The timelessness of the issue Beethoven explored in his Fidelio—freedom vs. authoritarianism—both invites updating and renders it unnecessary. (If you can watch this opera, regardless of when it’s set, without recognizing the parallels to the realities of your time, you probably shouldn’t be allowed to cross the street alone.) Beethoven apparently intended 16th-century Spain as the setting; Seattle Opera opts for today, nowhere. Of course, for some artworks, emphasizing their universality strengthens their message, but my quibble with SO’s production, which opened Saturday, is that it doesn’t go far enough. The riot-geared cops, surveillance screens, and chain-link fencing here are just decor, whereas specificity—taking the audience into a more vividly imagined and rendered dystopia—would’ve deepened the impact.

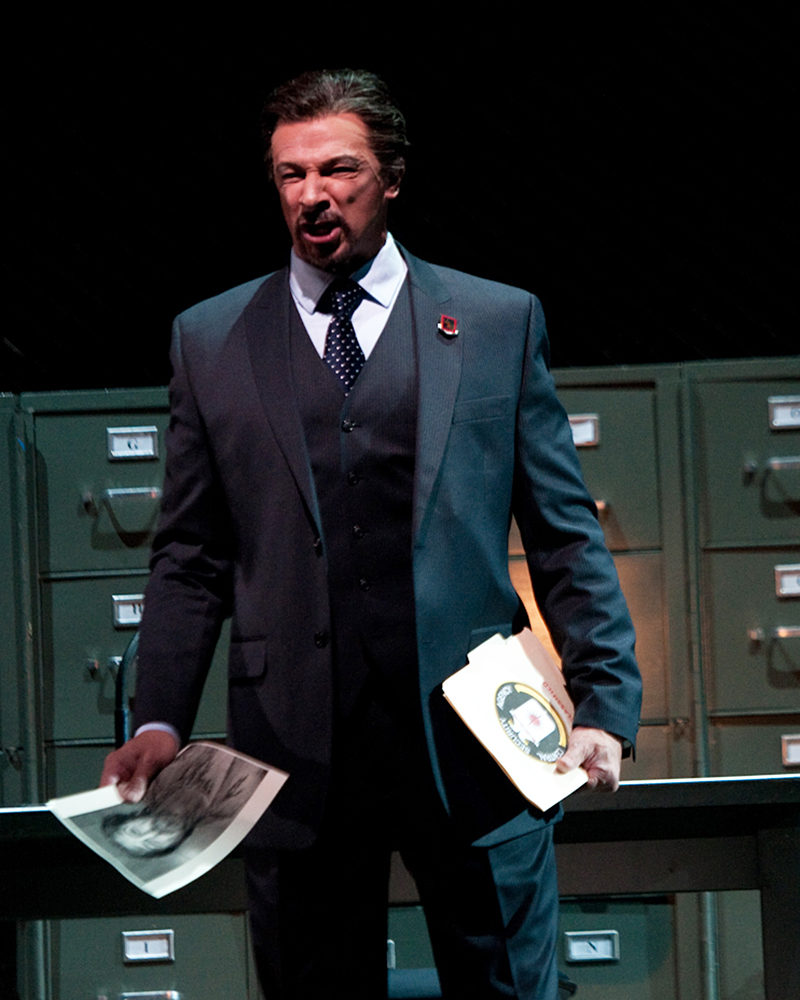

The oppressed party here is Florestan, imprisoned by his enemy Pizarro. To the relatively brief but emotionally and physically draining part, Clifton Forbis brings a brilliant, plangent tenor, which cuts the air like a steel arrow. His wife Leonore, disguised as the male “Fidelio,” finds work at the prison in order to spring him; Christiane Libor’s defining moment was her Act 1 aria, in which she heroically holds her own against the three solo horns in the orchestra that seem to want to encircle and dominate her. The libretto really stacks the deck against Pizarro, giving him not even an atom of redeeming quality. All that prevents Greer Grimsley from being ideal in the role is that he’s simply so much fun to watch and listen to, with a textured, enveloping voice you want to reach out and touch. He’s arguably too charismatic—unlike Richard Paul Fink’s chilling Pizarro in SO’s 2003 production, who was a real worm. Shedding new light on Fidelio is Arthur Woodley as Rocco, the jailer—the one character who becomes a different person by the end of the opera. Woodley makes Rocco’s moral awakening and gradual rebellion against injustice more compelling than anyone else I’ve seen in the role.

The libretto provides the laziest possible dénouement—a new character just pops up and proclaims everyone freed. Mission accomplished! (The moral: Absolute power is no problem as long as you’re not a dick about it.) Nevertheless, the stageful of choristers and extras that director Chris Alexander musters for this scene, released prisoners reunited with their families, makes for a tremendously moving finale. Conductor Asher Fisch, as always, makes the Seattle Symphony sound fantastic. Even with Beethoven’s comparatively small orchestra, the music explodes from the pit and fills the hall.