“Heroism, it would seem,” quoth Neil LaBute in his prologue to Fat Pig, “is a tough gig.” Will we stand up, against social pressure, to support a lover who doesn’t meet magazine-cover standards of beauty? LaBute’s 2004 play, second in a triad of works about non-PC sexual politics, forces us to consider whether we’re brave enough to date across the weight divide.

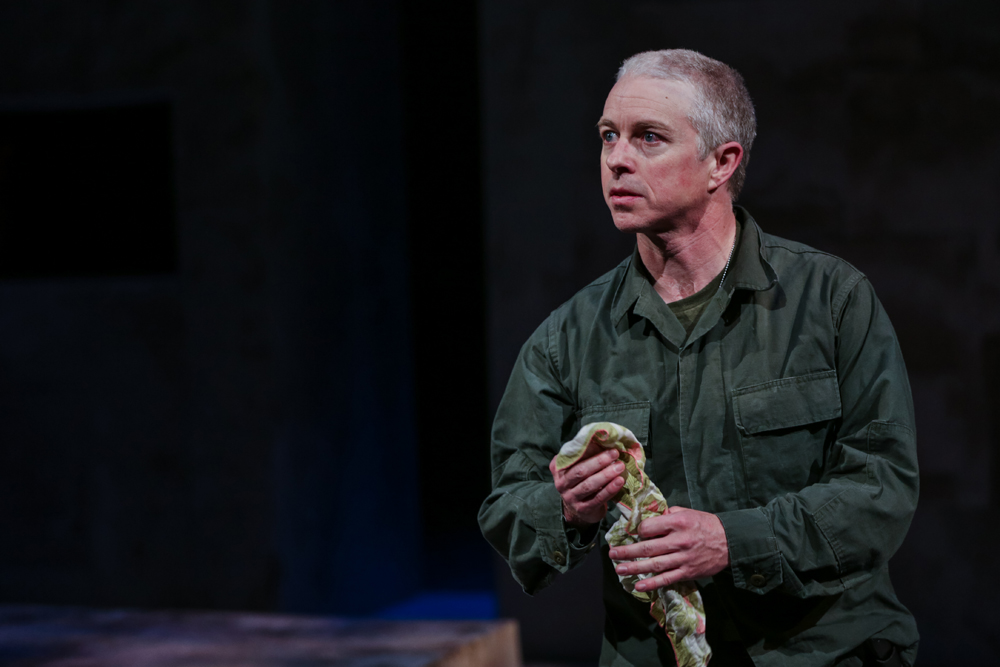

Helen (Rachel Permann), a likable gal of substantial girth, is having a nervy day when she invites trim, attractive Tom (Martyn G. Krouse) to sit with her at a crowded food court. Relieved to have a place to land with his tray of salad, Tom accepts, and soon they’re happily flirting. Yet both have their defenses: Helen a self-denigrating humor, and Tom a certain evasiveness hinting at moral cowardice. This is particularly apparent around his office buddy Carter (Justin Lockwood, the show’s director), a treacherous jerk who pries information out of Tom, then seeds it among spiteful, taunting colleagues.

The performances here are compelling and brave. Krouse’s Tom shows submissiveness from the initial scene, his uneasy blue eyes alternately apologizing to Helen and surrendering to his vengeful so-called friends. Permann nicely captures the nervous hilarity of an overfed, under-loved, and suddenly smitten woman. Helen’s babbling and second-guessing of herself gradually give way to a quiet confidence that proves irresistible to weak-willed Tom. Their romance is sweet and believable, even as Tom’s fears rise like a chilly tide around them.

Like so many villains you love to hate, Carter is the most outrageously quotable figure onstage. (“[Noah] didn’t pair up the apes with the antelope, right?…Run with your own kind.”) But in warning Tom against social ridicule, Carter’s own shame spills out—along with what seemed to be tears, but might’ve been sweat—as he recalls his overweight mother. Even so, he derides obesity like a pathogen, afraid it might contaminate him. (Playwright LaBute has himself been candid about his own weight struggles.)

This Art Attack production keeps the emphasis where it belongs, and the small cast occupies a long, narrow set with the audience seated close on both sides. Uncomfortably close, as we should be. In one lovely scene, this “mixed” couple cuddles on a sofa in an empty living room. She’s eager to get out and socialize, but he’s terrified to be seen with her. The dynamic is repeated in the moving final scene on a beach blanket that’s as lonely as a desert island—and as hot, with the lights burning to a blistering red.