsolete notion in the age of Twitter, like talking about the Great American Novel. You get the sense that no one here is aiming that high. Happy Christmas is a genial but very low-stakes enterprise, where you can guess the last scene by the time the first scene’s done (and not much separates the two).

Anna Kendrick, cast against her brainy, high-strung type (Rocket Science, Up in the Air) plays Jenny, a directionless and self-destructive 27-year-old who crashes at the Chicago homestead of her older brother. Jeff (Swanberg) and his wife Kelly (Melanie Lynskey) have a toddler (played by Swanberg’s own son, a wildly charismatic 2-year-old named Jude). The fun, or at least spontaneity, has gone out of this exhausted household. Jenny is the needy, disruptive force, a pothead and binge drinker, who’ll shake things up. Funny and dry, Lena Dunham is her comparatively restrained wingwoman, Carson.

All these characters, genius Jude excepted, are operating well below potential, with Jenny the queen of the slackers. She tries to enlist Kelly, a frustrated novelist, into co-authoring a trashy romance novel, leading them into a long meandering talk about sexual euphemisms with Carson. Swanberg has a generous approach to such ordinary life fodder; the millennial-generation anxiety he gets right, but he never sharpens the writing to conclusive punch lines or plot points. (The cast actually improvised much of the script.) During the summer doldrums, that’s a relief from Hercules or The Expendables 3, where everything moves mechanically forward to the next scene (or explosion). Happy Christmas can’t be bothered with that. It’s too relaxed for its own good, too unambitious, yet it still leaves you smiling in the end. Brian Miller

The Hundred-Foot Journey

Opens Fri., Aug. 8 at Ark Lodge and other theaters. Rated PG. 122 minutes.

If you were working from a menu of “crowd-pleasing movie conventions,” you could do worse than to mark these boxes: the South of France, food, Indian culture, Helen Mirren. Mix with a generous amount of sugar and a brief nod to social concern, and you’ll have a surefire profit machine that goes by the title The Hundred-Foot Journey.

To be sure, this film doesn’t stumble into its formula by mere calculation. There’s a great deal of expertise involved: Director Lasse Hallstrom (Chocolat, The Cider House Rules, etc.) knows how to keep things tidy, and screenwriter Steven Knight has the fine Eastern Promises and Dirty Pretty Things to his credit. Two of the film’s producers are named Steven Spielberg and Oprah Winfrey; last time I checked, their grasp of what the public wants has left no one in their immediate families noticeably lacking for basic amenities. Such skill is on the screen, and Journey is pleasant product, even if it seems as premeditated as a Marvel Comics blockbuster.

The zaniness begins when the Kadam family, newly arrived in France from India, fetch up with car trouble in a small town. Restaurateurs by trade, they seize the opportunity to open an Indian place—in a spot across the street from a celebrated bastion of French haute cuisine, Le Saule Pleureur. This Michelin-starred legend is run by frosty Madame Mallory (Mirren), whose demeanor is the direct opposite of the earthy Kadam patriarch (Om Puri, a crafty old pro). It’s culinary and cultural war, but will the cooking genius of Papa’s 20-something son Hassan (Manish Dayal) be denied? Madame Mallory can recognize a chef’s innate talent by asking a prospect to cook an omelet in her presence. You can already hear the eggs breaking in Hassan’s future—the movie’s like that.

Daval is a good-looking and likable leading man, so it’s too bad he’s given an unpersuasive love story with Madame Mallory’s sous-chef, Marguerite—Charlotte Le Bon, a pretty actress who doesn’t look convinced by the love story, either; her facial expression perpetually conveys the silent question, “Are you sure this is in the script?” Mirren hits her marks, and the food is of course drooled over. In setting up its culture clash, the film is firmly on the side of the Kadams and their generous portions and against all those snooty-noses across the street. Nobody seems to realize that this airless fairy tale is made with the immaculate authority of La Saule Pleureur, not the freewheeling fun of Maison Mumbai. Robert Horton

PLiving Is Easy

With Eyes Closed

Runs Fri., Aug. 8–Thurs., Aug. 14 at SIFF Film Center. Not rated. 108 minutes.

Spain only seems to export its most beautiful movie stars to us, often via Almodovar: Antonio Banderas, Penelope Cruz, Javier Bardem, Paz Vega, etc. But then there’s the short, chubby, balding Javier Camara, who is so much more worthy of your adoration. He was the chatty nurse in Talk to Her, the nelly flight attendant in I’m So Excited, a kindly drag-queen mentor in Bad Education. And whatever the role, he communicates such a direct, warm avidity for life, an obliviousness to what others think (or judge), that you feel his arms extending off the screen to embrace you. Beautiful people don’t care about you, don’t feel your pain or isolation, but his buoyant, nerdy schoolteacher Antonio knows exactly what you’re feeling. He may not know how to express those feelings himself, but he has some help in that department: John Lennon, his hero, his idol, his god.

In 1966 Madrid, Antonio teaches his pupils English by having them recite the lyrics to “Help.” He gently chides and corrects their efforts; he confiscates the boys’ Playboy pinups (those tan lines!); and he has a secret plan for the weekend, perhaps the culmination of his life’s work. As actually happened, documented by newsreels, Lennon was then filming How I Won the War in southeast Spain. The bachelor—of course—Antonio packs up his green Fiat and heads toward the coast. En route he picks up 16-year-old runaway Juanjo (Francesc Colomer), who refuses to cut his Beatle bangs, and the slightly older Belen (Natalia de Molina), aglow with an unwanted pregnancy.

Please do not expect a lot of complications or darkness here. Antonio is emphatically a good man, who can’t resist lecturing his hitchhiking students for every kilometer of their journey. (They roll their eyes but listen politely.) The Andalusian locals they meet are mostly decent folk (jokes about dialect and region you can ignore). And when Antonio finally attempts to crash the film set, protected by armed guards, well . . . that is not a moment I am going to spoil.

This movie was written and directed by David Trueba, born three years after the events in question. It’s not a baby-boomer memory piece, but actually an evocation of the twilight years of Franco’s brutally repressive regime—its cracks beginning to show, Almodovar and other cultural bomb-throwers just around the corner. But the film is equally comedy and critique. When Juanjo confesses he might actually prefer the Kinks or the Stones, Antonio screams, “Get out of the car!” He’s serious, and his two stunned passengers are left stranded by the road. But then, wait for it, the teacher has another lesson planned. Brian Miller

Magic in the Moonlight

Opens Fri., Aug. 8 at Guild 45th, Pacific Place, and Lincoln Square. Rated PG-13. 98 minutes.

Some movie critics must secretly hope that Woody Allen dies soon—if not two decades ago—to spare us any more of his Continental nostalgia trips. He got lucky with Midnight in Paris, but he’s been at it too long. Let him retire to the Riviera, not make another movie there.

Set in the interwar period in the South of France, Magic in the Moonlight isn’t Allen’s worst picture (my vote: The Curse of the Jade Scorpion), but it’s close. Colin Firth plays a cynical magician, who keeps repeating Allen’s dull ideas over and over and fucking over again. Emma Stone, in her first career misstep (Allen’s fault, not hers), plays a shyster mentalist seeking to dupe a rich family out of its fortune (chiefly by marrying its gullible, ukulele-playing son, Hamish Linklater). The recreations of this posh ’20s milieu seem curiously literal, like magazine spreads, so soon after seeing Wes Anderson’s smartly inflected period detail in The Grand Budapest Hotel, which both revered and ridiculed the past.

Allen famously started in showbiz as a magician, then transitioned to writing jokes as a teen prodigy in the ’50s. Brooklyn and Broadway are where his heart resides. Magic in the Moonlight is more like his re-rendering of a thin prewar British stage comedy he saw at a matinee during his youth, now peppered with references to Nietzsche and atheism. It’s dated, then updated, which only seems to date it the more.

Period aside, no one wants to see Firth, 53, and Stone, 25, as a couple. The math doesn’t work. It’s icky. Yet no one is in a position to tell Allen this; and every European mayor seems willing to extend him tax credits for his productions because of the local jobs and tourist bounce they supposedly provide. No less than Michael Bay and the Transformers franchise, albeit on a smaller scale, Allen has figured out how to reliably profit from making mediocre movies annually. His idol, Ingmar Bergman, retired at 86. So that means we have only seven more years and movies to expect from Allen? I wish him the best of health. But that pool chair—with Mediterranean views, no less—looks awfully comfortable right now. Brian Miller

What If

Opens Fri., Aug. 8 at Meridian and Lincoln Square. Rated PG-13. 97 minutes.

The underlying subject of many romantic comedies is chemistry, the mysterious rapport that draws people together despite whatever circumstances—being already married, having different sexual orientations—might be working against them. It’s a tough thing to simulate in movies because, well, that’s the nature of chemistry. So What If has a sizable gift in the casting of Daniel Radcliffe and Zoe Kazan, who either have terrific chemistry together or are able to fake it expertly.

In the opening scene, their characters, Wallace and Chantry, bond over refrigerator magnets at a party and he walks her home. She mentions her boyfriend at the usual moment for such things, and that becomes the major impediment to a quick resolution of this mutual-attraction club. They are in Toronto, which actually plays Toronto here, not an unnamed U.S. city. Chantry is an animator, which unfortunately means there are cartoon episodes in the film; longtime beau Ben (Rafe Spall) is about to depart for a six-month work contract in Dublin. Wallace is working a dull job after dropping out of med school because he caught his girlfriend cheating; now he’s living with pal Allan (Adam Driver, from Girls), whose new affair with Nicole (Mackenzie Davis) isn’t helping Wallace’s mood.

Elan Mastai’s script—based on a Canadian play—depends on keeping the two leads apart, which can be a labored ploy (one third-act delaying tactic isn’t remotely credible), but can also result in the occasional When Harry Met Sally rom-com success. If you can roll with said ploy, you will notice that the wisecracking zingers and cascading conversations rarely pause, and that when a quiet moment is required—a pause in the moonlight before deciding to skinny-dip, for instance—the film can handle it.

The cast is crammed with people who can deliver dialogue. Driver is consistently droll, and Megan Park delivers sidekick laughs as Chantry’s sister, who would not be averse to a fling with Wallace if Chantry isn’t going to act. Radcliffe makes his somewhat pinched charm work nicely here, if there were still any doubt that he’s quite capable outside the Harry Potter universe. Kazan, late of Ruby Sparks, continues to impress, not least because she gives a very amusing physical performance. Director Michael Dowse’s previous film was Goon, a funny hockey picture, which suggests his Canadian corner is a lively place to make movies right now. Robert Horton

E

film@seattleweekly.com